Lahore roundabout sparks battle of identity in Pakistan

- Published

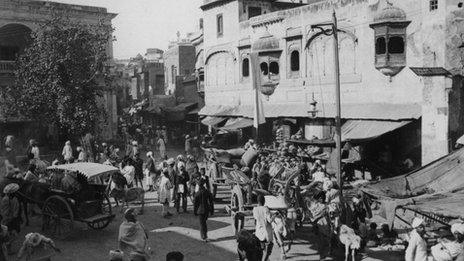

Lahore in 1912: The city has a long and rich tradition of cultural diversity

A row over the naming of an apparently mundane roundabout in Lahore exposed how much of a battleground Pakistan's identity can be. BBC Urdu's Shumaila Jaffrey examines the city's struggle to embrace its history.

Lahore has long been known for its historical traditions, love of culture and its diverse heritage, where parts of the city were named after Hindus, Christians, Sikhs and other communities.

That is now changing. Most roads and spaces have been renamed to be associated with Muslim heroes or personalities.

It appears as if nobody ever objected until the trend was bucked by the renaming of a small and insignificant roundabout, which stirred up a huge controversy between religious groups and civil society in the city.

In September, the district government of Lahore declared it would rename a roundabout called Fawara Chowk in the city's Shadman area after the revolutionary Indian freedom fighter Bhagat Singh in order to acknowledge his sacrifice for freedom.

Revered idol

Bhagat Singh was hanged in Shadman Square almost 80 years ago - when this part of the world was under colonial British rule - on charges of murdering a British police officer.

He is still one of the most revered idols of the Indian movement for freedom. For years, admirers of Bhagat Singh across the border in India have been imploring authorities to rename this square after him.

He was born into a Sikh family, but many historians believe he was an atheist. Irrespective of his religious views, his Sikh identity has become a bone of contention in the most recent controversy.

Several religious groups opposed the move.

The naming of this roundabout has created a storm in the city of Lahore

A spokesman for the hardline charity Jamaat-ud-Dawa, said: "We respect Bhagat Singh's sacrifices for freedom, but in the present age, the controversy is between Islam and non-Islam, and we believe that Islamic names, personalities and ideology should be promoted in Pakistan."

But the decision to rename the roundabout was approved - and it unleashed a torrent of opposition.

Religious groups said they would rename the roundabout Hurmat-e-Rasool (Sanctity of Prophet Muhammad) Chowk for themselves and threatened protests.

Now a local traders' association has filed a petition against the decision in the Lahore High Court.

In reality, most people do not care about its name but religious groups can bring pressure on people, particularly if they cast the move as anti-Islamic.

The trader who filed the petition, known simply as Zahid, said: "How can we tell our children such names, names that are associated with Sikhs? Hindus are demolishing our mosques [in India], and our rulers are naming squares after them!"

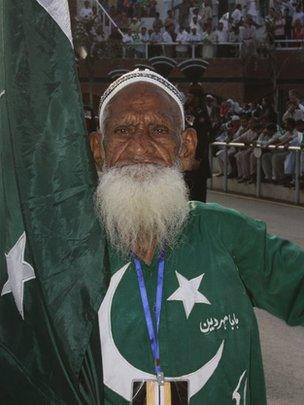

Chacha Pakistani was a patriot rather than a nationalist

There is little evidence to support the claim that mosques are being demolished in India, but such a message is likely to find supporters in Pakistan.

Although this is not the first time public amenities or monuments have been subject to dispute, it did raise many questions.

Is Pakistan a society that can embrace the long history of its land, including the events that shaped events in the sub-continent before Independence? Or is it a place that wants to shed all such past associations and focus on its current identity.

Queen Victoria moved

Under the British, there were many statues erected in public places. Many have since been removed.

One statue, of Sir Ganga Ram, noted for giving many landmarks to Lahore, was torn down in the communal riots of 1947 - retold in a short story by Urdu writer Hassan Manto - as documented in this blog post on Lahore's cultural heritage., external

"They first pelted the statue with stones; then smothered its face with coal tar. Then a man made a garland of old shoes climbed up to put it round the neck of the statue. The police arrived and opened fire. Among the injured were the fellow with the garland of old shoes. As he fell, the mob shouted: 'Let us rush him to Sir Ganga Ram Hospital.'"

Another prominent statue was Queen Victoria's which since 1904 had stood on Charing Cross Square on the Mall road until 1974 when it was removed from the public eye on the eve of the Islamic Summit Conference.

Since then it has been displayed at the Lahore museum. Statues of Dayal Singh, King Edward, Bhagat Singh, and Lord Lawrence met the same fate.

The prominent archaeologist, historian and the ex-director of the Lahore Museum, Saif-ur-Rehman Dar, believes that the statues were removed for religious reasons.

The statue of Queen Victoria can now be seen in the Lahore museum

"A very limited number of people are against pre-partition social and cultural icons, but they have access to media. They are very loud so their voices can be heard everywhere."

He adds that statues are not popular in Pakistan: "We don't have statue of Jinnah or Liaqat Ali Khan anywhere in the country as well."

But when it comes to home-grown symbols, there are fewer inhibitions.

Wagah cheerleader

Earlier this year, Mehar Din, also known as Chacha Pakistani (Uncle Pakistan), died aged 90. He was widely mourned in the city and indeed across the country.

With a distinctive white beard, for years he was regularly seen at Pakistan's Wagah border crossing with India holding a Pakistani flag and wearing colour-co-ordinated clothing as the famous ceremony was played out each day.

A patriot rather than a nationalist, he had become a prominent feature and could always be heard chanting pro-Pakistan slogans. The troops and visitors mourned his death and his zeal has been sorely missed.

"The Wagah border had become his home, and everybody here was his family," said one border guard, Asim. "As long as we remember, we cannot recall any evening when Chacha Pakistan was not around."

Bhagat Singh dedicated his life to revolutionary actions out of love for his motherland and these acts were part of the march towards independence from British rule. Chacha Pakistani lived from day-to-day to express his zeal for Pakistan.

But were it not for Hindus, Sikhs and others like Bhagat Singh who fought for independence from the British, the series of events that led to Pakistan's creation might never have occurred.

Lahore, meanwhile, remains divided about giving Bhagat Singh a place on its streets.

Mr Dar says: "History is continuity, individuals can accept or reject it on their personal liking and disliking - but it cannot be disowned."