Successes and challenges in Afghan girls' education

- Published

One girls' school in Kabul has a cricket team - unthinkable during Taliban rule

The fields of Bamyan province are dotted with people at this time of year, heads down digging in the earth.

It's potato harvest time and children are helping too - as they have done for centuries.

But one thing has changed: many of the young girls working with their families are also going to school for the first time.

In between dropping fist-sized potatoes into a bucket, 10-year-old Hamida says that, until last year, "I'd never been to school."

She is one of 3.2 million girls now getting an education in Afghanistan, according to Unicef.

It's a dramatic rise from 2001 when the US-led invasion brought to an end the Taliban ban on girls going to school.

The female literacy rate has tripled - but at around 13%, it is still one of the world's lowest, a sign of how far Afghan girls and women have fallen behind in the past three decades of conflict.

Conservative attitudes

Even before the Taliban took power, women's rights were squeezed.

And although Afghanistan's new constitution says men and women "have equal rights and duties before the law" in practice women remain a distant second to men in this patriarchal society.

Child marriages remain common, and stories of abuse keep coming to light.

One of the worst cases involved Gulnaz, who was raped by her cousin's husband then charged with adultery after she became pregnant.

She gave birth to her daughter while in jail before an international outcry led to President Hamid Karzai granting her a pardon last year.

He has come under fire himself from women's groups for not taking a stronger stand. They have accused him of keeping his wife in the palace and out of the media's reach - because of fears he will be criticized by conservative religious leaders.

Yet the changes for girls are clear on a visit to the Suriya school in Kabul.

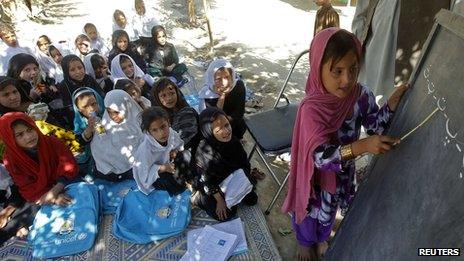

The female literacy rate has tripled but is still one of the world's lowest

Many of the girls here were born around the time American bombs were falling on Afghanistan in 2001, so they have no memory of the tough years before.

In the yard outside, the girls' cricket team is practising under the tutelage of a male coach - unimaginable under the Taliban - who only allowed women to venture out with a close male relative.

A UK charity, Afghan Connection, has been helping, providing equipment donated by British schools.

London's Marylebone Cricket Club is also giving support.

Inconsistency

Safe within the walls of their school, they are like children anywhere, curious about their visitors and keen to talk about themselves.

There is anxiety about what will happen when US troops leave the country

"I want to be a journalist too," says one 12-year-old, when they find out who these visitors are.

But outside Kabul and other big cities the changes are more patchy.

Most Afghans still live in rural areas, where poverty, conflict and conservative attitudes are more likely to keep girls and women at home.

Of the 4.2 million Afghan children not getting any education, Unicef estimates 60% are girls - and most live in rural districts and the southern and eastern provinces where Nato-Taliban clashes have been most fierce.

These are also the heartlands of the Pashtuns, the ethnic group from which the Taliban emerged and who have always had the most conservative views of a woman's role.

More schools are being built outside Afghan cities - but far less in this conflict belt. Even then, the Taliban have forced many to close again.

It's dangerous trying to be a teacher in southern Afghanistan.

US withdrawal

There's some anxiety too over whether the momentum of change for Afghan girls will last once the Americans pull out in 2014.

Afghanistan's Education Minister Farooq Wardak - a possible future presidential candidate - insists it will.

At an opening ceremony for a new school in much safer Bamyan, he says only when women feel they are "the owner of this nation... can we make Afghanistan".

Afghan Connection has funded the construction of more than 30 schools and is encouraging the focus on rural areas.

Director Dr Sarah Fayne says the key is winning acceptance, "making sure schools are close to where people live, so girls don't have to walk far and that they have female teachers".

But she's convinced the changes of the past decade are now permanent.

"I can't believe people who have let their kids go to school will allow that to be taken away."

Back in her Bamyan village, Hamida still has a lot of work to do in the family home, helping look after her younger siblings as well as in the fields.

But six days a week now, she makes the 2km walk uphill to her local school perched on a mountainside.

"There was no school in my time," says her mother - only 30 years old.

"My daughter wants to be a doctor. May God help us, so her dreams come true."

- Published10 October 2012

- Published4 July 2012

- Published18 August 2012