Afghanistan's security prospects after Nato withdrawal

- Published

Frank Gardner talks to former Afghan Intelligence Chief Amrullah Saleh

Nato-led forces have been in Afghanistan for so long now that it is almost hard to remember why they went in.

Governments often repeat that it was in direct response to Al-Qaeda's attacks of 9/11, planned from Osama Bin Laden's Afghan base.

But that does not explain why now, more than 11 years later, there are still more than 100,000 troops from 51 countries stationed in this country and yet they have failed to defeat the insurgency that kills and maims on a daily basis.

By the end of next year Nato's combat forces will all be gone, leaving Afghanistan's national security forces to fight a determined enemy on their own.

Can they do it?

Traffic police attacked

Through the veils of sleep I became dimly aware of sirens outside my window.

There was shouting, megaphones and the rush of fire engines racing down the street.

The attack on the traffic police was the second brazen attack on this scale in the capital in a month

It was my first morning back in Kabul and a team of jihadist insurgents had targeted the capital's traffic police headquarters, detonating suicide vests, then holding out inside for nine hours in a protracted gun battle before being killed.

It was the second brazen attack on this scale in the capital in less than a month. Later, I learned there are, on average, four such planned attacks here every week that get foiled, mostly by the national intelligence service, the NDS.

Even that agency's chief has become a victim, recovering in a US hospital from a recent failed assassination attempt and issuing orders by phone from several thousand miles away.

One of his predecessors, Amrullah Saleh, who led the NDS's intelligence war on the Taliban from 2004 to 2010, told me he expects such attacks to increase.

"As Nato withdraws forces and reduces its presence in Afghanistan, the Taliban are going to change their tactics," he said.

"They're going to modify their strategy and they are going to do more and more spectacular attacks.

"Why? Currently they are having this two track strategy: a very slow, frustrating, with no tangible results - talks with Americans and episodically and at very low level with Afghan government," Mr Saleh said.

Parallel with that, he added, what gives the Taliban integrity and cohesion "is fighting".

"The moment they stop fighting that integrity and cohesion will fracture, and they know it," he said.

Attacks 'for show'

But what about those peace talks? Aren't the Taliban supposed to be exhausted after years of war, and aren't they now poised to open an office for political dialogue in neutral Qatar?

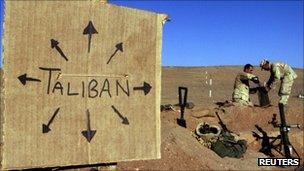

Western forces have been unable to destroy militant infrastructures

One of Afghan President Hamid Karzai's leading interlocutors is Mohammed Stanekzai.

Just back from preliminary talks in the Gulf, I went to see him in his well-guarded office. Noticeably older, greyer and more weary than when I last saw him a few years ago, he insisted there was hope for peace.

These recent attacks in Kabul, he said, were for show. I pressed him on who he thought was behind them and why.

He said: "Whether they are criminals; whether they are Taleban; whether they are al-Qaeda? If you do a deeper analysis, most of those suicide bombers are not Afghans."

Minister Stanekzai, as everyone addresses him, is head of the Afghan Peace and Reintegration Programme, the APRP. (A by-product of having Nato here for so long is that the country is now awash with acronyms.)

For two years now, it has been reaching out to low-level insurgents and trying to entice them to lay down their weapons and rejoin village communities.

It has had limited results: just 6,028 have officially joined the programme across the whole country. That is compared to an estimated 30,000 Taliban insurgents who seem to have an inexhaustible supply of new recruits from their bases across the border in Pakistan.

Important for enemies

I asked to see the programme in action, so on a bright, sub-zero morning I accompanied a government delegation to the troubled province of Ghazni, taking off from a frozen landing site at the Nato base in Kabul in a US Army Chinook helicopter.

Some think the West's haste to leave Afghanistan is making it downplay the Taliban threat

With the tailgate open, the breath-taking beauty of snowbound Afghanistan unfolded beneath us, the landscape stark, brittle and largely empty.

