Pakistan election: Taliban threats hamper secular campaign

- Published

Opposition leader Nawaz Sharif has held a number of major rallies

The cancellation of a key political rally that was to kick-start the election campaign of one of the largest political parties in Pakistan is seen by many as indicative of hard times for the country's secular political forces in the coming days.

The Pakistan People's Party (PPP) abandoned plans for Wednesday night's rally in its native stronghold of Larkana town following what party leaders called "security threats" from militants.

The PPP is one of three parties recently named by a spokesman of the Pakistani Taliban as "legitimate" targets for militant attacks during the elections, due in May.

The other two parties on the hit list are the Karachi-based MQM, and the Pashtun nationalist ANP party which has its main base in the north-western province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP) and also enjoys sizeable support in Karachi.

All three are professedly secular, and were partners in the government that completed its five-year term last month.

Similar Taliban threats forced former military ruler Gen Pervez Musharraf, also known for his secular leanings, to cancel a welcome rally on 24 March, the day he returned to the country after a four-year long self-imposed exile.

Imran Khan's party drew a crowd of tens of thousands last month in Lahore

These threats follow huge election rallies already held by former cricketer Imran Khan's PTI, former prime minister Nawaz Sharif's PML-N and Maulana Fazlur Rahman's JUI-F.

Parties like Jamaat-e-Islami and the political wings of some of the jihadi and sectarian groups also have an open field for campaigning.

All these parties are either overtly religious, or are run by right-wing liberals with religious leanings.

Campaign of attacks

The question is, can the secularists defy the militant threat and assert themselves to ensure a level playing field in the vote?

An answer would depend on how serious the militant threat really is, and whether the country's intelligence-cum-security apparatus has the competence or the will to deal with it.

Islamist parties like the JUI face no threats in campaigning

Thus far, the militants have repeatedly demonstrated their ability to attack the secular parties, while the security forces have failed to clear them out of their known sanctuaries in the north-west.

The ANP party, which led the outgoing administration in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, has been the worst hit.

In October 2008, the party's chief, Asfandyar Wali, narrowly escaped a suicide bomb attack near his residence in Charsadda. Since then, the party's top leaders have limited their movements and have avoided public exposure.

A recent report by BBC Urdu said that more than 700 ANP activists have been killed by snipers or suicide bombers during the last four years, including a top party leader, Bashir Bilour.

In recent weeks, low-intensity bombs have gone off at several local ANP election meetings, reducing its ability to conduct an open campaign.

Wings clipped

The PPP's losses at the grassroots level are minimal, but it did suffer a major shock in 2007 when its charismatic leader and former prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, was assassinated in a gun and bomb attack.

The then government, which was headed by Gen Musharraf, blamed the attack on the Pakistani Taliban on the basis of some communication intercepts and half a dozen arrests.

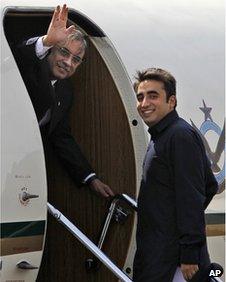

President Zardari (left) and his son Bilawal have yet to start campaigning

In June 2011, Ms Bhutto's husband and by then the president of Pakistan, Asif Zardari, was stopped from visiting his ailing father in an Islamabad hospital after the intelligence agencies uncovered what they claimed to be an assassination plot involving several Taliban suicide bombers.

As for the MQM, it has its main base in Karachi, and is reported to have a strong militant wing of its own, a claim it denies. But in recent months its activists have been targeted by the Taliban, including a provincial lawmaker, Manzar Imam.

Whether or not these parties will hit the campaign trail in a big way just as their right-wing competitors have done will become clear over the coming days and weeks.

They will be desperate to do so. Their leaders, especially those of the PPP and ANP, have been out of touch with the voters for nearly four years due to restricted movement.

Their inability to openly access the voters now may make it difficult for them not only to stem some of the unpopularity they may have earned during their incumbency, but also to prevent their more loyal vote-bank being eroded.

For many, the situation is becoming more like the 2002 elections, when the military regime of Gen Musharraf forced the main political leaders into exile, creating conditions for religious forces and conservatives to sweep the election.

Often those with the largest vote, the secular political forces have in the past had their wings clipped repeatedly by a powerful military establishment which finds an Islamic image of the state more suited to its security needs.

Now that job is being done by the Taliban.