Viewpoint: Are Tibet burnings plot or policy failure?

- Published

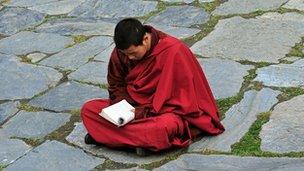

Most of the self-immolations have taken place near Kirti monastery in Sichuan

Eleven monks and nuns have set themselves on fire in ethnic Tibetan parts of Sichuan province this year. Robert Barnett of Columbia University looks at what has caused these incidents and how China is choosing to respond.

Responses to protest are basically of two kinds. The first sees protests as a stratagem or plot to damage the government. The Chinese government's handling of the self-immolations by Tibetans this year has so far been of this type, denouncing them as "terrorism in disguise" and "connected to overseas Tibet independence forces".

It responded in a similar way to protests that spread across the Tibetan plateau three years ago, and to violent protests by Uighurs in north-west China in 2009, in each case accusing exile leaders of fomenting them.

The second approach is a policy failure model, seeing protests as a response to excessive pressures placed on people by a government. Western governments that have spoken out about the self-immolations have seen them through this lens - the US urged the Chinese government to "address its counter-productive policies in Tibetan areas".

Tibetan leaders in exile took a similar view: the Dalai Lama described the "sad" and "drastic" acts as due to "some kind of policy" imposed by "hard-liner Chinese officials". The Karmapa, now a major religious leader in exile, called for the immolations to stop but described them as "a cry against... injustice and repression".

'Legal education'

What are the implications of these two approaches? The first leads to a security response. The towns where the burning protests took place have seen significant troop increases, four police stations established at the main monastery involved, and three monks given prison sentences of 10 to 13 years for allegedly helping in one suicide.

Paramilitary troops imposed blockades on two of the monasteries that saw immolations this year, in one case cutting off food and water for several weeks, and reportedly leading to the deaths of two villagers who tried to stop them entering the monastery. In April, 300 monks from one monastery were taken away for "legal education"; their whereabouts are still unclear. Such responses are counter-productive, as has already become clear.

The policy-failure approach sees itself as working by increasing international pressure on China to change its policies in Tibet. This too can be problematic, since China clearly dislikes any foreign criticism. But there is evidence that major policy change has long been needed in Tibet.

This is sometimes overstated - it is not at all correct, for example, that all areas of Tibetan culture are being targeted for annihilation by China, as some exiles claim - but it is true that some sectors of the culture and community are singled out for harassment by the state, often in ways that most Chinese would be shocked by.

This is certainly true of the monks and nuns. When I was last based at Tibet University in Lhasa six years ago, the head of our department demanded that I order my American students not to meet any monks and nuns because, she said, "they have old brains" and therefore might support Tibetan independence.

Accordingly, they were banned from entering the campus without permission, let alone our building. That policy remains in place. It is not just a form of persecution but a missed opportunity for China, given the historic contribution monks and nuns have made to Tibetan culture and education.

At that time, all Tibetan students and Tibetan government employees in Lhasa had been ordered not to have a shrine, not to practice Buddhism and not to visit a monastery. That policy was introduced in 1996, and is apparently still in place. Overshadowing all this is the government's requirement that Chinese officials and the media insult the exiled Dalai Lama in personal terms, a policy decided in 1994 and still visible in most editions of the daily papers in Tibet, and these days in Beijing as well.

'Premeditated'

In the eastern Tibetan monasteries which have seen recent immolations, the pressures have been more serious than this. Since 2006, government spending per person on security in the Tibetan areas where the immolations have occurred has been 4.5 times greater than in neighbouring non-Tibetan areas and has increased at twice the rate.

This suggests that a security build-up had begun in these areas at least a year before the first major protest occurred there in 2008, probably because they included one of the largest monasteries on the plateau.

China says it will increase financial support for monks in a bid to ease tensions

For Chinese officials, this reaction may be fuelled by frustration that another model seems not to be working. For 30 years, money has been poured into minority areas to build their economies and staunch unrest, following the theory, common in the West as well, that modernisation reduces religious faith and local identity. Instead, the opposite has happened.

The conspiracy approach to protests attempts to explain them without addressing the failure of the underlying modernisation model.

But in fact, there is one piece of evidence that one protest was planned: the Chinese government arrested two Tibetan monks in August for sending photographs to an exile of a fellow monk three days before he set himself on fire, thus "proving that the self-immolation was premeditated", according to Xinhua, China's official news agency.

But no other evidence of a plan has been produced by the Chinese government, except remarks saying that suicide is against Buddhist principles. It is true that political self-immolation was unheard of in Tibet before 2009, and that Buddhism considers suicide to be exceptionally harmful to the individual.

But like most religions, it equally regards self-sacrifice for the collective good as the highest form of virtue. The most famous of all the stories about the Buddha in his previous lives, known as stag mo lus 'byin in Tibetan, describes him lying down before a dying lioness so that she can eat his body and nurse her cubs. And, sadly, suicide as a result of intolerable policies has been common in Tibet in recent decades. What has changed this year is that political suicides in Tibet are now carried out in public.

Funds for monks

But in the complex world of Chinese politics, the decision by the government not to produce more evidence of a conspiracy might indicate a quiet shift in their approach.

Perhaps the leaders just want to avoid drawing more attention inside China to these terrible deaths, which have triggered a tide of anguished outrage among other Tibetans in Tibet, judging from coded poems and comments appearing on the internet. But they may also be starting to look at policy issues.

The signs are small and ambiguous, but interesting. Last month, a Chinese scholar, a former senior official, told a meeting in New York that the immolations have "underlying causes and we must study them seriously".

In late October, a government office in Tibet was reportedly demolished by a bomb, but no report appeared in the Chinese press, usually all too eager to link Tibetans to violence or terrorism.

In August, a new Chinese leader was appointed in Tibet who has a background in economics rather than in "handling" minorities, and he has been well received for making sure that all of this year's university graduates in Tibet were given jobs.

And this week he announced that "pension, medical insurance and the minimum living allowances" will be covered for monks at every monastery.

It is far too early to tell if this is a shift to a model that acknowledges policy failure or a return to modernisation theory - throwing state funds at a cultural and political crisis in the belief that wealth replaces religion and nationality.

Either way, given the decades-long deterioration of state-society relations in Tibet, China's leaders will have to decide whether to treat protests and suicides as conspiracies or as signs that fundamental policies need to be reviewed.

Robert Barnett is the Director of the Modern Tibetan Studies Program and an Adjunct Professor at Columbia University, New York.

- Published14 November 2011

- Published7 November 2011

- Published3 November 2011

- Published3 November 2011

- Published4 October 2011

- Published15 August 2011