In Ghazni the Taliban have a strong presence, so to get from the local base to the Governor's office we had to squeeze into heavily armoured mine-resistant vehicles called Cougars.

As the convoy growled down Highway One, the national ring road that encircles the whole country, the turret machine-gunner rotated left and right, scanning the roadside.

"Our president always says that if Ghazni is safe, the whole of Afghanistan is safe" the governor, Musa Khan, told me later. "Ghazni is important both for our enemies and its very important for us".

But Ghazni is not safe. As I sat in the Governor's office for a shura, a mini-conference of tribal elders, I heard a distant thump.

Nobody flinched but it turned out to be the sound of a suicide bomber blowing up a police checkpoint in town, killing three.

Job-seekers or Taliban?

Little wonder the US soldiers escorting the delegation were nervous.

Across the street, we found two dozen Afghan men we were told were former insurgents who had been persuaded to give up the fight and were now being "enrolled" into the programme.

In exchange for turning in their Kalashnikovs, they would each be given up to $180 (£115) a month for a limited period as they assimilated back into village life.

It was impossible to know how genuine they were.

"The people in this programme are not real Taliban," scoffed Afghans I had met in Kabul. "They are just job-seekers."

But still, I noticed the men kept their faces covered by their scarves, they seemed extremely wary and after a brief and rather uninformative interview with their "commander", a local official whispered to me: "This is a very bad man: he has done bad things".

It was hard to assess the reintegration programme.

More dangerous

Of course, as a journalist, it can sometimes be all too easy to fly into a country and pick holes in other people's efforts.

Back in the capital, I remarked to Lt Gen Nick Carter, the senior British general and deputy commander of all Nato's forces in Afghanistan, that despite its bustling street life the city seemed edgier and more dangerous than when I had first visited in 2003.

Afghanistan feels more dangerous now than it did 10 years ago

There are far more blast walls and checkpoints than before. I put it to the general that most people don't understand why Nato has not finished the job and gone home by now after so long here.

Gen Carter, a veteran of several senior command postings in Afghanistan, did not deny it was more dangerous now than 10 years ago. "But it's remarkable how things have progressed in the broader civil society sense," he countered.

"Access to healthcare is very different to what it was; education has moved on hugely. There are 20 million mobile telephone users now.

"I think in terms of the sort of progress towards the sort of things that we would understand in our countries there's been a momentum which is, I wouldn't say irreversible, but it's progressed in an extraordinary way."

But Amrullah Saleh, the long-time Afghan intelligence chief who handed over running the NDS in 2010 and who is now a political opponent of the president, has a warning for the West.

He believes that in its haste to exit Afghanistan, the West is so eager to differentiate between the Taliban threat and that of al-Qaeda that it is downplaying what he sees as the dangers of a Taliban return.

The security forces are expected to control main towns and cities after 2014

"A lot of Western analysts now say al-Qaeda's main base is no longer Afghanistan; it's maybe Mali, it's maybe Somalia, it's maybe North Africa," he said.

"Or maybe it's a sleeping cell in some corner of Europe so why we should have massive force here?"

But he disagrees with part of that analysis, saying al-Qaeda's objective was to franchise, and they have franchised.

"And if Afghanistan remains unresolved, so this will become, even if not realistically but psychologically, with domination of Taleban, it means an ally of al-Qaeda re-dominating the country, whether partly or wholly," Mr Saleh said.

"The current effort to underestimate the strength of the Taliban, to try to delink them from al-Qaeda in our own imaginations is wrong," he added.

Others in Afghanistan disagree.

They say the Taliban have learned from their mistakes and know that so much has changed since they were last in power that there are some things they could never bring back, like banning televisions or burning down girls' schools.

Either way, Afghans are truly tired of war, after 33 years of constant conflict, but the search for a peace deal could still prove to be a long and costly one.