Viewpoint: Can Japan learn lessons from the Fukushima disaster?

- Published

The Fukushima disaster had its roots in Japanese culture, according to a parliamentary report

The report by the Japanese parliament into Fukushima is a refreshingly damning indictment of the relationship between the prime minister, politicians, regulators and the Tokyo Electric Power Company (Tepco).

The report outlines a string of errors and wilful negligence that left the Fukushima plant unprepared for the events of 11 March 2011, and examines "serious deficiencies" in the response to the accident.

This was a disaster "made in Japan" and the report significantly notes that "its fundamental causes are to be found in... Japanese culture: our reflexive obedience; our reluctance to question authority; our groupism; and our insularity".

Since 2006, the risk that a tsunami might knock out all power to the plant, resulting in major releases of radioactivity, was known.

The regulator, Nisa, knew that Tepco had not made preparations against such an eventuality, but did not demand action.

Indeed, there seemed to be a culture whereby the regulator would in effect ask the operator's permission before introducing any new regulations.

Nisa was created by the Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, part of whose job is to promote nuclear energy.

Tellingly, it refused to provide evidence to the parliamentary inquiry until forced by law to do so.

Deep confusion

Once power was lost on the day of the quake and tsunami, nothing could have changed the course of events, despite the heroic efforts of site staff. The foundations of the crisis had been laid in the preceding years.

As a result of this fundamental structural flaw, there was deep confusion and conflict over the roles of the various agencies once the crisis began.

Particularly unhelpful was the action of the office of Prime Minister Naoto Kan, which failed to declare an immediate state of emergency.

Mr Kan himself visited the site and issued operational instructions on 15 March, something that seriously muddied lines of responsibility.

Perhaps most strangely, it seems that far from the prime minister being key in dissuading the plant personnel from withdrawing from the site, as he has claimed, this had never been considered by Tepco or anyone else.

There are striking observations to be made.

The risk of a tsunami knocking out all power to Fukushima had been known since 2006.

The first is how many lessons of the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl accidents seem not to have been applied in Japan.

At Fukushima, like at Three Mile Island, information about certain safety dangers which had been recognised before the accident did not reach the site operators.

Like at Chernobyl, psychological illness will hugely outweigh that associated with radiation, yet there has been little attention given to minimising such damage by providing honest and reliable advice and information.

The Chernobyl instruction manuals, like Fukushima's, also had large sections missing.

History of shame

More tragic in a way, however, is that this parliamentary report could equally well have been written in 1999, 2003 or 2006.

In 1999 nuclear fission processes started up in a bucket in a fuel processing plant at Tokai village (which was not Tepco's responsibility), killing two workers.

In 2003 Tepco had to close 17 of its nuclear plants after a scandal about falsified safety records; in 2006 it reported it had falsified temperature records at Fukushima in 1985 and 1988.

Yet despite this history of shame, no effective action was taken by regulators or the government to pull the company into line.

Widespread public protests against Tepco and nuclear power suggest that at last the Japanese people might be starting to give the regulators and industry the robust challenge that nuclear companies have both suffered from and benefited from in the West.

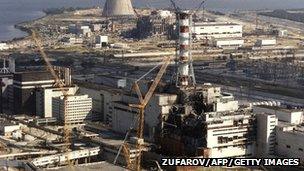

The Chernobyl disaster in 1986 saw similar failings to those seen at Fukushima

Whether a safe and trusted nuclear industry emerges, or whether the political obstacles are now too high, only time will tell.

On 4 July Japan restarted the Ohi Unit 3 reactor, the first to be restarted since the accident some 16 months beforehand.

Others will doubtless follow - but, even so, Japan is many miles away from where it was just two years ago, planning to expand nuclear power to 50% of its electricity production by 2030.

Yet the challenge Japan has always faced in energy has not changed because of Fukushima.

It is already one of the most energy efficient economies in the world, but it depends on imports of oil, gas and coal for 84% of its energy needs.

Unlike Germany, which is phasing out nuclear power against a background of owning huge reserves of coal and enjoying easy access to imports of electricity and gas from neighbouring countries, Japan is largely isolated from direct connections to the mainland.

The world's third largest economy has huge energy needs, even leaving aside its commitments to reducing greenhouse gas emissions under the Kyoto protocol (a matter of obvious national pride).

The nuclear debate in Japan may not be over, but if nuclear power is ever to prosper there again, Japanese people will have to abandon their "reflexive obedience" and their "reluctance to question authority" and subject the government, regulators and industry alike to sustained and robust examination.