North Korea nuclear test raises uranium concerns

- Published

Experts are waiting for evidence of any gas leaks from the North Korean test site to find out if uranium was used in the explosion

North Korea's third nuclear test - following on from two earlier explosions in 2006 and 2009 - inevitably raises all sorts of questions about the country's nuclear capabilities. In due course it may provide some answers.

Much will depend upon the analysis of data recorded at the time of the explosion. The exact size of the blast is still unclear.

James Acton of the Carnegie Endowment in Washington DC told me: "The geology of the test site is not well understood. It will take a lot of seismic analysis to get a good figure."

His initial "back of an envelope" calculation suggests a yield of between four and 15 kilotons. "In short," he argues, "all early yield estimates should be treated with caution."

The size of the blast is one thing, but the exact nature of the device exploded is quite another. This matters.

'Game-changer'

North Korea's first two nuclear tests are believed to have been plutonium-based devices. But there has been active speculation amongst experts that this latest test might involve a device based upon uranium.

Determining this will depend upon the identification of any leakage of gases during the test itself.

Mark Fitzpatrick, Director of the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Programme at the London-based International Institute for Strategic Studies, suggests that one tell-tale sign that this might be a highly-enriched uranium (HEU) device would be the detection of xenon or other noble gases in the atmosphere.

James Acton says "there is a significant chance that there will be leakage of gases, but there is no guarantee that material will be detected". There were leaks after Pyongyang's first nuclear test, he notes, but none were detected after the second.

A device based upon highly-enriched uranium would be a very significant development.

As Mark Hibbs, also of the Carnegie, notes: "In the past North Korea had no choice but to deplete its small and finite inventory of plutonium to test nuclear weapons.

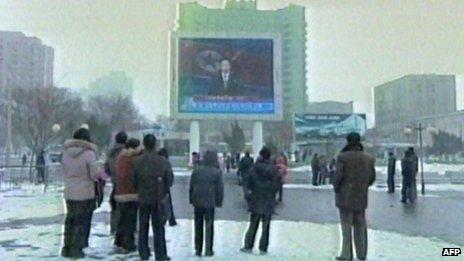

Leaders and demonstrators in South Korea and Japan condemn North Korea's actions

"Today and in the future," he says, "an unchecked and growing enrichment capability in North Korea is a game-changer because it will allow Pyongyang to indefinitely stockpile highly-enriched uranium fuel for an ever-larger nuclear weapons arsenal."

Mark Fitzpatrick argues that if Pyongyang has perfected the highly-enriched-uranium route to a bomb, then there will be heightened concern about the potential for the proliferation of these weapons or materials.

"HEU can be more readily fashioned into crude nuclear weapons by terrorists and other non-state groups," he points out.

Of course, Pyongyang's nuclear and missile programmes must be viewed in tandem.

There is no point in developing a working nuclear device if it cannot be weaponised - in other words, turned into a functioning bomb that can actually be delivered to a target. That too could be what this test is all about.

North Korea's ambitious long-range missile programme is seen as the obvious delivery system for such a weapon.

But a nuclear warhead would have to be small enough to fit onto, say, a Nodong missile - and it would have to be capable of withstanding the buffeting and other forces exerted on it during flight.

The forensic investigation of this nuclear test is only just getting underway. Data may be limited. But the potential is there to discern vital clues about Pyongyang's secretive nuclear programme.