Nepal's long wait for war crimes justice

- Published

The fate of about 1,400 people who went missing in the war is still not known

Nepal's bloody insurgency formally ended six years ago but political stalemate has held up any efforts to investigate atrocities committed during the war. As the BBC's John Narayan Parajuli reports from Kathmandu, victims of war crimes fear the perpetrators may now go unpunished.

Nepal's civil war was long and brutal. Almost 15,000 people were killed, with thousands more tortured or injured and almost 100,000 internally displaced.

Both the army and the Maoist rebels are accused of committing atrocities during the decade-long conflict which ended in 2006.

But the fate of about 1,400 people is not known to this day - they have been categorised as "involuntarily disappeared".

Families have for years been trying to find out what happened to their loved ones, but with little success.

Justice elusive?

But political stalemate in Nepal has dampened hopes that any progress might be made on the issue.

A 601-member Constituent Assembly elected in 2008 to draft a new constitution for Nepal, but which also served as a parliament, failed to meet the May deadline.

As the country's political class grapples with the consequences of what amounts to a constitutional crisis, justice for victims of war crimes seems further away than ever.

The matter has been further complicated by a debate on whether any commission investigating war crimes should focus on prosecuting suspects or allowing them to confess in return for an amnesty - similar to the South African Truth and Reconciliation Commission set up in 1995 after the end of apartheid.

There have been some forensic investigations at suspected burial sites as part of investigations into war crimes

Most political parties favour the amnesty option, while the UN and most people who lost loved ones during the conflict favour the prosecution option.

In its report on Nepal's human rights situation in March, the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) expressed concern that political parties - by agreeing to create "transitional justice commissions" to examine alleged war crimes - were in effect putting the emphasis on reconciliation rather than prosecution.

It warned that such commissions would serve as "amnesty mechanisms", allowing an escape route for individuals accused of serious human rights violations.

The Maoist-led government in December decided not to extend the term of OHCHR's Nepal office, and since then the UN has been largely kept out of the consultation process.

Unreported cases

The move was arguably a clear sign that the killers in two notorious war-time cases - those of Mukti Nath Adhikari and Maina Sunwar - are likely to go unpunished.

On 16 January 2002, Mr Adhikari was teaching science at a secondary school in Lamjung district, 100km (62 miles) south-east of Kathmandu, when Maoists abducted him.

Later in the evening his body was found hanging by a tree with his hands tied behind his back, half-an-hour's walk from the school.

Maina Sunwar was arrested by a covert army team from her home near Pachhakhal in February 2005.

She was suspected of working for the Maoists and was tortured before being shot in the back in cold blood, according to a report by the army's own board of inquiry.

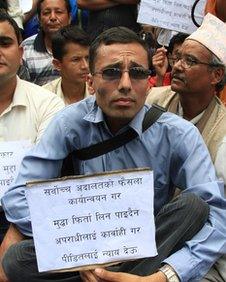

Families of war crime victims fear that atrocities will go unpunished

Despite the unrelenting media coverage these two cases have received, justice is yet to be served.

There are thousands of other cases, which are rarely reported in the media and hence almost forgotten.

"The government pays lip service and occasionally throws in some money," says Suman Adhikari, the son of Mukti Nath Adhikari.

"But the state has never been serious about finding out the truth about these war crimes."

Over the years the government has provided some cash relief to victims and their families, but survivors say that most of it has gone to those affiliated with political parties - they may not be real victims at all.

Justice has also eluded Ram Bahadur Bhandari, whose says his father was detained by security forces from Lamjung in December 2001 - never to be heard from again.

The government denies ever having arrested him and claims that he was killed in crossfire between the army and Maoists - who it blames for keeping the body.

"But the truth is there was no such crossfire in Lumjung on the day he was arrested," says Mr Bhandari.

"Dozens of people saw the security forces taking him away blindfolded."

International pressure

Frustrated with the slow legal process in Nepal, Mr Bhandari decided to take his case before the UN Human Rights Commission.

Similar cases have occasionally shone light on Nepal's perceived inability or unwillingness to deal with serious human rights violations.

Human rights activists say that it is increasingly clear that even serious offenders will go free.

"Previously politicians said that victims would have a final say on the issue of amnesty, but the language of the modified draft now says that they may [only] be consulted," says rights advocate Sapana Pradhan Malla.

Both the victims and human rights activists fear that the main parties are working to make the commission deliberately weak.

"Political parties want to give a general amnesty, but they are trying to find a backdoor to do it," says Suman Adhikari.

"I really doubt that the commission will give us justice at all."

The parties themselves originally wanted to form two separate commissions to look into past crimes: one to find out the truth about involuntary disappearances and the other to promote post-war reconciliation.

Although the two bills were pending in parliament before it was dissolved, the parties said it was their intention to form only a single commission.

But it remains unclear which issue will dominate a single commission's mandate - prosecution or amnesty?

With a budget due in mid-July and a new power-sharing agreement in the offing, many fear the issue of war crimes will be put on the back burner. The wait for justice in Nepal goes on.

- Published15 February 2012

- Published29 November 2011

- Published1 November 2011

- Published1 September 2011