Formidable power of Pakistan's anti-Shia militants

- Published

The key to the increasing power of these groups is not just their ideological fervour but also their ability to set up militant training camps

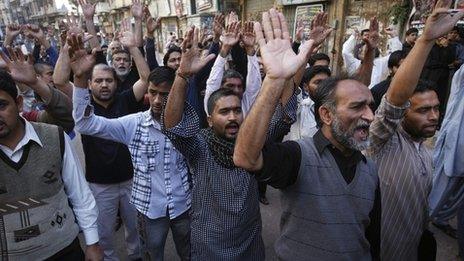

Wednesday's bombings of a Shia Muslim neighbourhood in the Pakistani city of Quetta that killed almost 100 people is a grim reminder of the power of sectarian militants to act as the arbiters of peace - and war - in this country.

Since 2004-05, they have steadily spread their wings in south western Balochistan province, where the ethnic Hazara community of Shia Muslims has been their main target.

Figures released by the Balochistan government place the number of Shias killed in the province between 2008 and 2012 at 758. Members of the Hazara community say the figure is much higher.

The hatred these Sunni militant groups bear towards Shia Muslims is fundamentally theological although the groups' origins date back to the late 1970s, the time of neighbouring Iran's Shia revolution.

The historic split between Sunni and Shia originate in a dispute soon after the death of the Prophet Muhammad over which of his four companions should lead the Muslim community.

The group which has claimed responsibility for the blast, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, was born out of another group called Sipah-e-Sahaba, whose name literally translates as "Soldiers of the Companions of the Prophet".

So their anti-Shia agenda is there in the very origins and name of this group. But over the last few years there has been a dramatic escalation on attacks against Shia Muslims around Pakistan, with some activists naming 2012 as the worst year in living memory for Shia killings.

The key to the increasing power of these groups to wreak havoc on Shias is not just their ideological fervour, but also their ability to set up militant training camps - and Pakistan's complex political environment.

Balochistan training camps

The bombing reflects the extent to which the Pakistani policy of using Islamic militancy as a foreign policy tool has, in the course of three decades, compromised its ability to clean up its house.

The geographical spread of these outfits today is unprecedented in terms of both their striking capability and their ability to paralyse life in areas of their influence.

In December, activists for Lashkar-e-Jhangvi, which is now banned, closed down Karachi, a city of more than 15 million people, when one of their leaders was injured in a gun attack blamed on a rival sect.

Credible reports from the region say the group has also set up several residential and training camps in the remote Mastung area of Balochistan, from where they have been attacking buses carrying Shia pilgrims to holy sites in Iran.

A couple of very large arms dumps uncovered by the police in Quetta in recent months indicate that they have copious supplies of arms, ammunition and explosives, and the tactics they use during attacks show them to be highly trained.

But sectarian militants also have vast influence in the north-western tribal region of Pakistan, where some analysts believe they form the backbone of the Pakistani Taliban group, Tehrik Taliban Pakistan (TTP).

Not many people know that some top TTP leaders - such as the late head of the suicide training squad, Qari Hussain, and the TTP's current spokesman, Ehsanullah Ehsan - were all members of Lashkar-e-Jhangvi in Punjab at one time or another before they became part of the TTP.

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and its affiliated groups also provide crucial technical and manpower support to other major groups in the tribal region, such as the Haqqani network and other groups.

Shia pilgrims are frequently targeted on buses by sectarian militants

Electoral power-brokers?

With this kind of spread and influence, can the sectarian militants be defeated at all?

Most analysts believe the state is far more powerful than the entire Pakistani militant network, but at the moment it lacks the will to pull the ground from under them.

There are various reasons for this.

In Punjab province, which is the breeding ground of sectarian militants, the Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and its parent organisation, Sipah-e-Sahaba Pakistan, have a strong electoral presence due mainly to the state patronage they enjoyed during the military regime of General Pervez Musharraf.

All the major political parties in the province depend on this vote bloc in many areas of central and southern Punjab to win parliamentary seats.

Therefore, any kind of a crackdown on these groups would run contrary to their interests, especially when elections are approaching.

The country's powerful military establishment also has an ambivalent attitude towards these groups. Even as cadres of these groups are clearly seen as an enemy because they work with the Taliban, they serve several other major interests.

Useful in a crisis

In Balochistan, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and its affiliates have helped dilute the impact of an armed nationalist separatist movement by diverting international attention to the issue of targeting Shias.

Elements in the military establishment have also felt a need to use the street protest power of these groups as a second line of defence at times of international crises.

Last year, these groups formed a major part of the movement launched by an alliance of Jihadist religious forces, the Defence of Pakistan Council, to put pressure on the Pakistani civilian rulers not to reopen the Nato supply routes through Pakistan.

In addition, these groups have provided both political and military support to Pakistani objectives against India in the disputed region of Kashmir.

As things stand, the Afghan endgame, in which the Pakistanis are fishing for a major role, is yet to play out to the finish, and the border with India in Kashmir is far from stable.

So while the destructive potential of these groups is not lost on anyone in Pakistan, they have not outlived their utility quite yet.

And if they continue to prove their anti-Shia credentials day after day, they will not have lost their utility for the Sunni-Wahabi sheikhdoms of the Middle East as well, from where they receive the bulk of their funding.

- Published11 January 2013