Why Afghanistan may never eradicate opium

- Published

The high price of opium has led many farmers back to poppy cultivation

Despite the best efforts of Afghanistan's drug eradication programme, the BBC has learned that farmers in several Afghan provinces, which had been deemed poppy-free, have gone back to cultivating opium poppies.

For years Afghanistan has been the world's largest producer of opium, the raw material for heroin, most of which is exported to Iran, Russia and Europe.

Programmes by the Nato-led Isaf force, the Afghan government and the UN to entice farmers away from cultivating the flower met with some success.

But farmers say that the high sale price of opium is difficult for them to resist.

They have another gripe: although the Afghan government and the international community initiated opium eradication programmes, many farmers say promises to provide high-quality seeds and fertiliser, carry out developmental projects and promote alternative careers have not been kept.

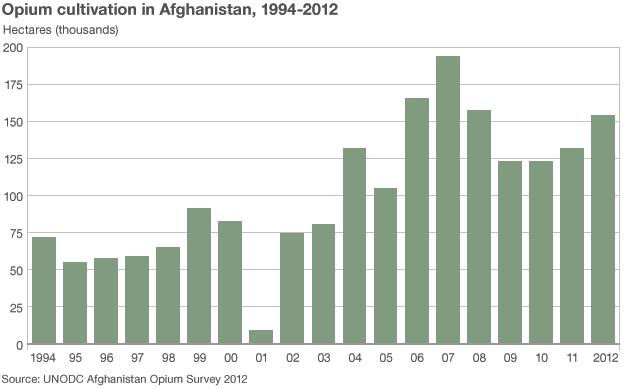

And despite an aggressive campaign to destroy the crop, the total area under poppy cultivation increased by 18% in 2012, reaching 154,000 hectares (380,000 acres), compared with 131,000 hectares in 2011, according to a 2012 United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) report and Afghan officials.

One piece of apparently good news from that report was that the overall production of opium decreased by 36% - from nearly 6,000 tonnes in 2011 to around 3,700 tonnes in 2012.

But experts say this was due to a lower yield caused by plant disease and adverse weather conditions in several parts of the country.

Better income

A common complaint from Afghan farmers is that traditional crops, grown legally, do not bring them enough money.

"If we cultivate wheat, it might give us just bread. But what about clothes, medical costs and other things?" says Gul Ahmad, a farmer in Helmand province's Nad Ali district.

"Cultivating wheat will not even cover the cost of the fuel needed to pump out underground water."

A number of farmers who have switched to traditional crops such as cotton complain the prices of these crops have fallen and that there is no market for them at home or abroad.

"I cultivated cotton last year, but the prices are half of what they were last year," says Nuruddin, a farmer in the Chamtal district of northern Balkh province.

The Afghan government estimates that in 2011, the livelihoods of some 191,500 rural households depended on the growing of illicit drug crops, primarily opium poppy.

Among the surveyed villages, however, only 30% had received some form of agricultural assistance (eg seeds, fertilisers and irrigation) in the preceding year, says the UNODC 2012 report.

As part of its counter-narcotics strategy, the Afghan government has started a "Food Zone Programme" led by provincial governors, which also includes schemes to help farmers with seeds and fertilisers.

But provincial governors usually complain that they don't get enough funds from the international community to help farmers properly and fulfil the promises they made to them.

"I have a small piece of land which is my only source of income. If I cultivated other crops, it wouldn't bring me enough money to feed my family for a year," says Rahman Gul, a farmer in the eastern province of Nangarhar, which was poppy-free in 2008, but later lost this status.

Over the past few years, opium poppy cultivation has moved between and within provinces. In some cases this has meant the destruction of drug crops in one area simply leading to cultivation moving elsewhere.

The government has run aggressive poppy eradication programmes

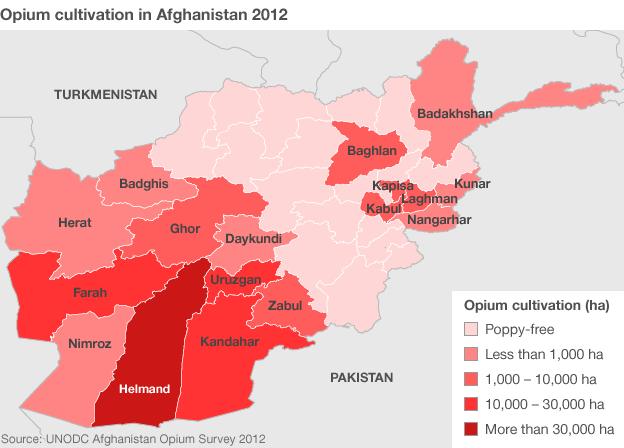

According to the latest official figures, 17 of Afghanistan's 34 provinces had fewer than 100 hectares dedicated to opium cultivation and so were considered to be poppy-free.

But even this status is a movable feast: western Ghor province lost its poppy-free status in 2012, while northern Faryab province regained its poppy-free status.

Sometimes, farmers leave poppy cultivation when they are under pressure from the government, or when they are convinced by the promises of aid and developmental projects; some later return when the alternatives are not as lucrative or if government control weakens.

Cannabis and saffron

In the officially poppy-free province of Balkh a number of farmers switched back to poppy cultivation in at least two districts: Chamtal and Chaharbolak.

"I haven't cultivated poppies over the past two years, but no-one has given me any seeds or any other help," says Mawladad in Chamtal district.

"We all cultivated cotton last year, but there is no market and it is all stored in our houses."

The Afghan government does not readily accept this interpretation of events. It ran an aggressive campaign in 2012 taking poppy eradication to unprecedented levels, destroying nearly 10,000 hectares of poppy fields.

"We don't have a report that poppy has been cultivated on a large scale," says Rahim Rahman Oghly, the provincial head of the counter-narcotics department in Balkh.

"Last year, some farmers cultivated poppies in remote and insecure areas, but we destroyed their fields."

However, the cultivation of cannabis has replaced poppies in some parts of the country including Balkh province. Revenues from cannabis cultivation and production of cannabis resin are similar to or even surpassing those earned from the cultivation of opium poppy.

In recent years, many farmers in a number of provinces did start cultivating saffron.

"We have been cultivating saffron for the past two years which brings us the same amount of money as poppy," says Rahmatullah, a farmer in Kandahar province's Daman district.

"The government should find markets for our legal produce."

Risky affair

The UN and Afghan government figures show that the vast majority (95%) of poppy cultivation took place in the nine most insecure provinces in the country's west and south in 2012.

Southern Helmand province, where thousands of British and US troops are based, remained the largest opium-cultivating province in the country with nearly half of the country's total cultivation.

The Taliban banned opium poppies in the summer of 2000. But after it was toppled by a US-led invasion in 2001, the militant group reportedly encouraged some farmers to cultivate drugs and offered them protection.

Afghan officials say the Taliban insurgents get more than $100m (£65m) annually from taxing farmers and drug producers in areas of the country they control.

This means that even eradication is becoming risky. Official figures show that 102 Afghan soldiers, police officers and civilians died from attacks by farmers, drug traffickers and Taliban insurgents during the 2012 poppy eradication campaign, while another 127 people were injured.

Some farmers resort to violence to protect their poppy fields from destruction, saying they cannot allow the government to take away from them the only means of income they have.

"We are poor and desperate. If the government cannot help us by providing aid and jobs, then it shouldn't harm us either by destroying our fields," says Haji Munib, a farmer from Nangarhar province's Sherzad district.

The international community's engagement in Afghanistan is winding down, but analysts believe the issue of drug production is likely to remain an acute problem for decades to come.