Burma exiles watch and wait

- Published

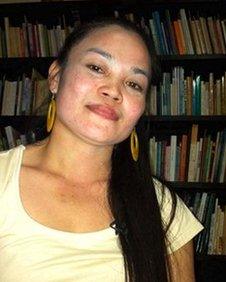

Ying fled across the border to escape persecution by the Burmese military

There has been a flurry of diplomatic visits to Burma in recent months. But none has received quite the same level of scrutiny as that of Hillary Clinton - the first US secretary of state to travel to the once ostracised South East Asian nation for half a century.

Mrs Clinton will meet government ministers and opposition figures including the Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi, and will shuttle between Burma's remote jungle capital Nay Pyi Taw and the country's main city Rangoon, in what is now becoming a well-trodden path for visiting VIPs.

The aim is to encourage the former generals now running Burma to continue to deepen the reform process that appears to be under way.

Across the border in Thailand, the sudden push for engagement with the still relatively new Burmese government is viewed with a mixture of cautious hope and wary scepticism.

In a small library in the northern Thai city of Chiang Mai, adults and children sit around a large wooden table covered in white cards with English words written on them.

The adult language students fled into exile. The children were born in exile. The Best Friend Library is a centre of learning and activism. A big, stylised poster of Aung San Suu Kyi adorns one wall. Books about Burma line the other.

Ying belongs to Burma's ethnic Shan minority. She and the man who is now her husband fled across the border more than two decades ago when Ying was still a teenager.

She recounts a catalogue of abuses committed by the Burmese military. She witnessed soldiers force her mother inside a barrel full of water, then roll it down a hill.

"I still miss my mother," she says, wiping away a tear with the back of her hand.

"Once I lost her there was nothing left for me there anymore [in Burma]. The army said if we didn't leave our home they would burn it down and burn us too. I've seen so many things. I don't think I could ever go back."

Military unbeatable?

Over the decades since independence from Britain, many of Burma's ethnic minorities have taken up arms. Ceasefires have been agreed and broken, and hundreds of thousands of civilians have fled across the border into Thailand.

Hundreds of thousands of Burmese refugees have fled across the border into Thailand in recent years

Villagers have been forcibly displaced or recruited to work as porters for the Burmese army. Human rights groups say the abuses are continuing unabated in conflict areas.

Diplomats and activists warn resolving Burma's long-running ethnic insurgencies and addressing the rights and concerns of ethnic minorities must now be a priority if reform in Burma is to succeed.

A recent meeting between a Burmese government minister and representatives from some ethnic groups in a town on the Thai-Burma border perhaps offers a tentative sign of hope.

But there is a long way to go before the years of bloodshed and mistrust begin to be overcome.

In the welcome shade of a quiet park in Chiang Mai, Aung sips an iced latte between intense bursts of conversation.

Like Ying, who fled from her Shan homeland, Aung has also witnessed violence and brutality first hand. But from the other side of the front line. He was a soldier in the Burmese army until he deserted in 2005.

Aung is convinced there can be no real freedom in Burma until there is peace but he's deeply pessimistic about the chances of that happening.

"The military won't give up easily" he says. "You can't beat them in battle and you can't beat them by protesting."

'Music to my ears'

But inside Burma, things are changing. A new parliament has enacted laws including the right to form trade unions. Some political prisoners have been released.

Aung Naing U says reformers are battling the old guard inside Burma

Some media restrictions have been eased.

Perhaps the most significant vote of confidence in the evolving transition was the recent decision by the National League for Democracy, the party led by Aung San Suu Kyi, to rejoin the official political system and to contest forthcoming by-elections.

Burma's political exiles are watching the shifting landscape carefully. After so many years of personal sacrifice and committed struggle it would be understandable if some felt doubtful that the recent reforms are for real.

But Aung Naing U is heartened by recent developments - in particular Aung San Suu Kyi's likely bid for a political seat.

"It is music to my ears," he says, standing next to a lake in the campus of Chiang Mai University where he now teaches.

Aung Naing U took part in the student uprisings in Burma in 1988. He escaped shortly afterwards and has not been back home since.

He cautions that no-one should expect Burma to be transformed overnight.

"It will be step by step because, after all, the former military men are still in power" he says.

"There are people who want to go back to the old system and of course there are many people who want to go forward, so there is also a kind of tension between the 'old timers' and the 'old timers with the new ideas'."

It is only a year since Burma went to the polls in elections widely criticised as a sham designed to perpetuate military rule in civilian guise.

Few predicted the pace of change seen in the past few months.

But the focus of attention now is not so much on how far Burma has come, but on how far its leaders are prepared to go along the road towards genuine freedom and democracy.