Legacy of Bhopal disaster poisons Olympics

- Published

Activists say they will continue to lobby the government on boycotting the Olympics

A gentle repetitive tapping sound floats across the grass, broken by shouts of encouragement.

It is early-morning training for the Bhopal hockey squad.

The city used to be famous for the sport, and their coach, Khorshid Ali, played for India's national team in the 1980s - and was on course for Olympic selection.

But as a new Indian team prepares for the London Olympics, Mr Ali wants them to boycott the games - in protest at the event's sponsorship by Dow Chemical.

The US giant has been in the frame of campaigners ever since it bought the remnants of the Union Carbide corporation, previously the owner of the pesticide plant that leaked tonnes of lethal chemicals over Bhopal on the night of 2 December 1984.

Suffocating in his bedroom, Mr Ali remembers fleeing into the street in panic along with thousands of others.

Unsure which way to go in the darkness, many ran deeper into the toxic cloud.

Harbo Bai (left) and her husband lost their daughter in the Bhopal disaster

At least 3,000 people are thought to have died in the first 24 hours - and thousands more from the after-affects, making it the world's worst industrial disaster.

Tens of thousands of others have been left with lifelong disabilities.

For Khorshid Ali, it meant the end of his Olympic dreams.

"After that, I couldn't play good hockey," he says. "My stamina and fitness were gone."

Other Bhopal players do not agree with a boycott, and even Mr Ali admits he is reluctant to take this stand.

And there is virtually no chance of India staying away, especially with its Olympic hopefuls now doing their final training.

But it is a sign of how toxic the legacy of the Bhopal disaster remains. And that cloud has spread over to London.

Lives ruined

Nearly 30 years after the disaster, the abandoned plant still stands - with large quantities of toxic chemicals remaining in storage vessels.

Scientists and campaigners believe some of these chemicals continue to leak into the soil and ground water - causing continuing health problems.

Although about $470m (£300m) of compensation were eventually paid to victims, there is a widespread sense it was far too little.

Large sums were lost in corruption and mismanagement.

Families who lost relatives got an average of just $2,000; for injuries, the payments were around $800.

And there was no agreement on who would pay for the difficult clean-up.

Many accuse the Indian government of incompetence in the way it handled the aftermath, and of being too soft on Union Carbide for fear of scaring off other foreign investors.

Little has changed in the slums next to the plant, where thousands died when the gas cloud descended as they slept.

Harbo Bai lives in the same cramped two rooms with her husband as they did then.

They lost their daughter to the gas. It left him permanently disabled - and now he has got cancer.

Their compensation money all went on paying for medical bills - and now she cannot work because of looking after him.

"If he dies today, I can't pay for his funeral," she says.

"Look at us - even dogs and cats have a better life."

New case

Dow Chemical says it has no liability to pay more compensation or to clean up the site, as it bought the remnants of Union Carbide many years after the disaster.

It points out that India's Supreme Court approved a final settlement of claims long before, back in 1989.

However, the Indian government is now backing a new court case aimed at securing much greater compensation - provoking criticism that it does not respect its own laws.

Some suspect a certain amount of political posturing is behind calls for a boycott, with Indian officials happy to see Dow take the heat as a way of deflecting criticism of their own actions.

The positions of both India's sports ministry and its Olympic association have been noticeably vague.

Bhopal campaigners, though, insist that by buying Union Carbide, Dow is liable to pay more compensation. Activist Rachna Dhingra says they will keep up the pressure on the Indian government "to do the right thing" and boycott the games.

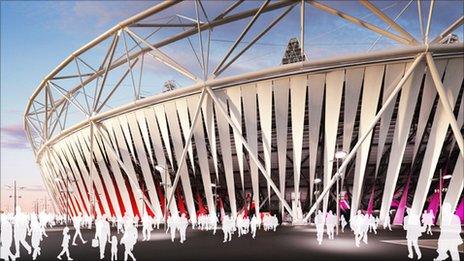

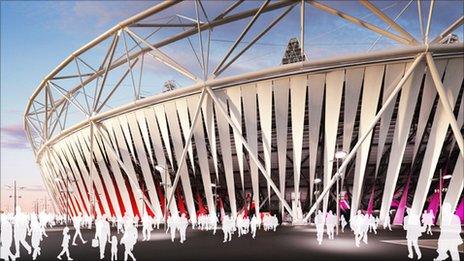

They jumped at the opportunity to publicise their cause when it emerged Dow was sponsoring the "wrap" around the main stadium.

For their part, both the London organisers and the powerful International Olympic Committee behind them have stood firmly with the company.

It has been an embarrassment for London, though, and privately some British officials wish Dow had never been taken on as a sponsor.

In Bhopal, people wish their city could be known for something other than the world's worst industrial disaster, maybe even hockey again. But first they want justice.

- Published30 May 2012

- Published12 March 2012

- Published16 February 2012

- Published26 January 2012

- Published23 January 2012

- Published20 December 2011

- Published19 December 2011