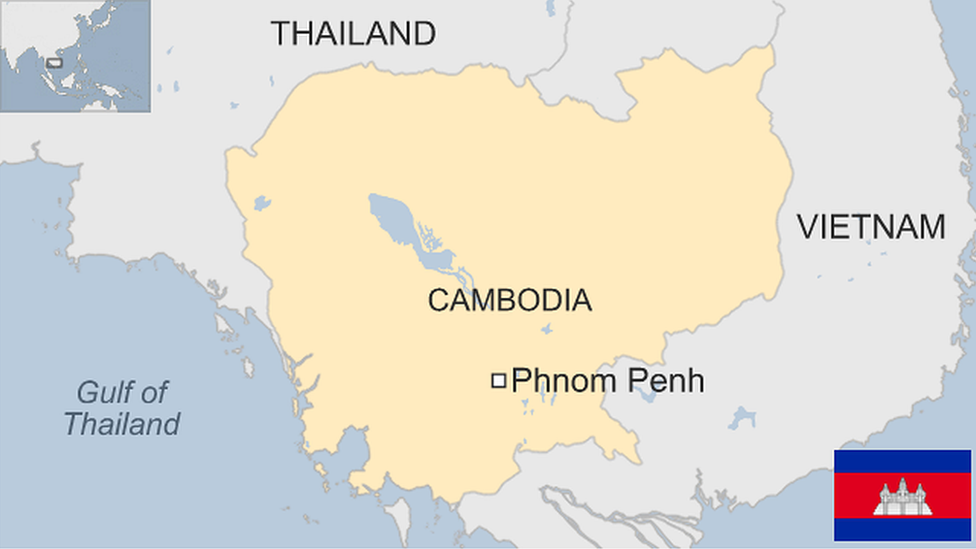

Explaining Cambodia's 'mystery illness'

- Published

Villagers lined up for medical checks outside the Kuntha Bopha children's hospital in Phnom Penh

It must be every parent's nightmare - reports of a mystery disease killing dozens of children.

Sixty undiagnosed deaths over a period of three months triggered a report from the Cambodian authorities to the World Health Organisation (WHO). In such cases, there is usually an internal investigation to discover the facts before anything is made public.

This time, however, the report was leaked to a news agency in the Philippines. It soon made international headlines, perhaps understandably, bearing in mind that diseases like SARS and bird flu had first been identified in this region.

But it turned out that the unidentified illness was nothing remotely so serious.

'Needless panic'

Working together with Cambodia's Ministry of Health, the WHO found a virus known as EV71. It was the first time it had been positively identified in Cambodia, but it is common in nearby countries, including Vietnam and China.

It is one of the triggers for hand, foot and mouth disease - a childhood illness that is well-known around the world.

For most children, it causes nothing more than a few days' discomfort. But for those already weakened by malnutrition or diarrhoea, it can become more serious if not properly diagnosed and treated.

.jpg)

Dr Pochenda Chhorn cites low hygiene as a major reason for disease

Most health experts in Cambodia were bemused by all the fuss. One told the BBC that treating the illness as a news story would be "like covering an outbreak of chickenpox".

Dr Beat Richner, the Swiss national director of Phnom Penh's Kantha Bopha Children's Hospital, berated the WHO for causing "needless panic" in its handling of the affair.

But officials at the WHO are themselves privately seething that what should have been an internal report ended up going viral, spreading alarm before all the facts were known.

The fuss over the affair will probably die down soon. But some health workers hope that it will at least illuminate the challenges facing Cambodia, especially its young children.

Toilet access

Sixty deaths over three months may seem a lot, until one realises that 50 children under the age of five die in Cambodia every day.

Over a year, that comes to almost 20,000. In all, one in 20 Cambodian children will not live to see their fifth birthdays.

The reasons are tragically simple. Dr Pochenda Chhorn sees them every day at the Cambodian Children's Fund Clinic on the outskirts of Phnom Penh.

"They live in very poor conditions. They have low hygiene - this is the biggest cause of disease for them," she said.

It is a staggering statistic, but true nonetheless: Cambodians are more likely to own a mobile phone than have access to a toilet. In rural parts of the country, the vast majority lack sanitation and the consequences are predictable.

Children in Cambodia are vulnerable to infections because of poor hygiene

Diarrhoea is one of the main causes of death for the under-fives. Even when it does not kill, it leaves children vulnerable to other infections, including hand, foot and mouth disease.

Simple advice

The WHO's advice for reducing the spread of EV71 and HFMD is simple: wash hands and practise good hygiene. If children develop a fever, treat them with paracetamol.

Despite the recent scare, and the high under-five mortality rate, the WHO is keen to emphasise the progress Cambodia has made. As recently as a decade ago, one in eight children died before they reached five.

Dr Howard Sobel, the WHO Maternal and Child Health Team Leader in Cambodia, says that credit should be given to the government's promotion of breast-feeding.

"These days, three out of four mothers practise exclusive breastfeeding. It used to be one in 10," he says.

Mr Sobel also praises the government's efforts to restrict the advertising of infant formula milk and says the campaign and its results have been remarkable for such a small, developing country.

If that level of commitment could be applied to sanitation and child nutrition, then further success may come. Cambodia's children would then be much less vulnerable to the likes of EV71 and hand, foot and mouth disease.

- Published22 August 2023