Japan's damaged Fukushima nuclear plant one year on

- Published

For almost a year, it had been the focus of the fears of the Japanese people.

Now the Fukushima Daiichi plant was right up ahead, glimpsed between the pine trees that surround it through the windscreen of our bus.

We were being driven right to the plant, the first group of foreign journalists allowed in since the nuclear crisis began.

The journey had begun as it does for the 3,000 men who work there each day - those who do not sleep at the plant itself.

At J-Village - once Japan's national football training centre - we got dressed in protective gear, ready to face the radiation.

No man's land

First, a white plastic boiler suit, then plastic booties over our shoes - two layers. Two pairs of gloves and a paper surgical mask. We were also given full face respirators; we would have to put them on later.

The entrance to the exclusion zone is guarded by a police roadblock. We were waved through and out into a no-man's-land.

Weeds now grow around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant

Fields were overgrown, pavements taken over by weeds. Cars and homes stood deserted. A recent study has suggested even the birds have abandoned the area. Shops were still full of stock, the magazines in the windows of the convenience shop faded by the sun.

And every kilometre we went, the radiation levels steadily rose, the numbers announced over a loudhailer by staff from the plant's operator, Tepco.

When we reached the power station, we were ushered quickly inside the main control room building, noisy with the droning of air filters keeping the radiation out.

Inside, the walls are decorated with good-luck messages from around the world. Thousands of origami cranes festoon the stairs, a symbol of peace more usually associated with Hiroshima.

In the control room itself, someone had written the Japanese character for hope on a Rising Sun flag.

There, perhaps 100 men or more were sitting around tables working at laptops, monitoring the reactors minute by minute.

Cold shutdown

They are now in cold shutdown, the water inside below boiling point. Recently, a thermometer showed the temperature rising inside one, apparently uncontrollably, to the alarm of the Japanese people. It was tracked down to faulty instruments.

The atmosphere was calm, but intense. How different from the panic and fear described by the few who have spoken out among the workers who were there in the first days of the disaster, when in the darkness of a blackout they had to rig car batteries to the instruments to try to find out what was happening. When they heard the explosions and waited and wondered, was this death?

At the time, the people of Japan did not know quite what a razor's edge their nation was on as the reactors melted down. The prime minister at the time, Naoto Kan, has since admitted he feared he would have to order the evacuation of Tokyo.

The men became known as the Fukushima 50 - those who had saved Japan.

Those who spend their working days inside the plant circulate in full protective clothing

In a room with bunk beds set up in it, we were introduced to the plant supervisor. Takeshi Takahashi is hollow-eyed and looks and sounds exhausted.

He told us one of the big concerns is another earthquake or tsunami. Perhaps that could tip the disaster into a crisis once again.

"What we have in mind is to prevent the release of radioactive gases, the leakage outside the power station which happened before," he said.

"We want the local people to be able to return to their homes as soon as possible."

Then we were told to put on our respirators. The hoods of our boiler suits were checked to make sure there were no gaps.

We were being taken to see the reactors themselves. The journey was by bus again, a guide pointing out the giant water tanks that are being built, fields of them, to store contaminated water.

There are water pipes and power cables snaking along the sides of the roads, the cooling system keeping the reactors under control.

About 100m (330ft) or so from the reactors, the bus stopped and we were allowed to get out.

"Don't touch this handrail," said the guide. "It is very radioactive."

The reactor buildings are still skeletal, testament to the power of the explosions that shook the plant nearly a year ago.

But now giant red and white cranes loom over them. Men in white boiler suits could be seen working high up amid the wreckage.

The goal is to eventually dismantle the plant, removing the nuclear fuel. But Japan's government has warned it could take up to 40 years.

Our route away, back in the bus, took us right past the reactor buildings themselves, scarred by the power of the sea.

Letter to the children

In places, there were wrecked trucks on their roofs and sides where they were left by the tsunami.

The Fukushima 50 say they are grateful for the support and encouragement they have received

Between the reactors and the sea, a very short distance, a new sea wall of stones in big mesh bags had been built as protection in case the giant fault off Japan's coast ruptures again, triggering more waves.

And, all around the site there were men at work, directing traffic, operating mechanical diggers, driving trucks, controlling the traffic. All wearing full protective gear against the radiation all around.

Back at the J-Village, on the edge of the exclusion zone, we found out what may motivate some of these men to risk their lives in what must surely be one of the most hostile working environments on earth.

"I worked here before the disaster, so since my plant is in this condition, I think this is my mission to stay here," said Tetsushi Tarumi who had been selected to meet us.

"As for my health, my dose exposure is within the legal limit. I have no concerns about health."

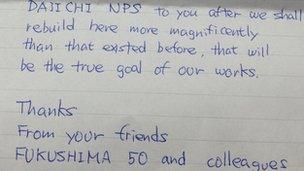

Then, as I left J-Village, a worker discreetly pressed a note into my hand. When I read it later, I saw it was addressed "To all child in the world".

"Dear our friend," it said. "First, we would greatly appreciate that you gave us much encouragement, and then we could overcome this trial with the encourage you gave.

"Fortunately, we could get the stabilisation of the plants, and the radiation level of the environment is decreasing.

"But this is not the end of our jobs.

"We shall transfer Fukushima Daiichi NPS [nuclear power station] to you after we shall rebuild here more magnificently than that existed before, that will be the true goal of our works.

"Thanks. From your friends, the Fukushima 50 and colleagues."