Displaced and divided in Burma's Rakhine

- Published

The BBC's Jonathan Head says the violence in Rakhine state casts an ''ugly shadow'' over Burma's democratic journey

In recent months, communal violence in Burma's Rakhine state has left about 140 people dead and forced more than 100,000 from their homes. With Buddhist and Muslim communities effectively segregated, divisions seem deeper than ever, the BBC's Jonathan Head reports from Rakhine.

A British colonial official returning to Sittwe, or Aykab as it was known in the days of empire, would surely recognise most of it. Cycle rickshaws still dominate the dusty streets; the decaying buildings seem from another era, well before the prosperity of the Asian century.

Aside from a prominent golden stupa, a rooftop view of the town shows only rusting iron roofs amid a sea of coconut palms, and the shimmering waterways behind that carve up the coastline in this part of Burma, near the Bangladesh border.

Rakhine is the second poorest state in Burma, already one of the least-developed countries in the world. Poverty, neglect and repression have played a big role in fuelling the communal violence, as have bitter historical memories, and the fears felt in rival communities of what might be lost or gained in Burma's new and uncertain political environment.

The UN and other international agencies are already supplying emergency assistance to many of the 110,000 people who have been displaced by two bouts of brutal clashes between Muslims and Buddhists. But there is still dire need.

I spent a day in the village of Thechaung, a few kilometres outside Sittwe. This is a Rohingya Muslim neighbourhood, one of the few left untouched by attacks from Buddhist mobs. This was already a very poor community; the only substantial building is the wooden madrasa [religious school], under which dozens of displaced families are now camping.

Thechaung is hosting around 2,500 Muslims from elsewhere, mostly from Nazih, an areas of Sittwe destroyed in the June violence, and from Kyaukpyu, which was razed to the ground in sustained attacks on 23 and 24 October.

As it is not an official camp, Thechaung is getting no assistance from the government or international agencies. Charity donations of food, mostly from Rohingyas living elsewhere or overseas, are keeping the swollen population alive. I watched a cauldron of beef curry, made from a donated cow, being served out, two lumps at a time, to each family.

Under the madrasa, the family of 45 year-old Sura Katu grieved loudly over her emaciated-looking body. She fled from Nazih in June and died, they told me, of a fever that morning.

Sura Katu was one of many forced to flee by the violence

Muslims are now confined to these shrunken zones of safety, barred from going to town for work, shops or hospitals by their well-justified fear of attack. Buddhist monks have demanded a boycott by Sittwe's traders of any Muslims who might dare to try shopping there. No-one breaks it. The two sides are now completely segregated.

There are displaced Rakhine Buddhists too, also in real need of help. Some have been sheltering in temples, others in camps the government has set up. But their numbers are far smaller than the Muslims - less than 10% of those displaced, according to aid workers - and they can move around more freely.

'Chronic neglect'

Testimony from the displaced Muslims paints a picture of planned, organised attacks in October in a number of places at once. The destruction of the Muslim neighbourhood in Kyaukpyu is especially revealing.

The inhabitants there are mainly Kaman Muslims, relatively prosperous traders and boat-owners who, unlike the widely-despised Rohingyas, are recognised as citizens by the government. They never expected to be a target.

But they described armed Buddhist mobs attacking from all sides, systematically burning every building, and, they said, being supported by the police and army. Some showed me bullet wounds sustained during the clashes, from guns fired into the neighbourhood from outside. Repeatedly I was told that pleas for protection from the security forces went unanswered.

A mosque in Pauktaw village was one of many buildings razed to the ground

Rakhine Buddhists have a different story to tell. They repeat the accounts spread by word of mouth or through internet sites of gruesome Muslim atrocities, and occasionally bring out blurry photographs of mutilated corpses.

But theirs is a much longer story, of chronic neglect by the central government, and of what they believe is uncontrolled Muslim population growth, which threatens to swamp them. They are frightened of the spread of extremist Islamic ideas, especially among young Rohingya men who have lived in Saudi Arabia.

Ashin Ariya Vunsa, abbott of the old Shwe Zedi monastery in Sittwe explained why, in his view, the communities could no longer live together. The Muslims take too many wives and have too many children, he said - and they abuse Buddhist women too. They don't allow women to be educated.

Those who are legal citizens, who have citizenship cards, can stay, he said - but they must become more like us, learn from our culture. As for those who are illegal - they should be confined to camps, he said.

That is in effect what has happened to tens of thousands of Muslims. The term "Rohingya" is not recognised by most Buddhists; they use the term 'Bengali Muslims', a reference to the official view that they are illegal immigrants from Bangladesh.

Around 800,000 Rohingyas lack citizenship cards. Official discrimination has encouraged Buddhists to believe that they can justifiably campaign for their forced expulsion or segregation.

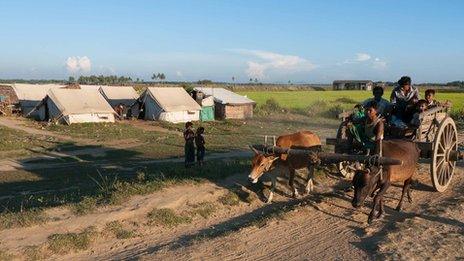

Displaced families are sheltering where they can, including in tents

'Mental separation'

Kyaw Hla Aung, a renowned Rohingya politician who spent more than 11 years as a political prisoner, laughs bitterly at these beliefs.

He was born in Rakhine, and spent most of his career as a lawyer, working in state courts, and now, at 73-years-old, collects a state pension. He showed me a document his father received in 1934 from the headmaster of a British-run school in what is now Rakhine.

Yet he is still officially viewed as an illegal immigrant. After the unrest in June he was arrested again, while working for the NGO Medecins Sans Frontieres.

The long decades of isolation and chronic injustice imposed by Burma's military rulers have left prejudice and resentment in Rakhine state to ferment into a poisonous climate of mistrust and misinformation.

Some Rakhine hark back to massacres in 1942, amid the chaos of the British withdrawal from the advancing Japanese imperial army. Back then Buddhist men often supported the Japanese-sponsored militia forces, while Rohingyas backed the British. Some go back even further, to the glorified memory of a powerful, independent Buddhist kingdom in Rakhine from the 15th to the 18th Century.

Along with the physical separation of Muslims and Buddhists, there is now a profound mental separation too.

- Published3 July 2014