'Bulldozer of news' tests Pakistan's resilience

- Published

Pro-democracy demonstrators gathered in Lahore to demand the resignation of the government

With just four months until elections, a resurgence of sectarian violence in Pakistan is testing the country's resilience.

A colleague, newly arrived in Pakistan, summed up the situation after her first week here.

"It is like living beneath a bulldozer," she said, "that keeps heaping more news on top of you."

So far this month we have had a devastating attack by Sunni militant extremists, a dangerous escalation in tension with Pakistan's nuclear neighbour, India, and a mass protest within sight of parliament.

Elsewhere that might suggest a country on the brink of collapse. Here it is, more or less, situation normal.

Last week's chaos came in the form of tens of thousands of demonstrators, demanding the resignation of the government.

They streamed into Islamabad in a flag-waving convoy of motorbikes, cars and buses - a human tidal wave of discontent, armed with blankets, plastic sheeting, and a mobile dispensary.

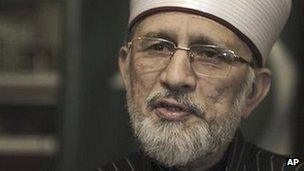

Their leader was Tahirul Qadri, a charismatic Muslim cleric, who reappeared from Canada just last month.

The white-bearded preacher rallied his faithful with fiery speeches. But he did not get too close - broadcasting to the masses from inside a bomb-proof container.

Hour after hour he denounced Pakistan's leaders as inept, corrupt, thieves. His followers responded with chants of "we want change".

Among them we found doctors, labourers, entrepreneurs and the unemployed. They complained about shortages of electricity and gas, about the lack of jobs, and the need to pay bribes.

On day four of the protest, the sky darkened with rain and the cleric's promised revolution turned into a damp squib. Tahirul Qadri secured a few minor concessions from the government, then sent the crowds home.

Mr Qadri, an Islamic law expert, once sat in the Pakistani parliament

The peaceful end of the protest was seen by many as a victory for the government, whatever its faults.

But there are lingering concerns that the cleric was a mouthpiece for Pakistan's powerful military leadership. It has a habit of playing politics.

In all this chaos some see proof of the country's resilience, as well as its many fractures. Over dinner in Islamabad, a retired general with a moderate outlook, predicted Pakistan could turn a corner with the upcoming elections, due in May.

If all goes to plan this would be the first time an elected government here hands power to another.

"I am older than Pakistan," he said with a smile, "and I believe this election could be the start of a change. It will take time but our fragile democracy could get a bit stronger."

If so it will come too late for the dead of Quetta. Around 100 people were killed on 10 January in a sectarian attack by Sunni extremists. They want to wipe out members of the Shia minority, who they see as heretics.

One of the victims was a human rights activist called Irfan Ali. He was Shia, but he campaigned for all those who are persecuted. On his Twitter profile he described his faith as one of "respect, and love for all religions".

That morning Irfan cheated death. The 37-year-old, with the curly hair and the broad smile, was near the scene of a bomb attack in a market place.

He made it home safely and tweeted about narrowly missing the blast that killed 11 people. But that night death came calling again.

Irfan was at home with his mother and younger brother Mohammed. As they chatted he gave Mohammed some advice.

"He told me that here in Pakistan there is no law and no justice," said Mohammed. "He told me, 'I must try to help people and bring understanding between different groups.'"

Then they heard a bomb go off.

Irfan did what he always did - he rushed to help those in need. The blast was at the Star Snooker Club nearby. It had been crowded for a big game.

Ifran Ali was killed in an attack that had been specifically planned to target rescuers and police

"The last time I saw him he was putting dead bodies in an ambulance," Mohammed told me. "I said 'you should go home and get a coat because it is cold'. He said 'I do not need to go home. I am here to help people.' Those were his last words."

Seconds later Irfan was gone. He was killed in yet another massive explosion, timed to target the rescuers and police who had rushed to the scene. His brother-in-law, Zahid, died with him.

The country Irfan left behind is plagued by Taliban suicide bombers and sectarian death squads, by economic hardship and political uncertainty.

Having lived here for three-and-a-half years, I know Pakistan is resilient, but so are the extremists who want to steal the future.

Mohammed says he hopes to continue with the work of the brother he loved, but then he tells me he also hopes to leave the country.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent, external:

BBC Radio 4: Saturdays at 11:30 and some Thursdays at 11:00

Listen online or download the podcast.

BBC World Service: Short editions Monday-Friday - see World Service programme schedule.

- Published23 December 2013

- Published11 January 2013

- Published15 March 2024