Philippines' Gloria Arroyo: Long legal battle looms

- Published

The government wants to prevent Gloria Arroyo from travelling overseas

If you had told Filipinos back in 2001 that their newly elected president Gloria Arroyo would one day be arrested for vote rigging, not many would have believed you.

Mrs Arroyo was ushered into power promising a new era of integrity and honesty.

To the Philippine people, she was everything that her loud hard-drinking predecessor Joseph Estrada was not.

She was quiet and studious; she had studied economics in the US as a classmate of Bill Clinton; she came from an illustrious family - her father Diosdado Macapagal was president in the 1960s.

And perhaps most importantly, even though she served as Mr Estrada's vice-president, she had publicly distanced herself from the accusations of corruption and embezzlement that had led to him being ousted from office.

But now, 10 years later, history is repeating itself and Mrs Arroyo, like Mr Estrada before her, has been arrested.

She has been charged with electoral fraud and, if found guilty, could spend the rest of her life in jail.

'Survival mode'

At the beginning of her presidency, Mrs Arroyo had some notable successes.

It was under her watch that the Philippines' burgeoning call centre industry was established, and she built much-needed roads and roll-on, roll-off ferry services between the country's many disparate islands.

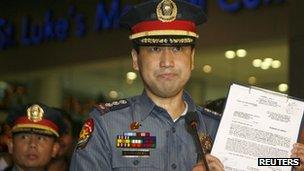

A warrant has been issued for Mrs Arroyo's arrest last month

"The ferries made a real difference in facilitating the movement of goods around the country. It was a big change for the better," says Gonzalo Jurado, Mrs Arroyo's former economics professor and one of her main supporters.

But it was not long before Mrs Arroyo found herself becoming the focus of corruption allegations.

In 2003, a group of young soldiers took over a hotel and shopping centre in central Manila, accusing Mrs Arroyo of mismanagement and allowing their generals to siphon off military funds.

The mutiny ended peacefully, but the corruption claims surfaced again the following year, when she faced her first election.

She had replaced Mr Estrada without an election being held, but in 2004 she had to fight her own campaign, which she won only narrowly.

In the aftermath of the poll, Mrs Arroyo was accused of vote-rigging, and a wiretapped recording of a conversation between her and an election official allegedly discussing her margin of victory eroded her popularity still further.

"It was in 2004 when it all started to unravel," says political analyst Marites Vitug. "Many of her allies were disappointed and deserted her, so she got into survival mode."

In the years that followed, Mrs Arroyo faced numerous other allegations. Critics say she siphoned off $16m of government funds that should have been used to buy fertiliser, and tried to enter into a broadband deal to her own personal advantage.

She denied all the claims, and clung on to power, despite several further protests and coup attempts.

But by the time her term ended in June 2010, she was the most unpopular president since Ferdinand Marcos, the man who was toppled in the People Power Revolution of 1986.

Election pledge

Once she had left office, it seemed only a matter of time before Mrs Arroyo would be charged over some of the many accusations being hurled her way.

Gloria Arroyo's opponents want to see her in court - or behind bars

Her successor, Benigno Aquino, has made tackling corruption one of the most important tasks on his agenda.

He knows that if he cannot get the woman who headed the previous administration to answer for her actions, his credibility as president will be dealt a heavy blow.

"It would make him look weak, like he's not able to fulfil his election promises," says Bernito Lim, a political science professor at Ateneo de Manila University.

But it is not proving easy. In trying to get her to face a trial, Mr Aquino and Justice Secretary Leila de Lima have found themselves on a collision course with the Supreme Court.

The court has twice overturned a government order preventing Mrs Arroyo from leaving the country.

Judges are now looking into whether the panel that issued the charges against her was unconstitutional - and even whether Mrs de Lima herself should be held in contempt of court.

At one stage, Mrs Arroyo was told by the judges that she could leave, so she arrived at the airport in a wheelchair and neck brace only to be turned away by government officials.

Filipinos watching the saga unfold on TV would be forgiven for thinking it was the plot of one of the telenovelas that are so popular throughout the country.

Analysts say there is a simple explanation for all these twists and turns: while Mr Aquino's supporters dominate Congress, Mrs Arroyo's appointees still dominate the Supreme Court.

"What they're doing is to vote in her favour," claims Marites Vitug. "It's a very cultural thing. When the appointed power puts you in a position, you owe the appointing power a debt of gratitude."

Mrs Arroyo has now been arrested but this, of course, is only the beginning. Next there is the matter of the trial. If she is found guilty, an appeal would again involve the Supreme Court.

The current charges relate to claims that Mrs Arroyo helped the powerful Ampatuan family rig an election in 2007, but both her supporters and detractors know there are likely to be more charges to come.

"It's going to be a long drawn-out battle," says Professor Lim.

Despite these hurdles, Filipinos are still keen for Mrs Arroyo to have her day in court.

Maria Ignacio, a Manila teacher, sums up the feeling of many: "I just want to know that no-one is above the law."

- Published25 November 2011

- Published8 November 2011

- Published8 December 2010

- Published30 June 2010