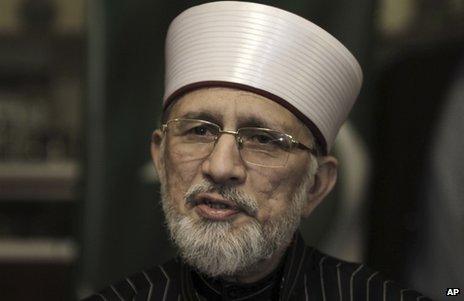

Tahirul Qadri - Pakistan's latest political 'drone'?

- Published

Qadri's role stirs unease - Pakistanis wait to see if he moves centre stage or into political oblivion

A prime-time ad on the electronic media in Pakistan these days shows Dr Tahirul Qadri, a Canada-based Islamic scholar of Pakistani origin, goading the public into joining his "long march" on the capital Islamabad on Monday.

"If you fail to come out, if you fail to strengthen my arms, then [future] generations will rue this day," he thunders in his typical furious style as the star and crescent of the green Pakistani flag flutters in the background.

Last month, Mr Qadri descended on Pakistan rather suddenly, nearly seven years after he moved his hearth and home to Canada.

His arrival was heralded by another expensive television ad campaign touting the slogan "save the state, not your politics" - an apparent broadside at the major political forces who are readying for elections due in May.

The campaign promised a long march on Islamabad to achieve two objectives: get rid of the "corrupt" government and pave the way for electoral reforms under an interim government of "honest" people.

For many, the message was clear - derail the democratic system on the pretext of cleaning up the mess, an exercise which the country's military has conducted several times in Pakistan's brief history.

His subsequent stress on a role for both the military and the judiciary in choosing an interim government has sparked rumours that he probably had the backing of the military establishment.

Fringe player

Soon afterwards, on 23 December, he addressed what many observers here describe as a huge political rally at Minar-e-Pakistan, the independence monument in Lahore city, indicating that he had the street power to destabilise Islamabad.

This threat was magnified when the Karachi-based MQM party threw its weight behind him, declaring in another public meeting on 1 January that it would participate in the long march.

But can Mr Qadri sustain the momentum?

A law graduate from the University of Punjab, Mr Qadri has waded in many waters during his career. He established himself as an academic, an Islamic scholar and orator, a charity worker, a politician and a parliamentarian.

But at no point has he been able to graduate from a fringe player to a charismatic leader of the masses - something which his critics say he is still trying to achieve.

Since the 1980s, he has travelled extensively around the world, delivering lectures and organising communities under the banner of his Minhajul Quran International, an educational and charity network he founded in 1981.

He launched a political party in 1989 but was able to win a parliamentary seat only in the 2002 elections that were widely seen as tailored by the then military ruler, Gen Pervez Musharraf, to suit his own political aims.

After memo-gate

Since 2005, he has been living in Canada from where he says he can better manage his global network that, he says, extends to more than 80 countries.

In the West, he did manage to be taken seriously by some circles, due mainly to his unorthodox views on religion, his stress on inter-faith harmony and his support for democracy.

But many in Pakistan liken his sudden return to the country as a drone that is out to upset the country's nascent democracy.

At least in the initial days after his arrival, he appeared to pose the most serious threat to the system since the "memo-gate" affair - a dubious scandal built around a controversial Pakistani memo that allegedly requested American intervention to cut the Pakistani military down to size.

The scandal, which broke in late 2011, caused both the judiciary and the military to menacingly gang up on the civilian government but dissipated when some of the ensuing criticism started to turn against these two institutions.

Ebbing support

Like memo-gate, Mr Qadri too has come in for widespread criticism over his motive to strike at a time when the elections are just four months away, and over the sources of his funds.

Qadri says he has massive appeal

He has been dismissed as an "agent of anti-Pakistan and anti-democracy forces" by almost all the political parties, secular as well as religious.

The storm of speculation forced the army spokesman, and even the US ambassador in Islamabad, to deny any association of the military or the US with Mr Qadri's campaign.

Last week, Mr Qadri's only political ally, the MQM, announced it would pull out of the march, leaving him completely isolated.

But he continues to press on with the march, which analysts say may end up in one of two scenarios.

First, he manages to press the "pause" button on democracy. This scenario presupposes that he can paralyse Islamabad for several days running, or a bloody attack of some sort takes place, and the military is willing to use this mayhem as a pretext to force a change of government.

Second, he gradually slides back off the centre-stage and passes into oblivion, like so many before him in this country of underhand deals and palace intrigues.

- Published23 December 2013

- Published15 March 2024