Rural reality of India's 26 rupee a day poverty line

- Published

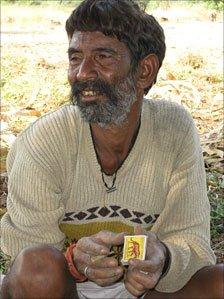

Hariya lives in one of the poorest parts of India

The Indian government recently said that anyone spending 26 rupees (51 US cents) or more a day in rural areas could not be called poor. BBC Hindi's Rajesh Joshi travelled to the central Bundelkhand region to discover the reality behind the poverty line.

Every morning, Hariya and his family climb up a rocky hill to reach their fields on the other side of the river Betua in the village of Gevra in the Lalitpur district of Uttar Pradesh.

Barefoot and hungry, Hariya's four-year old granddaughter, Shivani, and her two elder siblings also trudge along gingerly on sharp, pointy stones strewn on the path. They have no choice.

"They don't go to school. Who will look after them when they come back from school in the afternoon?" asks Hariya, 60.

His wife, son, daughter-in-law and even grandchildren work together on their three-acre land to eke out a living.

'No flour'

Hariya doesn't keep account of his total yearly expenditure, as the family has no regular source of income.

But he tells me that on average his family's total spending would be more than 26 rupees per person per day.

If that's true then Hariya doesn't fall into the category of a poor man as defined by the Planning Commission of India.

In a recent affidavit filed in the Supreme Court, the government body said that anyone spending more than 32 rupees per person per day in cities and 26 rupees in rural areas could not be called poor.

Hariya offers a warm welcome... but there is not always food

Still, there are days when Hariya's family just doesn't get enough food to go round.

"We didn't eat anything last night as there was no flour at home," says Hariya without any hint of anguish in his voice.

That explains why he didn't invite me for dinner as I prepared to sleep in a corner of his two-room shanty.

Hariya and his family gave me a warm welcome and allowed me to share their dilapidated little house. But there was no mention of food.

"It happens sometimes," says Hariya. "If there is no bread left after feeding the children, we just sleep without eating any food."

He owns land, produces food grain, but still goes hungry.

That's not the only paradox in his life. His village is electrified but it plunges into darkness after dusk.

The villagers prefer kerosene oil lamps instead of electric bulbs to light their houses because few have the cash to pay the bills.

Hariya belongs to the Saharia adivasi (aboriginal) community which has been officially categorised as Dalits, the lowest denomination in the complicated Hindu caste hierarchy - formerly known as the Untouchables.

In Bundelkhand, more than 25% of the population is Dalit. By their sheer number they became a formidable voting bloc in the state's caste-ridden politics.

They are largely considered to be supporters of Chief Minister Mayawati's Bahujan Samaj Party.

There are about 250 Saharia families in Gevra and most of them have fields beyond the faraway hills.

"Adivasis don't have the money to pay the officials - that's why we were given the land by the river. Half my land gets submerged by floods during the monsoon season," says Hariya.

Moneylenders

Bundelkhand has had a good monsoon this year but recurring drought in the previous seven years has severely damaged agricultural productivity in the region, leading to mass migration.

A report by a non-governmental organisation, Development Alternatives, says more than 15 million people have been affected by the drought.

About 40% of agricultural land has been left unattended and more than 70% of ponds and wells in the region have dried up.

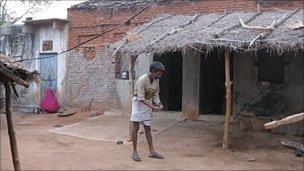

Lack of food for younger ones has led Hariya's sons to go to the cities to work as labourers

Rows of locked doors in almost every village in the region bear testimony to the farmers' desperation.

Hariya's two younger sons and their families have also left the village to work as labourers in the city.

"Once in a while they send us some money from their earnings, which we use for our daily needs," says Hariya.

Rising prices have added to his woes. He borrows from local moneylenders to buy fertilisers and fuel for the diesel pump that irrigates his fields.

"We return the money during the harvest season. For the next crop we borrow again."

This cycle of borrowing and spending keeps Hariya and his family in constant debt.

Sitting under a jamun tree on his farm, Hariya does mental calculation and tells me that seeds, fuel, fertilisers and pesticides cost him nearly 10,000 rupees (US$200) for a single crop.

Rising prices have compelled his family to cut down on essential food items from the local shop, like cooking oil, vegetables or rice.

Sometimes the family eats plain coarse bread with a pungent paste of crushed onions, chillies and salt (chutney).

Meanwhile, Hariya remains unaware of the government's definition of poverty.

For him, poverty is as hard a reality as the rocky path he walks every day to reach his fields to earn a living.

- Published5 November 2011

- Published30 September 2011

- Published21 September 2011

- Published1 April 2011