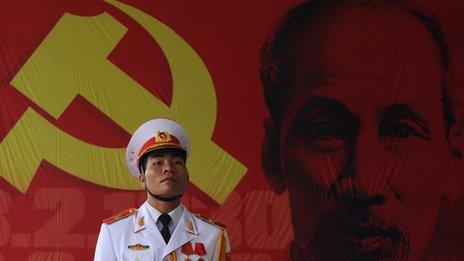

Uncle Ho's legacy lives on in Vietnam

- Published

Ho Chi Minh was the driving force behind Vietnam's struggle against French colonial rule

On an overcast morning in Hanoi, the queue stretches several hundred metres. Women dressed in traditional ao dai; schoolchildren in uniform jostling one another; grim-faced old men standing in silence; a few self-conscious Western tourists.

They are all waiting to see Vietnam's figurehead and Communist revolutionary leader, Ho Chi Minh - even though he has been dead for 43 years.

For the visitor, the enduring image of Ho Chi Minh may be the one he never wanted - the long shuffle through security checks around his mausoleum, culminating in a few seconds' hushed walk past his embalmed body. He himself wished to be cremated.

What would have been the late president's 122nd birthday this year, on 19 May, was marked by an exhibition of Ho Chi Minh documents in the province of Thai Nguyen and the launch of a translated biography, endorsed by the ruling Communist Party, entitled Ho Chi Minh - an Immortal Saint.

Women in traditional ao dai queue to enter Ho Chi Minh's mausoleum in Hanoi

The 16-chapter book chronicling the late president's life and career was written by Thai social activist Suprida Phanomjong, the son of a former Thai prime minister, who is said to have had close connections to Ho Chi Minh.

State website VietNam News said the author had been "touched to see how the Vietnamese people worshipped the president".

Public awareness

The book's Vietnamese-language launch - six years after it first appeared in Thai - was attended by a leading Vietnamese propaganda official, Nguyen An Tiem.

The state-backed Voice of Vietnam website said the publication was "expected to help raise public awareness of Ho Chi Minh Thought and his moral examples", thus contributing towards "studying and following Ho Chi Minh's Moral Example campaign".

"The fact that he lived a fairly abstemious life and that he was devoted to the cause of his country, all those things are meant to be virtues that all Communists share," says Sophie Quinn-Judge, a scholar and biographer of Ho Chi Minh.

"The problem is that it all looks a bit hypocritical and stale today because the Communist Party in the eyes of many Vietnamese doesn't stand for those things.

"Many Communists are getting rich, corruption continues to flourish: if this is the party that Ho Chi Minh represents, then people don't really want to know about it."

Every Vietnamese schoolchild is still taught about the man they call Uncle Ho - the driving force behind Vietnam's struggle against French colonial rule.

His image - ever serene and benevolent - is ubiquitous, even in the south where bitterness festers among those who lost the Vietnam war.

A large portrait hangs in the main post office in Ho Chi Minh City, the southern metropolis renamed in his honour, although in recent years the city is increasingly referred to by its old name, Saigon.

"There's no law that says you can't draw a caricature of Ho Chi Minh," says Quynh Le of the BBC Vietnamese service. "But if one appeared, it would be banned."

Ho's myth

Critics say that the lack of opposing comment on the late leader helps perpetuate the myth.

"There's a strong belief among many anti-Communist exiles and some dissidents inside Vietnam that the myth of Ho Chi Minh is linked with the legitimacy of the Communist Party," Quynh Le says.

Visitors photographing one another in front of the Ho Chi Minh mausoleum in Hanoi

"And that if the myth were removed, people would find it easier to envisage a time when the Party wasn't in power."

In the West, and among Vietnamese exiles, Ho Chi Minh is often viewed as an obdurate Stalinist as well as an anti-imperialist.

But inside Vietnam, even his detractors admit that Ho Chi Minh was less radical than other Communist leaders - and that he was seen on occasions by others in his own party as too ready to compromise.

"He wasn't all that interested in class struggle," says Ms Quinn-Judge. "At a basic level he was a believer in social justice but not in scorched-earth communism.

"Yes, he was a nationalist, but does that reflect on the rest of the Communist Party or do they have to stage some kind of apology for some of their more extreme policies that were not necessarily endorsed by Ho Chi Minh?

"The Party wants to hang onto his coat-tails for as long as possible. This is where the lack of openness and transparency gets them into trouble," she adds.

"Some liberal-minded intellectuals in the Communist Party want to portray Ho Chi Minh as a pure icon of nationalism," says the BBC's Quynh Le, "using official media to urge the party to revert to the time of his first constitution in 1946, which was more liberal.

"It's like a shorthand for saying, let's re-brand Ho Chi Minh. He's still useful for all kinds of people in Vietnam."

Take Ho Chi Minh out of Vietnam, and what is its driving force? For many Vietnamese, whatever their views of the late leader, there is no other figurehead.

- Published23 October 2024