Has Chinese power driven Asean nations apart?

- Published

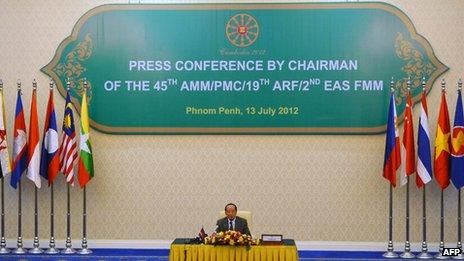

South China Sea tensions left host Cambodia with no joint statement to read

"Welcome to the Kingdom of Wonder," say the signs at Phnom Penh airport.

High-level delegates from the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean) were certainly left scratching their heads as they departed after a week of meetings which ended in embarrassing disarray.

Other banners prepared by the host country featured the official slogan of Cambodia's year in the chair of Asean: "One Community, One Destiny". That has an awfully hollow ring to it now.

For the first time in the association's 45-year history, the foreign ministers from the 10 member countries were unable to agree on a closing statement.

For all the high-profile security, pomp and ceremony, it was as if the bewilderingly-titled events (the "45th AMM/ PMC/ 19th ARF/ 2nd EAS FMM") had never happened officially.

The reason: China.

Four Asean members are in dispute with Beijing over the sovereignty of the South China Sea - with the Philippines and Vietnam involved in particularly tense arguments.

But the poorest of the association's members have received billions of dollars in aid and investment from China in recent years.

And - fairly or not - during Cambodia's time in the Asean chair, it has faced accusations of doing Beijing's bidding rather than supporting its colleagues.

Cambodia has tried - as far as possible - to keep the South China Sea issue off the agenda of Asean meetings.

Its refusal to allow a reference to the Philippines' dispute with China stymied attempts to issue a closing statement following last week's meetings.

It seemed to confirm the worst fears of diplomats about Asean's vulnerability to conflicts of interest caused by China's influence in the region.

With the United States also attempting to increase its engagement, Asean risks being caught in the middle.

"A great game is being played in this part of the world," said Japan's ambassador to Asean, Kimihiro Ishikane.

"For Asean to play an important role, it must keep its centrality - its mind-set of independence."

'Balancing act'

That is easier said than done. Comparisons are sometimes made between Asean and the European Union - especially as the former moves towards greater economic integration.

But the differences between, say, Greece and Germany are nothing compared to the yawning chasm between Laos - one of the poorest countries in the world - and Singapore, which is one of the wealthiest.

Finding common ground is sometimes a challenge - and countries like Cambodia may feel that China can offer them more assistance in development than their neighbours.

Marty Natalegawa says Asean nations need to rebuild unity and get back on track

So Asean is in a tricky position. Its rising economic clout has led to increasing interest from the rest of the world. And since the adoption of a charter four years ago - which makes its decisions binding - it has been taken more seriously as an international player.

But this is attracting attention which has the potential to split its membership. The association's secretary general, Surin Pitsuwan, told the BBC that Asean was now strong enough to deal with it.

"This region has become more important to the world - they don't want it to be derailed, they don't want any conflict to affect the growth trajectory of this region. We are more important to the world than five years ago," said Dr Surin.

"We knew the game all along - we need to play this balancing act. We need to serve as a fulcrum of all sorts of power plays in the region. We can't keep anybody out - because everybody has legitimate interests in the stability and security of this region."

But if it is indeed a balancing act, then last week Asean took a tumble - raising serious questions about its future.

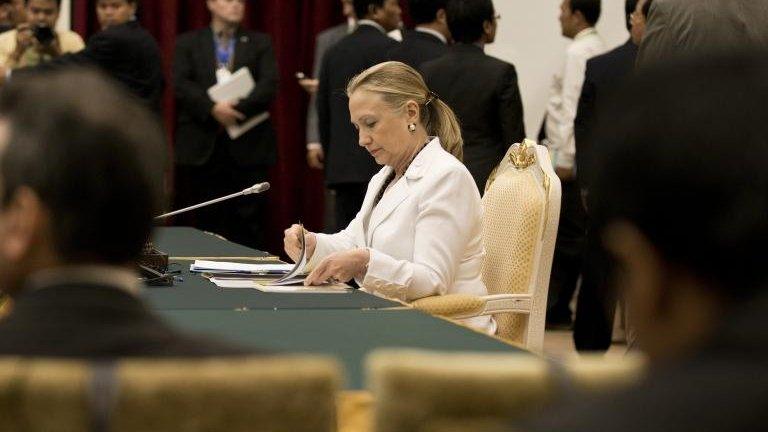

As the largest member, Indonesia was quick to move to heal the wounds.

Its foreign minister, Marty Natalegawa, has embarked on a round of what he calls "shuttle diplomacy" - an effort to patch things up among the quarrelling members.

Following visits to Manila and Hanoi, Mr Natalegawa arrived in Phnom Penh to try to agree a common stance on the South China Sea issue.

"Last week wasn't a pleasant experience - it was very un-Asean, the lack of consensus," he told the BBC.

"But Indonesia believes we can have more influence if we are united. We need to quickly get ourselves back on track."

Mr Natalegawa said he was confident the members would reaffirm their unity. The problem, he said, had been with details of specific incidents being included in a statement - rather than a deeper philosophical split.

"Let's not labour on the specific incidents - but build the capacity of Asean to deal with these incidents."

Above all, Mr Natalegawa hopes that last week's events in Phnom Penh will prove to be an "aberration" rather than a new norm for the association.

He points to Asean's role in cooling the tensions at the Thai-Cambodia border as evidence of how successful it can be in forging consensus.

But now there can be no doubt about the main challenges to Asean's chances of becoming a serious geo-political player.

As the "great game" warms up, its community will be tested - and its destiny remains in the balance.

- Published13 July 2012

- Published12 July 2012

- Published7 July 2023

- Published10 July 2012

- Published25 May 2012