Are there too many tourists at Angkor's temples?

- Published

Guy De Launey finds out why fears are growing about the increase in visitor numbers to Angkor Wat

The temples of Angkor have stood for as much as 1,000 years. They have survived wars both ancient and modern, as well as a period of obscurity when they were hidden by the jungle and all but forgotten.

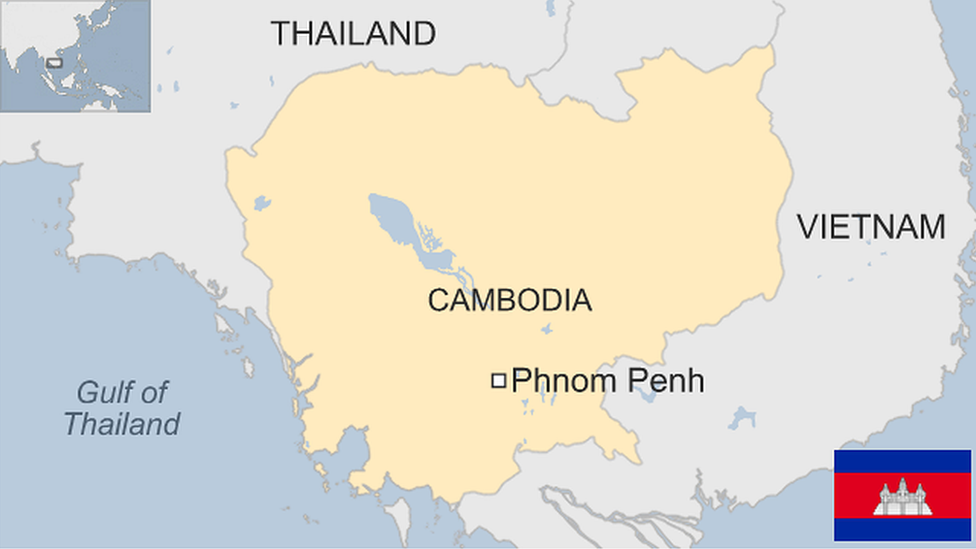

Now, as Cambodia enjoys a sustained period of peace and relative prosperity, Angkor Wat has become the symbol of the country and the pride of its people.

Its image adorns everything from the national flag to beer and cigarettes, as well as souvenir T-shirts taken home by the rapidly-increasing flow of foreign tourists.

But Angkor and its sister temples are in danger of being loved too much.

The number of tourists have risen sharply

At the start of the century, it was quite possible for an overseas visitor to spend a day at the temples without encountering another foreigner. Now, little more than a decade later, such a scenario seems like an outlandish fantasy.

The main sites buzz with tour groups from sunrise to sunset. Once, the main hazard at Ta Prohm was falling over the roots of the trees which have partially engulfed the temple.

These days a visitor is more likely to be swallowed up by the crowds striking Lara Croft poses in homage to Angelina Jolie's exploits in Tomb Raider.

Tourists press their cheeks next to the enigmatic stone faces at the Bayon and finger the bas relief carvings at Angkor Wat. But until recently, Phnom Bakheng took the unwanted prize for worst visitor behaviour.

The scene at dusk resembled nothing so much as the Cooper's Hill Cheese-Rolling, with scores of sunset-seeking visitors ignoring the safe path down from the "temple mountain" in favour of the crumbling, vertiginous steps at the front of the monument.

An ambulance was on permanent standby at the bottom.

Serious peril

Cambodia's Angkor temples are the symbol of the country and pride of its people

The climb in overall visitor numbers has been equally steep. Local officials say that 640,000 foreign tourists saw Angkor in the first three months of this year - a 45% rise compared to 12 months earlier.

Khin Po Thai has witnessed the changes. He has been working at the temples for more than a decadeas a tour guide and an employee of the conservation organisation, the World Monuments Fund.

Now, he believes the ancient temples are in serious peril.

"We have to look at the people going round, stepping on stones and carvings," he says.

"They have to respect this as a monument and a religious place. If people who continue to touch all these things then sooner or later it will be gone."

Mr Holliger says improvements need to be made to infrastructure in Siem Reap

Kin Po Thai is not alone in his assessment. A group of international experts meet the local Apsara Authority twice a year to discuss ways of preserving Angkor and their deliberations have taken on a much more urgent tone of late.

"It's a major concern. For many years Unesco has been advocating being prepared for this massive flow of tourists. And for many reasons, nobody believed in it," says Anne Lemaistre, the Unesco representative in Cambodia.

Now the experts are scrambling to find solutions - not just for the temples, but for nearby Siem Reap, which has grown from a sleepy town into the tourism hub of the country.

The transformation has come at a considerable price. Rapid development has produced results which are not always aesthetically in keeping with the beauty of Angkor. It has also contributed to clogged rivers and the removal of natural watersheds - exacerbating serious floods in recent years.

High stakes

Even the beneficiaries of the tourist influx admit there is a problem that needs to be rectified if Angkor is to continue as a big draw.

"When you arrive from the airport you don't get the best impression - it's like a hotel promenade, not very attractive," says Arthur Holliger, the General Manager of one of Siem Reap's higher-end establishments, the Hotel de la Paix.

"They need to think about the infrastructure - there are open [sewage] canals, places that smell. They need to emphasise improvements."

Projects are underway. Rivers, moats and reservoirs are being dredged so they can handle more water in the rainy season. Illegal developments which contributed to the blockage of waterways have been cleared out.

Steps are being taken to address the threats to the temple from increased tourism

At the temples, things are a little less relaxed than they used to be. There is a strict limit on the number of people allowed up Phnom Bakheng at sunset.

The upper levels of Angkor Wat are closed to tourists and wooden staircases cover up much of the soft sandstone which millions of tourist feet were eroding.

But Anne Lemaistre admits that the experts have yet to agree on a long-term solution.

"We are now building a tourist management plan. But there is still a lot of work to do. All these different measures will take one, two or three years. We need to do it in a rigorous manner; we have to make sure that everyone feels at ease - inhabitants, tourists and the authorities."

The stakes are high. Get it right, and Cambodia will have an asset which will bring in tourist dollars for generations to come.

Make the wrong choices, and temples which have lasted a millennium may be in serious trouble.

- Published6 June 2012

- Published5 March 2012

- Published3 July 2011

- Published22 August 2023