Why India is at a crucial crossroads

- Published

- comments

A society of inflating expectations is expressing frustration with democracy

For India's founders, political freedom was their great prize.

Yet decades on, what that freedom has delivered measures up poorly for many.

For India's business elites eager to compete with China, for the middle classes fed up with corruption, for radical intellectuals, for desperate citizens who have taken up arms against the state - democracy in India is a story of unravelling illusions.

Democratic politics itself has come to be seen as impeding the decisive action needed to expand economic possibilities.

In a society of swiftly inflating expectations, where old deference crumbles before youthful impatience, frustration with democracy is perhaps not surprising.

The citizenry's ire expresses perhaps instinctively something that India's government, caught in inertial routines, is in danger of missing. Societies are at their most vulnerable when things are improving - not when they are stagnant.

Sliver of time

Yet the gathering pace of history in India has made political judgement more, not less, important.

India will have only a matter of years in which to seize its chances

An India on the move cannot avoid choices.

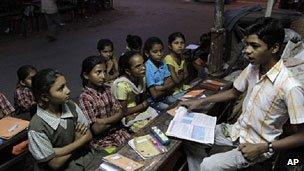

The policy choices India will need to make over the coming decade - about education, about environmental resources, about social and fiscal responsibility, about foreign relations - will propel it down tracks that will become difficult to renounce or even revise.

These choices will determine how India handles the daunting tasks it faces.

These include managing the largest-ever rural-to-urban transition under democratic conditions, and working to develop the human capital and sustain the ecological and energy resources needed for participatory economic growth.

They will also determine how ably India can contend with powerful competitor states, contain a volatile neighbourhood, and navigate a fluid international arena where capital is fly, and where new, unforeseen threats and risks are facts of life.

It's an agenda that would test any society at the best of times.

But in India's case, these tasks will have to be achieved under severe time and resource constraints.

India will have only a sliver of time, a matter of years, in which to seize its chances.

Whether it is able to do so will depend less on India's entrepreneurial brilliance or technological prowess or the cheapness of its labour, and above all on politics.

Yet, at this historical moment when emergent possibilities and new problems are crowding in, the transformative momentum of India's politics seems to have dissipated.

It's a troubling irony: political imagination, judgement and action - the capacities that first brought India into existence - seem to have deserted it.

Poisonous politics

Democracy, the distinctive source of modern India's legitimacy has, to many, become an agent of the country's ills - and drives some to put their hope in technocratic fixes.

India requires renewed political imagination to head off disaffection

Today, in many parts of the country, the identity wars that engulfed India during the 1990s - when religion and caste advanced as the basis of claims to special privileges - seem to have played themselves out.

The conventional view is that India's economic surge has stilled those fights. And although there is some truth in that explanation, it's too partial. It doesn't address, for instance, why one of India's most-developed and fast-growing states, the calendar girl of big business - Gujarat - is also the purveyor of India's most chauvinistic and poisonous politics.

In fact, what has - at least for an interval - calmed such conflicts has been the workings, however rickety, of democratic politics.

It's the capacity of India's representative democracy to articulate - and even to incite - India's diversity, to give voice to differing interests and ideas of self, rather than merely to aggregate common identities, that has saved India from the civil conflict and auto-destruction typical of so many other states.

Consider for a start the ragged history of India's regional neighbourhood: though populated by smaller and more homogenous states, their desire to impose a common identity has broken them down.

What has protected India from such a fate is not any innate Indian virtue or cultural uniqueness.

Rather, it is the outcome of a political invention, the intricate architecture of constitutional democracy established by India's founders. Democracy's singular, rather astonishing achievement has been to keep India united as a political space.

And now that space has become a vast market whose strength lies in its internal diversity and dynamism.

India must manage the largest-ever rural-to-urban transition under democratic conditions

It is that immense market, of considerable attraction to international capital, which is now India's greatest comparative advantage - and one that makes it a potential engine of the global economy.

In the years ahead, whether the old identity battles of the 1990s stay becalmed will to a large extent depend on the capacity of India's political system to sustain and spread the country's new growth.

Rising disparities - in income, wealth and opportunity - are a global fact, but they can be particularly acute in growing economies.

For 21st century India, as economic growth spreads unevenly over the landscape, the big questions will turn on the disequalising effects of economic transformation.

This is not a question that any society - democratic or despotic - has been able to solve, let alone any rapidly growing society.

The search for alternatives to market capitalism inspired the great revolutionary and reformist movements of modern history.

Sitting duck

Those movements haven't fared too well: but the living conditions that gave rise to them remain as intense and painful as ever, not least in the world's two major growth economies, China and India.

Rising disparities in income, wealth and opportunity can be acute in growing economies

Part of what it must mean, therefore, for states like India and China to take their place as major world powers, rests on their ability to invent better alternative models of market capitalism.

For India, developing such options is a priority in coming years.

It's imperative for India's economic future that the global disaffection with market capitalism doesn't take wider hold in the country. Most people in India remain hopeful that their turn will come. Yet, as events of recent weeks have reminded us, tolerance for disparities, for inequality, can shift very suddenly.

In India's case, just as six decades and more of democracy have broken down age-old structures of deference and released a new defiant energy, so too years of rapid but uneven growth may quite abruptly dismantle the intricate self-deceptions that have so far kept India's grotesque disparities protected from mass protest.

As the Indian political classes exercise their populist instincts, corporate India, heady with new opulence, lately comports itself like a well-plumed sitting duck.

Without renewed political imagination and judgement, the disaffection and alienation of those who are being left out or actively dispossessed by rapid growth could change the course of India's history.

Sunil Khilnani is Avantha Professor and Director, India Institute, King's College London, and is the author of The Idea of India, which will be published with a new introduction as a Popular Penguin in January 2012.

- Published14 November 2011