Viewpoint: What is driving North Korea's threats?

- Published

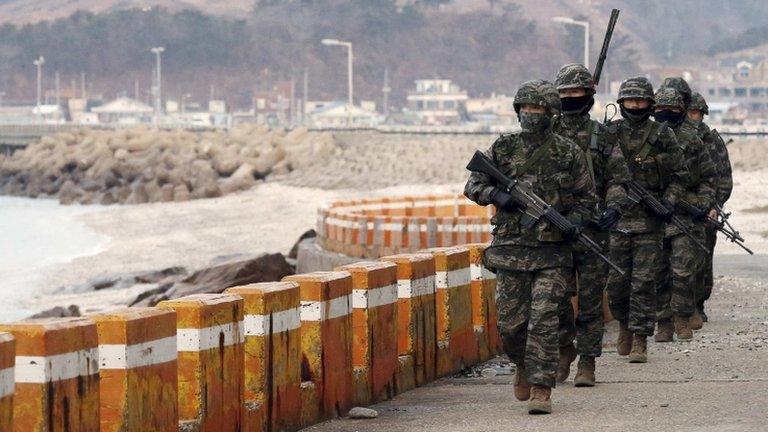

North Korea's drills have matched its fiery rhetoric in recent days

More than 40,000 US and South Korean troops are currently conducting military manoeuvres on the Korean Peninsula, as part of the annual Foal Eagle exercise.

US bombers, fighter aircraft and submarines have made their way to the region in an effort to "enhance the security and readiness" of South Korea.

Those exercises are seen as a visible way for Washington to reassure Seoul of the reliability of its alliance and extended deterrence commitment.

North Korea allegedly reads the purpose of these exercises differently, claiming that they could be a cover for preparations for a surprise attack. In response, Pyongyang has drawn on the tool most familiar to it: fiery threats of escalation.

Words of war

International coverage of tensions with North Korea creates the impression that their recent threats in response to military exercises come out of the blue. In fact, Pyongyang has loudly objected to joint manoeuvres for decades.

Where North Korea's latest threats diverge from past practice is in their intensity and specificity.

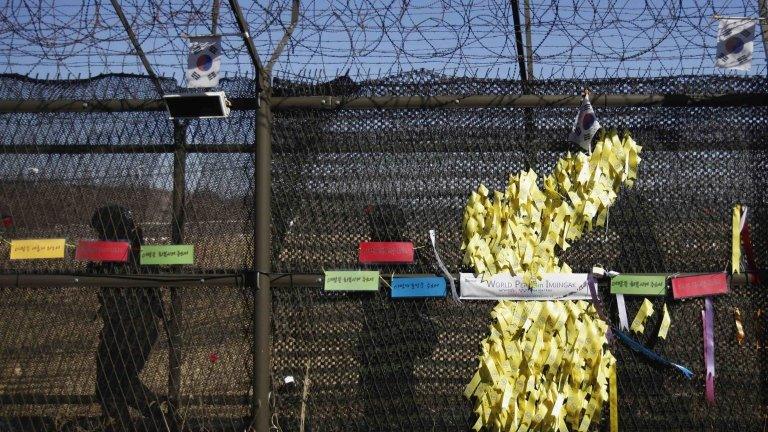

Over the last month, Pyongyang promised to shred the 1953 armistice agreement and shut off the hotline at the border region. It then announced it had increased the combat-readiness level of its artillery forces, with targeting that it claimed would put US bases in Guam and Hawaii in the crosshairs.

Kim Jong-un has made multiple visits to military units amid the tensions on the peninsula

Most audacious was Pyongyang's announcement that it reserves the right of pre-emptive nuclear war against Washington or Seoul.

Though Pyongyang has followed through on cutting off the hotline at Panmunjom, there is little reason to suspect that it will deliver on some of its other promises, at least anytime soon.

One reason for this is that a major audience for Kim Jong-un's tough talk is domestic. The young leader was promoted quickly through the ranks of the Korean People's Army by his late father, despite having done little to earn those qualifications. Standing up to North Korea's enemies will help Kim Jong-un consolidate his military and political power.

A second cause for temporary calm is North Korea's technological shortcomings in the nuclear and missile fields.

Most analysts agree that it is unlikely that Pyongyang has successfully mastered the technology needed to get a nuclear warhead atop a ballistic missile and deliver it to Washington - yet.

However, its recent missile launch and nuclear test demonstrate that North Korea is eager to advance its capabilities in that direction.

Fear of military exercises

While we may repudiate Pyongyang's threats and their specific formulation as largely domestically-directed bluster, it is possible that North Korea's underlying insecurities are sincere.

Concerns that military exercises could be used as a veil to prepare a surprise attack on North Korea seem incomprehensible from a Western standpoint. "War games" are just that, and their political value in reassuring a nervous South Korea is an important added political benefit.

But North Korea, which thinks in "military-first" terms and prioritises self-reliance in its affairs, may be sceptical that joint exercises are just about readiness to respond to attack or benignly demonstrating an alliance commitment to South Korea.

Possibly cementing North Korea's divergent interpretation is the fact that in 1950, Pyongyang itself used exercises for the malign purpose it now sees in Foal Eagle.

In June 1950, Pyongyang put in place a plan that concealed large-scale military movement towards the 38th parallel under the guise of training exercises. In the midst of these war games, several participating divisions headed south for Seoul, triggering the Korean War.

Previous US administrations have tacitly acknowledged that the gap in understanding between Washington and Pyongyang about the purpose of military manoeuvres is vast.

Risking miscalculation

President Clinton repeatedly cancelled the annual Team Spirit exercises to quell Pyongyang's worries and incentivise negotiations on its nuclear programme.

At present, the risk is not one of large-scale war or nuclear attack, but one of miscalculation.

North Korea bitterly opposes the annual US-South Korea military drills

North Korea continues to search for new ways to issue threats - partly in an attempt by the regime to consolidate power at home, and partly in the hope that the US cancels its exercises as President Clinton did. As Pyongyang does so, the West calls their bluff and continues to carry out drills and B-52 flights over the peninsula.

This concerning pattern occurs in the absence of any regular engagement between the US and North Korea. Should it persist, the risk of miscalculation by either side will rise.

North Korea could read a future US move incorrectly and determine that an imminent and existential threat to the regime exists - then choose to pre-empt it. Or, if too many of its bluffs are called, Pyongyang may feel that its rhetoric no longer deters. It may decide that more aggressive action is needed to match its words.

One test of the sincerity of North Korean fears over military manoeuvres will be to gauge the regime's rhetoric once exercises conclude in late April.

Ways out of the current situation are limited. Talks between Washington and Pyongyang are unlikely to convince North Korea to forfeit its nuclear programme.

But dialogue on Korean peninsula security, including the issue of military exercises, could help prevent further misunderstanding and miscalculation. It could ensure North Korea hears not just the strong messages of alliance security tailored for Seoul.

Washington should also be cautious with any subsequent efforts to visibly reassure allies which might counter-productively exacerbate North Korea's potential insecurities. Moves such as keeping nuclear-capable military assets in the region could unnecessarily prolong the risk of miscalculation after the Foal Eagle exercises end.

Andrea Berger is a research fellow in nuclear analysis at the Royal United Services Institute. Follow her on Twitter @AndreaRBerger.

- Published14 March 2013

- Published12 March 2013

- Published11 March 2013

- Published15 September 2015

- Published11 March 2013

- Published8 March 2013