Big powers jockey in the Pacific

- Published

The US Navy is to boost its presence in the Pacific

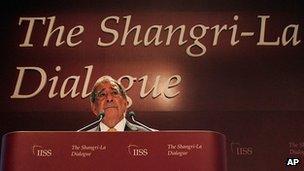

The US has been, is, and will continue to be a Pacific power. That was the fundamental message the US Defense Secretary Leon Panetta brought to this year's Asian security summit in Singapore.

Mr Panetta then headed off to Vietnam and India - two stops that highlight, in their different ways, two aspects of Washington's new security relationships in the Asia-Pacific region.

The Obama Administration having announced the so-called "pivot" back to Asia at the start of the year, it was left to Mr Panetta to fill in some of the blanks and to try to convince Washington's friends and allies that at a time of severe financial austerity the US has the means to fund its Asia-Pacific ambitions.

The rhetoric was flowing. "The US", said Mr Panetta, was "at a strategic turning point after a decade of war".

And he went on to detail some of the "re-balancing" in America's defence posture - the new term now preferred to "pivot" - that the new strategy requires.

He said that by 2020 some 60% of the US Navy would be deployed in the Pacific as opposed to about 50% today. This will include six aircraft carriers and the majority of the US Navy's cruisers, destroyers, Littoral Combat Ships and submarines.

He spoke of energising alliances and partnerships, noting the rotational deployment of US Marines and aircraft to Australia.

A host of bilateral meetings in the margins of the summit also produced results. Singapore, for example, agreed to the forward-basing of four of the US Navy's new Littoral Combat Ships - small, high-tech vessels suited to maintaining a presence in the region.

But among many participants there were still concerns about the US administration's ability to fund its resurgent Asia-Pacific ambitions. Words like agile, leaner, and so on essentially translate to fewer but more capable warships.

The US is at a 'strategic turning point', Mr Panetta said

The veteran Republican Senator John McCain, while welcoming Mr Panetta's comments, told me he was seriously worried by the spectre of draconian cuts in the US defence budget.

Ship numbers matter, he said, and the decline in the size of the US fleet, he argued, might mean that it was not able to carry out all of the missions set out by the defence secretary.

The view from Beijing

For all the talk of maritime free passage, the importance of vital sea lanes for prosperity and so on, the ghost at the feast was China.

While Mr Panetta and many other speakers stressed that the US presence and the modernisation of local defence capabilities should not be seen as directed against or intended to constrain China, it is far from clear that this is the way things are viewed in Beijing.

China was at the summit - a small clutch of uniformed officers listened intently to Mr Panetta's speech. Chinese attendance at the Shangri-La Dialogue, as the annual summit is also called, has developed to the point that last year Chinese Defence Minister Liang Guanglie represented his country.

This year, though, it was a lower-ranking officer who headed the Chinese delegation.

China-watchers here say that political uncertainties in Beijing and the ramifications of a scandal involving former top leader Bo Xilai have constrained key individuals from travelling. I understand from the conference organisers that the Chinese have assured them that next year it will be business as usual, and that no snub was intended.

China's future remains the central strategic question. Mr Panetta urged Beijing to back a rules-based system to decide competing territorial claims in the South China Sea.

But how far is Beijing prepared to go down this path, given the expansive scope of its claims and its clear determination to develop the naval muscle to back them up?

<bold>Arms race</bold> <bold>?</bold>

The Asia-Pacific region is clearly big enough for two major strategic players - the US and China. But as each appears to develop forces to counter the other, at what point does this strategic competition turn into a self-fulfilling prophecy of open competition?

Unease at China's military rise, as well as local problems like piracy and terrorism, are fuelling an arms race of sorts in the region which again, potentially could have its dangers. One of the most interesting sessions at the conference dealt with the proliferation of submarines.

An increasing number of submarines are stalking the Pacific

As Christian Le Miere of London's International Institute for Strategic Studies told me, Singapore and Malaysia have taken delivery of new submarines in recent years, and Vietnam and Indonesia have new boats on order. One senior officer said that there would be up to 170 submarines in the Pacific region by 2025.

Submarines are attractive given their stealthy characteristics, their ability to operate unseen and unsupported, at least in uncontested areas. They can be used for a variety of missions including maritime patrols, reconnaissance gathering, the landing of special forces and so on.

The spread of submarines inevitably prompts the purchase of more; another submarine is the best anti-submarine weapon. But more capable anti-submarine surface vessels and maritime patrol aircraft are also being bought.

It is perhaps too early to speak of an arms race in the region but this competitive modernisation raises some concerns.

Many conference participants called for greater transparency in the use and operation of submarines (something of a contradiction, surely, given their stealthy characteristics.) This would help to reduce the chances of submarines becoming a destabilising force.

On a visit to the main Singapore Navy command centre at Changi, I saw one small first step in this process - a multinational submarine rescue course was underway. But clearly this is an issue that will require a lot more attention in the future.

Prosperity, a rising China, the importance of trade routes and maritime tensions are all driving the process of modernisation. But improved military capabilities can be a two-edged sword, a threat as much as a defence.

This is a region where the security architecture is beginning to develop to try to meet these threats both through informal events like the Shangri-La Dialogue - one of the key drivers of multilateral defence contacts - and increasingly through more formal mechanisms like Asean Plus, that brings together the defence ministers of the Association of South East Asian Nations along with key partner countries.

- Published5 January 2012

- Published17 November 2011