China new leaders: challenges ahead

- Published

China's ruling Communist Party has unveiled a new set of leaders.

Economic reforms have transformed China into the world's second-largest economy. But its 1.3 billion population and continental size mean the problems these new leaders face are still daunting.

These are the issues set to be top of their agenda.

Change the model

China's economic success has lifted 500 million people out of poverty. Yet the economic model that worked so well during the early years of China's development now needs to change.

Chinese and Western analysts say the economy must be rebalanced to give more weight to consumers instead of investment, much of which is government-led and wasteful.

State-owned companies which dominate many sectors need to be opened up to competition.

And, instead of championing these state-owned giants, the government must give more support instead to small and medium-sized companies, because these are likely to be the providers of future growth and jobs.

China's government agrees with these goals, at least in its official pronouncements. The problem is it has done little to address them.

Supporters say it was sidetracked by the global financial crisis, which prompted a huge stimulus package rather than structural reforms.

Critics argue China's one-party state is too compromised by vested interest groups, political concerns and corruption to introduce the needed changes.

They point to the state-owned sector, which produces only half of China's GDP but gets the benefit of more than 70% of its bank lending, at artificially low interest rates.

Huo Deming, an economist at Peking University, says it is "unthinkable" for the state-owned sector to be forced to retreat.

"The state-owned enterprises will expand again, China's political leaders want them to compete with the US and other countries, so further strengthening them is a must," he says.

Inequality

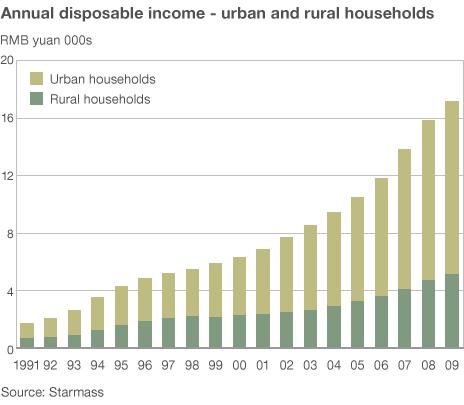

Everyone is much better off than when China began its economic reforms in 1978.

But incomes in the cities have risen far faster than in rural areas, while rich coastal provinces have powered ahead of the poor interior. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences says the gap between urban and rural incomes has jumped 68% since 1985, creating one of the widest wealth gaps in Asia.

The government is worried the gap could spark social unrest. It points to poverty eradication programmes in poor provinces like Sichuan and its abolition of a centuries-old agricultural tax as proof of its commitment.

It has also vastly expanded healthcare insurance, increasing the number of people covered ten-fold to 830 million, and education.

Yet critics say much more needs to be done, and point out that China spends only about 6% of GDP on social welfare, about half the level of countries at a similar level of development.

Part of the problem is China's governance system. Social spending is largely the responsibility of local governments, which say they do not have enough money, however much Beijing hectors them.

Environment

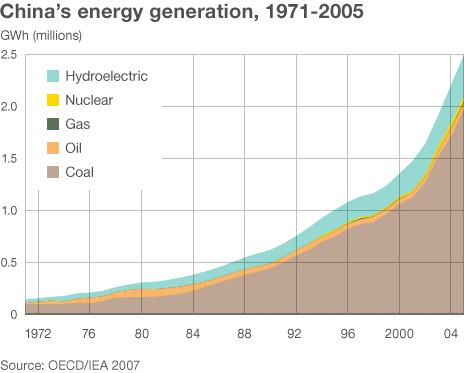

China's explosive growth has created some of the world's most complex environmental challenges.

It is now the world's biggest emitter of greenhouse gases, yet will continue to rely on coal as its main energy source for the foreseeable future.

New wealth has seen the number of cars on the roads quadruple since 2003. Yet China is already home to 20 of the world's 30 most polluted cities.

The central government well understands the problems. It points to success stories like the restoration of the Loess plateau in the country's north-west, and the fact that wind turbine capacity has doubled every year since 2005.

It has also put in place the legal and regulatory framework for tackling environmental problems, though implemention - especially at the local level - remains patchy.

And, alongside the task of cleaning up a "high growth, high pollution" past, China still faces basic development challenges.

"They've made huge gains, but there are still 480 million people without access to sanitation, and nearly 120 million without access to water supplies," says Joanna Masic of the Asian Development Bank.

Rising expectations

As Chinese people have become richer and better educated, their expectations have drastically changed.

They no longer just expect the next generation of leaders to run an economy that creates jobs and wealth, they want better services and greater freedoms too.

More than 6 million people graduate from Chinese universities every year, a six-fold increase since 1998. More than 500 million people use the internet, especially a micro-blogging site called Sina Weibo. Smart phones are helping drive social activism and, sometimes, environmental protests.

There is conflicting evidence as to whether people are happier, as well as richer.

Analysis by Richard Easterlin, of the University of Southern California, suggests China's wealthiest third were more satisfied with their lives in 2007 than in 1990, but the rest of the country was not.

Part of the reason may be aspirational. People know their lives have improved, but think other people are doing even better.

Demographics

China's fertility rate is one of the lowest in the world, in part because of the one-child policy. This restricts urban couples to having only one child, unless both partners are themselves only children.

As a result, China has fewer and fewer young people to pay for the pensions and healthcare of more and more elderly.

The working-age population is set to start shrinking from 2015, adding to pressure on wages. China will also soon have more senior citizens than the EU.

The one-child policy has also created anomalies. Some parents who want boys abort fetuses which ultrasound scans show to be female. China now has about 120 male births for every 100 female births, and there are estimates that by 2020, 24 million single men will be left without potential partners.

Academics and government think tanks have called for the policy to be scrapped, which would be popular with young Chinese and could help restore China's fertility rate.

But no senior leader has publicly backed any changes, which some officials appear to worry could lead to a population explosion.