Held 'hostage' by China

- Published

- comments

She has described herself as China's "hostage", and her story deserves to be told widely.

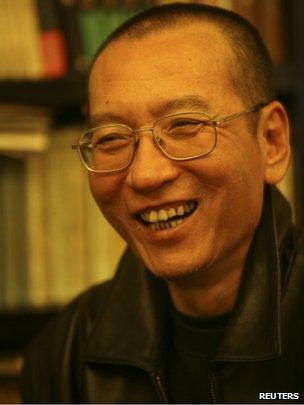

Liu Xiaobo was convicted of attempting to 'subvert' the Chinese state

For over a year now Liu Xia has been deprived of her liberty by the Chinese state, for the sole reason, it seems, that her husband won the Nobel Prize.

Liu Xia is guilty of nothing. But she is married to Liu Xiaobo, the Chinese political activist, selected by the Nobel committee last year as winner of the Peace Prize.

That, it seems, is why she has been under "house arrest" since 18 October 2010, though her detention has no discernible legal basis. It is why her case is extraordinary, and why it deserves mention now, one year on from the award of the prize.

When the Nobel committee announced the award Liu Xiaobo was already in jail. He's been there for three years, and has been convicted of attempting to "subvert" China's Communist Party-led state.

His crime was to help author and circulate Charter '08, a bold call for political reform in China. He was tried and convicted. His supporters said the process was unfair, but he at least faced a court.

His wife has committed no crime and broken no law. There don't appear to be any legal charges against her. In fact, she is said to have pleaded with her husband not to take part in drafting the charter. Still she is being held.

I met Liu Xia in Beijing a couple of years ago. A slim woman, now in her early 50s, she is a poet and painter. She looks a little like a Buddhist nun, spectacled, her hair shaven.

Shy and quiet, it's hard to see why anyone would view her as a threat. But even then she was under police surveillance and had to slip out of her home to be able to talk to us.

Cut off

China called the decision to give her husband the 2010 Peace Prize a "desecration" of the idea of peace, and an attack on China's sovereignty and its legal system, saying he was a criminal and should not be honoured.

So it was no surprise that it moved to detain Liu Xia. It was thought China wanted to prevent her travelling to Oslo to collect the award on her husband's behalf, and would quietly lift restrictions on her a few weeks later.

But, now a year on, she is still being held, we believe, in her own home. Her phone line remains cut, her internet connection shut, visitors turned away by guards posted at her compound.

For one - very brief - moment in February, Liu Xia, was, it seems, able to access a computer and have an online conversation with a friend via an instant messaging system.

The BBC saw the transcript of what appeared to be her internet chat which lasted just five minutes. In it Liu Xia said she "can't go out" as her "whole family are hostages".

She added she was "so miserable", saying "I'm crying... nobody can help me".

When the United Nations Working Group on Arbitrary Detention asked earlier this year about the restrictions on her, the Chinese government admitted that "no legal enforcement measure" had been taken against Liu Xia. It holds her anyway.

The Nobel committee said one reason for giving Liu Xiaobo the Peace Prize was that China's people had basic rights guaranteed by China's own constitution and international conventions to which China is party, but "in practice, these freedoms have proved to be distinctly curtailed for China's citizens".

The committee members added that "China's new status must entail increased responsibility".

'Persecution'

But a year on, China's critics argue that things have only got worse.

Testifying this week to the US Congressional Executive Commission on China, Li Xiaorong, a member of the campaign group Human Rights in China, attacked Beijing for what she called "the issue of systematic violation by the Chinese authorities of the Chinese law and international human rights law, as evidenced in the persecution of Liu Xiaobo and many other Chinese for exercising their freedom of expression and for engaging in peaceful activism to promote democracy and human rights".

Li Xiaorong claimed that "secret detention and enforced disappearance has been applied on multiple occasions, for example, to many activists and lawyers during the government crackdown on online calls for Tunisian-style 'Jasmine Revolution' protests last February, and to the artist Ai Weiwei".

"In February, within a few weeks, a total of 52 individuals were criminally detained, at least 24 were subjected to enforced disappearance."

China's position is that it is a country ruled by law and that due process is followed.

But Liu Xia too has disappeared from view. Its treatment of her leaves China open to the charge that it is disregarding its own laws. Its actions - locking her up in her home - can be painted by its critics as purely vindictive.

That's hardly the image China wants to paint of itself to the world. At a time when China's economic power is growing, it wants to increase its "soft power" too.

But refusing to let a soft-spoken, shy, middle-aged woman who has committed no crime even step out of her front door freely is unlikely to win China many admirers.