Selling South Korea: No 'sparkling' brand image

- Published

South Korea's image is changing as K-pop bands such as Girls' Generation get more popular

Word association games are easier with some places than others.

Japan: sushi, cherry blossom and Mount Fuji. America: hamburgers and Hollywood. Paris: romance, croissants and the Eiffel Tower.

Now try with South Korea. If you are struggling to get past economic powerhouse and computer chips, you are not alone.

South Korea's government has been trying to change the country's international image - or rather its lack of one - for years.

And even those involved - like Peter Kim, brand manager for the Seoul government - admit it has been a tough sell.

"We're among the world's 13 largest economies," he said. "But we still don't have our own unique brand."

Partly, he said, that is because for the past 50 years, South Korea has been focused on building the country, not marketing it.

But now it is starting to think about its national brand, it is facing some unique challenges.

'Two Koreas'

"It's hard, because we share the name 'Korea' with North Korea,'' said Cho Hyun-jin, from the president's foreign media team. ''And there are still many people in the world who don't even realise there are two Koreas.''

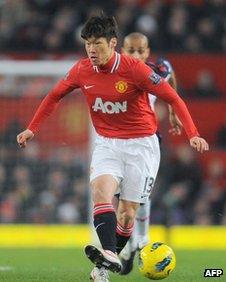

South Korean footballer Park Ji-sung is a Manchester United mid fielder

North Korea - led until last month by Kim Jong-il - is a country associated with food shortages, political repression and an ongoing nuclear weapons programme - issues that help make it a regular feature on global news channels.

"Do you know who the most famous Korean is?" one senior marketing official said gloomily over coffee one morning. "It's Kim Jong-il. That's what we're dealing with in branding this country."

But some officials, like Mr Cho, believe the country's image has been tarnished by the culture of its allies too. In particular, a popular American television drama set during the Korean War called M*A*S*H*.

"Many people think Britain has the best intelligence agency just because of James Bond," Mr Cho explained. "In M*A*S*H* Korea was portrayed as worn-down, third-world: a hopeless country."

That image was not helped by decades of violent demonstrations, coups and military dictatorship, as the country made its way to democracy.

Public makeover

Now, said Mr Cho, things have changed.

"There's been a major image shift. Now it's Samsung products, Korean pop bands, and [the Manchester United footballer] Park Ji-sung."

And there has been a public makeover to match.

Over the past few years, a flurry of marketing campaigns describing South Korea - and its capital city, Seoul - as "sparkling", "dynamic", "infinitely yours" and the "Soul of Asia" have appeared on billboards and TV channels around the world.

A new Presidential Council on Nation Branding has been created.

And the Seoul city government has ploughed in $100m (£64m) over the past few years to promote the nation's capital abroad.

But despite the extensive advertising campaigns, South Korea still seems to have a much weaker national image than many other countries, at least outside Asia.

Dr Charlotte Horlyck, a specialist in Korean art history at London's School of Oriental and African Studies, said the marketing is often unsuccessful because there is no clear message.

"There are too many conflicting images which keep changing all the time, as governments and policies change," she said. "So there's no consistent image that people conjure up in their minds when they think about Korea."

Take the slogan "Korea, Sparkling".

"It doesn't make any sense because it's not easy to interpret - what is sparkling? Is it the people? The springs? The brand has to be very easy to understand," she said.

Mr Cho agrees that there needs to be more co-ordination between South Korea's different marketing agencies.

"We need to be more selective in what we're going to sell out of Korea," he said. "And more strategic in promoting it."

'Let people decide'

In fact, branding often works best when consumers themselves decide what's iconic, said a senior marketing official at one of South Korea's most recognised international companies.

Branding work best when consumers decide what is iconic, experts say

Fiona Bae, deputy PR manager at Hyundai Capital & Hyundai Card, said people respond when they are offered access to a new culture, not told what to like about it.

Hyundai Card recently worked with New York's Museum of Modern Art to put together a collection of new Korean designers.

"What we found very interesting was that the products the MoMA people picked weren't necessarily things we would have picked,'' she said. ''That's one key thing we learned about branding Korea: let people outside Korea decide for themselves what they like.''

But according to one insider, the slogans and images for at least one recent government-funded campaign were chosen by a handful of South Korean experts - most of them male, and all of them over 40. Foreign consumers were only asked their opinion after the decision had been made, he said.

To be fair, many of South Korea's campaigns to date have been primarily about attracting tourists, for example, rather than the wider issue of national image.

And according to Simon Anholt, that is all you can hope for. Mr Anholt works as a policy advisor on these issues to national governments. National branding itself, he said, is doomed to failure from the start.

You can advertise your country to tourists, he said, but not actively 'brand' it. ''Branding is something that happens in the consumer's mind."

'Turning point'

Mr Anholt publishes a global index of national brands each year. That survey showed that people largely do not change their minds about other countries and if they do, they do so very slowly.

''National image is not created - or much affected by - the media," he said.

And yet, South Korea has gradually been creeping up his index from its original place near the bottom of the list.

"Korea's image is improving, because Korea is improving," he said. "It's getting richer and more confident."

"It's also starting to understand that reputation is something you earn, not something you construct. It's started doing things, rather than saying things," he added.

Nothing, perhaps, illustrates that theory better than the G20 summit, held in Seoul in 2010.

The Presidential Council on Nation Branding said that the summit increased awareness of South Korea by almost 17%, and "likeability" by around 3.5% - making it one of the country's most successful 'marketing' events.

"The G20 was a turning point," said Mr Cho. "Korea moved from being a follower of the international agenda to being an agenda-setter. We're part of it now."

Mr Anholt agreed. "My only criticism is that they're still constantly publicizing the fact they want a better image,'' he said.

''The first rule of propaganda is that, if you're going to do a number on people, you shouldn't warn them you're about to do it."

- Published2 January 2012

- Published3 January