Kazakh US exhibition banishes country's Borat image

- Published

The exhibition shows that Kazakh culture stretches back thousands of years

In the 2006 spoof documentary Borat, the eponymous hero travels from Kazakhstan to the US to learn about the American way of life.

Given the subtitle Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, the film is a sometimes funny and often discomforting send-up of American social values.

But many audiences remember more vividly its portrayal of Kazakhstan as a backward nation populated by peasants with little in the way of culture.

So indelible is that image that at a sporting event in Kuwait earlier this year, the film's theme music was accidentally played during the award ceremony instead of the real national anthem of Kazakhstan.

But now that stereotype is being blown apart by an exhibition in Washington DC of ancient treasures that reveal the true "glorious nation of Kazakhstan".

Myths dispelled

Many of the artefacts comprising Nomads and Networks, on show at the Smithsonian's Freer and Sackler Asian Art galleries, have only recently been discovered and have never before been displayed outside the country.

Many of the items on display are exquisitely made

"Such exhibitions are very important in terms of establishing a national identity and to show Kazakhstan to other people," says Dr Bauyrzhan Baitanayev, Director of the Margulan Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences in Kazakhstan.

"It's very clear to me that not a lot of people know what Kazakhstan is. In New York, people kept asking me about Pakistan and I had to explain, no, it's another country."

The exhibition aims to dispel the myth that the nomadic horsemen who traversed the Eurasian steppes during the era of the Persian Empire were culturally inferior to other communities that had settled.

The Persians called the nomads Saka and regarded them as fearless warriors. One of the earliest written references comes from the Greek historian Herodotus.

Intricately carved stone rock engravings reveal a communications system that helped the Saka navigate the landscape while ancient burial mounds known as kurgans have yielded exquisite horse decorations in bronze, gold and horn that show a high calibre of craftsmanship.

"We have a popular image of nomads that is no longer accurate," says exhibition curator Alex Nagel. "New research has made clear that nomadic culture was much more complex."

Protected by permafrost

The ability to trace a unique cultural heritage dating to the first millennium BC is important for the fledgling Kazakh nation. Having gained independence from Soviet Russia in 1991, the government is using the nation's treasures to help establish a modern identity.

Ancient burial mounds have been discovered in parts of Kazakhstan

"And they have the money to do it because of the country's mineral wealth," says Simon Williams, the director of the British Council in Kazakhstan which is close to completing a joint programme to translate museum information into English.

According to the country's Ministry of Culture, there are 136 museums already in Kazakhstan and ambitious plans are under way to build a National Museum in the new capital Astana. The ministry says it will be 85,000 sq m (915,000 sq ft) and the biggest museum in Central Asia.

"The first years following independence were quite rough. People were not getting paid salaries and no attention was paid to research," says Dr Roza Bektureyeva, Director of Kazakhstan's Museum of Archaeology.

"But in the last few years the state has paid a great deal of attention to the development and funding of science."

That has enabled much of the recent excavation work to be carried out by graduates from universities in Kazakhstan - work that was once done by Russian archaeologists.

The items on display are beautifully and intricately made

And there is a lot more to discover. Much of the country's antiquity has been protected by permafrost which scientists exploit to preserve the treasures they find. Frozen blocks of earth are taken to refrigerated laboratories for further examination.

In this way, fragile materials, such as an embroidered saddle cloth remain in excellent condition with the red pigments used in the vegetable dyes still plainly visible.

Silent communion

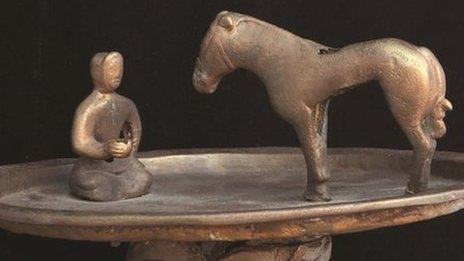

The relationship between man and horse is a central theme of the exhibition that often raises more questions than it answers.

For instance, mystery surrounds a series of raised bronze trays studded with miniature animals. One in particular features a human figure kneeling in front of a horse that in turn bows its head. The two appear to be in silent communion, connected by a spiritual bond.

"We're still trying to figure its original function - maybe an incense burner," speculates Mr Nagel. "But nobody really knows."

The ancient Kazakhs were heavily dependent on their horses, using horse bones to construct houses and drinking mares' milk to survive. And horses are still important today.

"Many of these objects remain the symbols of independent Kazakhstan and this research has really helped us form our modern identity," says Dr Bektureyeva.

"There was a theory that the Saka, the ancient warriors, were barbarians - but they had a great culture and it's important to present that," says Dr Baitanayev.

"We can judge whether or not they were barbarians by looking at this wonderful and unique collection. American visitors will be able to draw their own conclusions about the history and culture of Kazakhstan."

But will it be enough to banish the legacy of Borat?

"There is no comparison," says Dr Baitanayev angrily. "It's not even a subject for conversation."

- Published24 March 2023