Yongbyon restart: North Korea ramps up nuclear tension

- Published

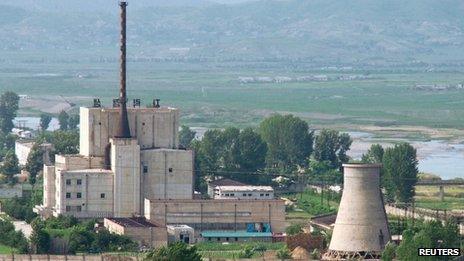

North Korea demolished Yongbyon's cooling tower (right) in 2008, but the status of its enrichment programme is less clear

Among Pyongyang's recent inflated threats, the announced intention to "readjust and restart" its nuclear facilities is the most worrisome.

If implemented, North Korea will be producing both kinds of fissile material that can create nuclear explosions: plutonium and highly enriched uranium.

The handful of nuclear weapons - from four to 10 - that North Korea presumably already possesses are based on plutonium that was produced at the small 5MW reactor at Yongbyon prior to mid-2007.

Whether it also has uranium weapons is unknown.

Why North Korea abandoned the plutonium program and instead prioritised uranium enrichment has been a mystery.

There are two presumed reasons:

Enrichment facilities are easier to hide - North Korea certainly has more than the one enrichment plant it revealed in 2010

Some kinds of uranium weapons are easier to build, and North Korea probably obtained a uranium-weapons design from the Pakistan-based AQ Khan black market network, which also sold the designs to Libya and Iran.

But why has North Korea not restarted the plutonium programme during the past several years when it has taken so many other provocative steps in the nuclear and missile areas?

Other facilities

One cannot rule out the possibility that six years of idleness have rendered the reactor inoperable.

Yet Stanford University nuclear scientist Siegfried Hecker reported in 2010 that the reactor was being maintained, external.

His judgement that six months would be required for re-start is probably still correct.

A new cooling tower or an alternative cooling system would have to be built and a fresh fuel load would have to be prepared by resizing and cladding a stash of fuel rods that were prepared many years ago for a different reactor project.

It is conceivable that, out of sight of prying satellites, North Korea has already refashioned the fuel rods, but work on the cooling system would be observable and no such unusual activity has been reported.

The status of the enrichment programme is less clear.

When Hecker was shown a 2,000-centrifuge plant in November 2010, he could not tell if it was operating at all, let alone producing low-enriched uranium for fuel purposes, as claimed.

Pyongyang's latest announcement might mean that the facility will now be used to produce highly enriched uranium, although it is widely assumed that North Korea already has other facilities for that purpose.

The new element in the announcement is North Korea's acknowledgement that the uranium enrichment is for weapons use.

Until now, Pyongyang had clung to the transparent fiction that it only had a peaceful rationale.

If the latest threats are carried out, the plutonium and uranium enrichment programs could each produce one or two weapons' worth of fissile material a year, and maybe more, depending on the size of hidden enrichment plants.

There could be worse to come.

No good solutions

The prototype light-water reactor that North Korea is constructing at Yongbyon, and which requires enriched-uranium fuel, could add to the fissile material stockpile when it is completed, possibly by the end of the year.

That reactor type is not ideal for producing weapons-grade plutonium, but all reactors produce plutonium that could be used in a nuclear explosion.

Seoul correspondent Lucy Williamson: "Most people believe North Korea does not want to provoke an all-out war"

The UN sanctions on North Korea and the tighter measures adopted by the US, EU and several other countries are designed in part to stem the flow of materials and components for North Korea's strategic weapons programmes.

Given China's inattention to implementation, the sanctions are leaky at best.

In any case, North Korea is by now self-sufficient in most aspects of its nuclear programme.

Unless the 5MW reactor has rusted out, it can be brought into line without any foreign assistance.

Unfortunately, there are no good solutions.

The only glimmer of hope is that North Korea also announced that along with the nuclear weapons work it will simultaneously be pushing forward economic development.

The latter, however, precludes any of the foreign trade and aid that will be required if North Korea is to escape its poverty.

If leader Kim Jong-un learned anything from his youthful years in Switzerland, let us hope that he picked up something about economics.

Mark Fitzpatrick is the director of the Non-Proliferation and Disarmament Programme at the International Institute for Strategic Studies