Pandas under pressure

- Published

- comments

Two giant panda bears are preparing to make the long journey from China to a new home in Scotland. It will be the first time in nearly 20 years that any zoo in the UK has had pandas, and is part of the programme to preserve this critically endangered species. I was given special access to Panda Conservation Centre near Ya'an in Sichuan, where experts are working to save the bears from extinction. Here's what I found:

Yang Guang will be heading for Scotland with prospective partner Tian Tian soon

High up in the mountains of Sichuan, Tian Tian the panda is lying on her side, her chin resting on one paw, lazily staring into the middle distance. With one foot she is idly scratching her leg, looking incredibly relaxed.

Tian Tian's keepers pass her long fronds of green bamboo. You can hear her crunching them in her teeth as she munches her way through the branches.

Her name is perhaps best translated as "Sweetie". Life, it has to be said, is pretty easy for Tian Tian.

Born in 2003 in captivity, her home is the China Conservation and Research Centre for the Giant Panda on top of a mist-clad mountain at Bifengxia near Ya'an.

Tian Tian is one of the two pandas about to be shipped to Edinburgh Zoo. The hope is she will prove a big draw for the zoo when she gets there along with her mate. The zoo believes visitor numbers will double.

"Our wish is that the two pandas will be happy and healthy in Britain and produce babies," says Wei Ming, the deputy head of Bifengxia's animal administration department, a small, rotund man who clearly has a soft spot for his pandas.

Wei Ming says the pandas need to be happy to reproduce

The bears are one of the most endangered species in the world. They are not much good at reproducing naturally. The female is only fertile for one day a year, and they are notoriously choosy about who they pair off with. There's no guarantee Tian Tian will warm to her partner.

"They must like each other so that when they come into season there's a mutual attraction, that's the key," explains Mr Wei. "If one is not attracted to the other, they will just walk away from each other and nothing will happen."

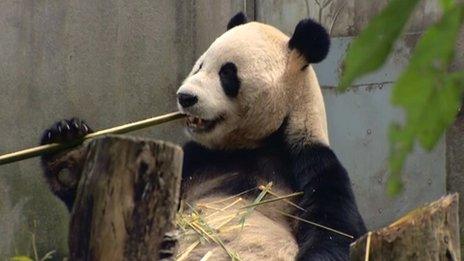

In the next door enclosure is Yang Guang, the male. He is leaning back against a concrete wall, with a six-foot-long piece of bamboo in one paw.

He grips it, chewing on the end, spitting out the splinters which pile up on his large, white furry stomach. He too is looking pretty unconcerned about anything.

Yang Guang, though, has a bit of a grumpy streak. When he sees our camera he gets up and retreats to his room where he climbs onto his bed and lies back, arms folded on his chest, staring at the ceiling, refusing to come out.

Adult pandas, you soon realise when you watch them, don't really do very much apart from chew bamboo and snooze. But that doesn't stop the visitors from warming to the animals.

"There are so many adorable things about them, like they are lazy, and totally cuddly and cute, just some very human attributes that people can relate to," says Nuo Lai. He was born in China but now lives in London, and has travelled all the way to Sichuan to see the pandas.

"The preservation of the panda is a global problem," he says. "It's kind of a symbol of a global problem. We are losing more and more species, and that has to be tackled on a global basis."

Habitat fears

The last time there were pandas in the UK was 17 years ago at London Zoo. Tian Tian and Yang Guang don't come cheap. Edinburgh is going to have to pay about a million dollars a year for the two animals.

The money is meant to go into conservation in China. The zoo will also have to pay $100,000 a year for bamboo to keep the two pandas fed.

It's thought there are only around 1,800 pandas left alive; an estimated 1,500 still in the wild, the rest in research centres and zoos.

Breeding them in captivity has proved successful thanks, largely, to the use of artificial insemination. In China the numbers have gone up from 200 in captivity three years ago to 300 today.

But in their natural habitat the bears are increasingly under pressure. The mountains of Sichuan where pandas live are picture-postcard perfect, jagged snow-covered peaks, alpine forests cladding the hillsides all the way down to blue glacial lakes.

Traditional panda habitat like this park in Sichuan has been hit by development and tourism

Jiuzhaigou National Park in northern Sichuan was created around 30 years ago to help preserve the panda. The park, with its mountain scenery, has become one of Sichuan's most popular tourist attractions.

Foaming water cascades down waterfalls. A spray of fine mist hangs in the air in the forests. Groups of Chinese tourists snap pictures of themselves in front of the falls.

"Jiuzhaigou is famous in China," says Yao Caiyun, one of the visitors. "We've always wanted to come here. It's truly beautiful. It's like walking inside a picture, at every turn it is like a painting."

Despite its remote location Jiuzhaigou is one of China's most popular national parks, drawing two and a half million visitors a year. Buses ply the roads ferrying the tourists from one spot to another.

Crowds gather at the most scenic sites. It's even become a favourite location for couples to take wedding photos, so women in ornate wedding dresses and their smartly-dressed husbands-to-be pose in front of the scenery.

"Nowadays Chinese people are getting richer, we're starting to travel," says Mr Su, another of the visitors. "That's why wherever there's nice scenery there are always lots of people. To find somewhere with no tourists you have to climb a mountain, otherwise its overcrowded."

Today there are no pandas left in Jiuzhaigou. The bamboo they eat flowered and then died back a bit more than a decade ago. It's part of the bamboo's natural lifecycle, but it leaves the pandas vulnerable. Then visitor numbers to the park surged. The pandas have died or moved away.

"Pandas are known as the hermits of the forests. They don't like noisy places. People might like living in cities. But wild animals prefer quiet, peaceful places," says Professor Yin Kaipu.

Pandas like Tian Tian are solitary animals that prefer a quiet habitat

He was the man who suggested Jiuzhaigou should be made a national park. Now he thinks development has helped push the pandas out.

"Think about it, if a place is full of tourists, will pandas continue to exist there? It's not possible. The only thing they can do is migrate elsewhere," he explains.

At Jiuzhaigou they are trying to change things. It's become the first national park in China to promote ecotourism alongside mass tourism.

An Irishman, Kieran Fitzgerald, has been at the park for three years working on the plan. He's seen the speed at which China is developing and how that is impacting on even its remote places like Jiuzhaigou.

"The pace of China's modernising, the amount of car-owners, the amount of self-drive tourists we've seen this year in Jiuzhaigou, in Sichuan, that pressure puts a big strain on the environment," he says.

His aim now is to encourage more sustainable use of the park, and to try to educate visitors about the importance of preserving China's wild places. So he has opened up more remote valleys to small groups on walking and camping tours. This year there have been 400 visitors who have taken the ecotours.

"It's going to take more time before people see the value of protecting these still pristine areas, which are habitats to all these endangered species like the pandas and other species," he says.

In the meantime the constant expansion of China's roads and railways, its towns and cities, means the pandas' existing habitats are being carved up into smaller and more isolated pockets.

That's a problem because it makes it even harder for the bears to intermingle and breed. In the long term it means the only viable population left may be the one in captivity.