Viewpoint: Consequences of pandering to Pakistan extremists

- Published

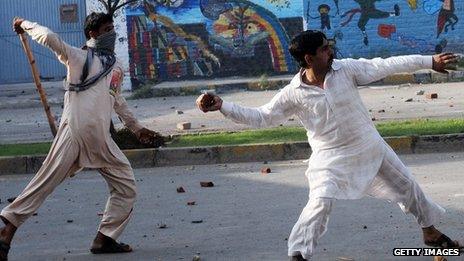

Religious and extremist groups played a significant role in leading protests on the streets of Pakistan

Pakistan is paying a devastating price for pandering to extremists and allowing them to dictate the political agenda, argues writer Ahmed Rashid.

In Pakistan, as elsewhere across the Muslim world, there is a sense of powerlessness against Western governments and media companies who want to uphold the right of free speech but publish explosive material that enrages Muslims.

A growing sense of economic and political powerlessness is leading to support for extremist views.

And the refusal of the West to meet half-way on containing hate material is being further fuelled by extremists who find it convenient to stake their claim in such troubled moments. This is particularly true in Pakistan, which has been pandering to extremists for three decades even as the state appears to be losing control of the streets.

On Friday 21 September, some 21 people were killed, including three policemen, and more than 200 injured as mobs protesting against a US-made film mocking the Prophet Muhammad went on rampages against private property and fought running battles with the police.

Islamabad's diplomatic quarter was under siege as police fired live ammunition.

The Pakistan Peoples Party government appeared to abdicate all responsibility for maintaining law and order with its questionable decision to order a holiday on Friday and yet give no political direction - a move which allowed mobs to take control of the streets.

Three 'watersheds'

The riots represented the third watershed moment for Pakistan where the state has repeatedly yielded, for a time, to the demands of a handful of extremists, thereby not just weakening the state but strengthening those extremists who want to overthrow the system.

In January 2007 then military ruler President Pervez Musharraf and his pliant Prime Minister Shaukat Aziz allowed the Red Mosque in Islamabad to be taken over by extremists in a cynical effort to try to influence US fears about a fundamentalist takeover and so relax US pressure on the army to end safe havens for the Afghan Taliban.

It took seven months of deliberate procrastination before Gen Musharraf decided to send in the army and oust the thousands of militants in a pitched battle that left 102 people dead, whereas in January a handful of police could have achieved the task.

It was a watershed event because thousands of militants escaped into the hills leading to a rapid expansion and strengthening of the anti-state Pakistani Taliban.

After extremists murdered two prominent politicians in 2011, including Salman Taseer, the governor of Punjab province and later a Christian federal minister, no politician or journalist has since dared oppose the law or demand changes to it or discuss the issue of changes to the blasphemy laws.

Pakistan's blasphemy laws invariably persecute those belonging to other religions and Muslim minority sects on the flimsiest of evidence or none at all.

After the two officials were killed, the government withdrew amendments to the blasphemy law it had sponsored in parliament, capitulating to the fundamentalist viewpoint. This too was a kind of watershed because, since then, genuine debate has been silenced out of fear.

Last week's riots in response to the film were not just spontaneous events around the country. Leading the riots were the religious parties that accept the parliamentary form of government, but also extremist and terrorist groups banned by the government and the United Nations.

There was genuine anger felt by Muslims everywhere regarding the desecration of the Prophet

Riots in Lahore and many parts of Punjab were led by the banned Lashkar-e-Taiba whose militants are presently fighting in Afghanistan, Indian-administered Kashmir and Central Asia.

Sipah-e-Sahaba, a militant Sunni group that wants to "cleanse" Pakistan of all Shia Muslims and has claimed responsibility for the murder of more than 300 Hazara Shias in Quetta alone this year, openly led the demonstrators in other parts of Punjab (nobody has been caught for the murder of so many Shias).

The Pakistani Taliban and their supporters were in the forefront in Karachi and Peshawar where they have considerable assets.

But vast areas such as rural Sindh, Balochistan and even parts of the north-west saw no riots or demonstrations because the militants' network of mosques and madrassas were weak or non-existent.

Nowhere did the government even bother to organise a peaceful demonstration of its own supporters to express outrage but at the same time maintain the dignity of the government.

Cutting a deal?

At other times the government and the military have deliberately fuelled the appearance of extremism in order to pressure, influence or blackmail US or Nato decision-making for Pakistan and Afghanistan.

According to religious figures, in January 2012 the military and intelligence services mobilised dozens of Islamic parties, militant groups and retired generals to form a platform called the Defence of Pakistan Council. They held nationwide street protests against the Americans and Nato after the government had closed the Nato supply road to the Afghan border, after 24 Pakistani soldiers were killed by US forces.

The road that provides Nato forces with goods from the port city of Karachi stayed closed for seven months, creating widespread mistrust of Pakistan among its allies and enormous economic hardship.

Yet, mysteriously, when the military decided to cut a deal with the US and reopen the road, the Council just as suddenly disbanded and disappeared from the streets. The establishment had demonstrated to the Americans its obvious influence over extremist groups.

Likewise Pakistan gives shelter to the Afghan Taliban leadership even as the state battles other groups of the Pakistani Taliban. The question is then obvious - why can't the state deal with the threats such extremists now pose?

Pandering to the extremists or using them as a foreign policy tool in the long-running war of wills between Pakistan and the West has only strengthened extremism in civil society, the army, the bureaucracy and the police.

The state machinery itself is penetrated and undermined, with not a single politician or general urging change. Pakistan is on the cusp of a nightmarish scenario where extremists call the political shots and the government obeys.

There was rightfully genuine anger felt by Muslims everywhere regarding the desecration of the Prophet, but the cost Pakistan is paying for its leaders deliberately allowing extremists to take control of the streets and cities is devastating for the majority of Pakistanis.

Ahmed Rashid's latest book Pakistan on the Brink, the future of Pakistan, Afghanistan and the West was published this year.

- Published21 February 2012

- Published21 September 2012

- Published3 July 2012

- Published6 January 2011