A glimpse of life after Nato in Afghanistan's wild east

- Published

As the Nato summit in Chicago finalises the arrangements for handing back control of Afghanistan, the BBC's Andrew North in the east of the country examines where this leaves the people of Nangarhar and Jalalabad.

Farmer Haji Zerak greets his visitor in the usual way of Afghanistan's eastern Pashtuns.

A light touch with his right hand on the other man's left shoulder, then a warm handshake - symbolising in Islamic teaching both men's sins being washed away.

But this is not supposed to be a social call.

His visitor, the local district governor, has arrived in Achin with a posse of heavily-armed policemen and a team of labourers wielding long sticks.

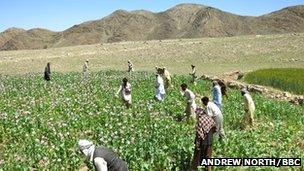

They have come to his isolated mountain hamlet in Nangarhar province to cut down Haji Zerak's fields of poppy.

The opium they produce is the source of most of Europe's heroin demand - and illegal.

But things are rarely as they seem in Afghanistan.

Deal done

For a man who says he has "no choice" but to grow poppy, Haji Zerak looks relaxed as the labourers lay into the green bulb-heads nodding in the wind.

The local authorities lack the will to eradicate all the poppy fields

It is the eradication workers who look worried.

Glancing up at the hills they urge each other to hurry.

The police have placed spotters on the ridgelines. This is Taliban country. Taxes on the drugs trade help fill their coffers.

Several eradication workers have been shot and killed in recent weeks on these slopes abutting the Pakistani border.

With a foreign television crew filming this time, their nerves are understandable.

But after a few small fields are whacked flat, they stop and leave.

A cow ambles past another terraced field of poppy below - with more beyond.

Many of the plants the workers chopped down had already flowered or been harvested. Tell-tale score-lines mark the bulb-heads, oozing dark brown opium resin.

A deal has been done.

The local authorities eradicate a few fields - but the farmer keeps most of his crop.

The Afghan authorities have neither the resources nor the will to do more - especially with such lucrative drug profits at stake.

Abandoned outposts

When I last came to these starkly beautiful hills - the "opium basket" of Nangarhar province- seven years ago, drug production was starting to fall.

Opium growing in Nangarhar is expected to rise this year

Bad weather and crop disease created better alternatives.

But this year, the UN drugs control agency predicts a rise in opium growing in Nangarhar.

We don't stay long. The hilltop lookouts radio down that local mosques are calling on villagers to look out for foreigners.

The Afghan police drive away fast in large pick-up trucks, paid for by Western taxpayers.

But although the police are up here, it is not clear that they are in charge.

We pass abandoned US outposts on the road back to nearby Jalalabad, sand spilling from ruptured blast barriers.

In the distance are the wooded peaks of the Tora Bora range, where Osama Bin Laden made his last stand against US bombers in 2001, before vanishing into neighbouring Pakistan.

There is an end-of-an-era feeling here, as the latest empire to invade these hills pulls back.

The Americans handed over security control in Nangahar to the Afghan police and army in January.

This weekend's Nato summit in Chicago is supposed to cement the handover process and work out how to pay the future bill of supporting Afghanistan.

Cricket match

Jalalabad's film-makers have received threats from the Taliban, and need heavy security in their studio

Things are better in Jalalabad, a compact city on the fertile plain of the Kabul river and famous for its fruits.

The streets are full of life.

But this is still a place on edge, not sure how much will last.

At the city's sole film studio, the Shaiq Network, better security has allowed them to make more movies.

But there is still no cinema to show them as it was closed during the civil war in the 1990s

All their films are distributed on DVD.

And they can only work behind high walls and machine-gun watchtowers.

Large cracks in their office windows tell of past Taliban bomb attacks.

When they need to cast female roles, they often have to bring actresses from Pakistan because conservative attitudes to women appearing on screen run deep.

Taliban warning letters often arrive and director Rahimullah Sapi says he's "100 per cent concerned" about the future as Nato retreats.

The Americans are still here, but cut off behind barricades of concrete and razor wire.

Their main base at the airfield - the launch pad for the operation that killed Bin Laden - was attacked again last month.

Cricket is popular in Afghanistan, and can draw many spectators

It is also now a key base for the attack drones the Americans send over Pakistan's tribal areas.

Just off the main road, a cricket match is underway - between the Nangahar Cheetahs and the Afghan Superstars.

As a bowler does his run up, a US drone flies in low over the pitch, coming in to land at the airfield up the road.

Hardly anyone in the crowd looks up.

The Americans and their allies are moving on.

And in Nangahar, people fear they are being left to bat again on their own.