What is behind Burma's wave of religious violence?

- Published

Jonathan Head: "20 boys from a Muslim school were cut down and burned on the spot"

Last month more than 40 people died in violence between Buddhists and Muslims in the central Burmese town of Meiktila. The BBC's South East Asia correspondent Jonathan Head looks at the causes of the violence.

At first sight it appears that Meiktila has been hit by a natural disaster. Entire neighbourhoods have been levelled, homes of brick and cement smashed to rubble.

Then you notice holes pounded into the walls that are still standing, clearly made by human hands. It was anger, not nature, that wreaked this destruction.

The families and shop-owners that occupied these buildings have disappeared. The only people are the scavengers, salvaging anything of value left in the ruins.

A Muslim community that dates back many generations has been wiped out.

After Muslim neighbourhoods were levelled, only scavengers could be seen at the site of the destruction

Just outside the town centre people stop to look at a blackened patch of ground. This is where at least 20 Muslim boys were taken, from a madrassa, and hacked to death, their bodies soaked in petrol and set alight. Fragments of charred bones still lie in the ashes, beside discarded shoes.

On the surface Meiktila seems calm and orderly. Soldiers, who are supposed to be less visible in the new Burma, are back on the streets. A night-time curfew is being enforced.

But the events in March have shaken Meiktila's member of parliament.

Win Htein is a man of proven courage, who spent 20 years in appalling conditions in prison because of his loyalty to Aung San Suu Kyi and the National League for Democracy. The former army captain has seen plenty of violence, but he still shakes his head in disbelief at what he witnessed last month.

"I saw eight boys killed in front of me. I tried to stop the crowd, I told them to go home. But they threatened me, and the police pulled me away.

"The police did not do anything - I don't know why. Perhaps because they lack experience, perhaps because they did not know what orders to give.

"On the bank thousands of people were cheering. When someone was killed, they cheered. And they were shouting 'they killed our monk yesterday, we must kill them'. There were women, monks, young people. I feel disgusted - and ashamed."

At least 12,000 Muslims are thought to have fled their homes because of the unrest

Around 30% of Meiktila's population is Muslim. They were prominent in its commercial life, owning many of the shops.

Now most of them have been herded into rudimentary camps, where they are tightly guarded by armed police.

Our attempts to enter and speak to the displaced people were politely rejected. We could see aid being delivered - international agencies are already visiting - but conditions seemed squalid, with almost no sanitation.

Monk's xenophobia

So what caused this frenzy of rage and hatred?

It started at a Muslim-owned gold-shop in the town centre on 20 March. People told me a Buddhist couple had gone to sell their jewellery. There was a dispute over the price, which escalated into a fight.

Then a Buddhist monk was attacked. He died later in the town hospital. News of that incident appears to have sparked off a sustained mob attack on all Muslim quarters.

An argument in this gold shop quickly escalated into widespread communal violence

There are differing views over how spontaneous the violence was, and whether outside, organised forces might have played a role.

But what is beyond dispute is the visceral fear and resentment of Muslims, openly expressed these days all over Burma. They refer to them with the derogatory term "kala".

The most prominent exponent of this view is a 45-year-old monk in Mandalay, Ashin Wirathu.

Imprisoned in 2003 for inciting anti-Muslim violence, he was released last year as part of the broader amnesty for prisoners.

He organised protests in support of Buddhists in Rakhine state, where communal violence broke out in June, and published speeches which have been widely distributed. He presents a frighteningly xenophobic picture of his country.

He agreed to meet me at his Ma Soe Yein monastery in Mandalay. Calm and softly-spoken, he projects a powerful charisma, and his many followers are clearly in awe of him.

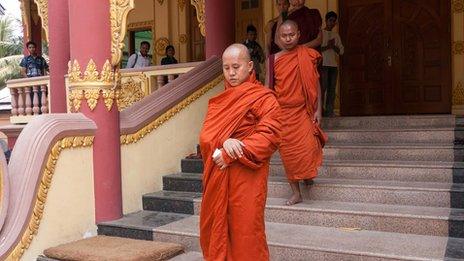

Ashin Wirathu (front) is urging Buddhists to boycott Muslim businesses

When I saw him he had just returned from Rangoon, where he had been summoned by the government to a meeting of religious leaders in order to ease community tensions.

So he has agreed to tone down his speeches, he told me.

But his hostility towards a Muslim minority making up at most 8% or 9% of the population seemed unchanged.

'969 stickers'

"We Buddhist Burmese are too soft," he told me. "We lack patriotic pride.

"They - the Muslims - are good at business, they control transport, construction. Now they are taking over our political parties. If this goes on, we will end up like Afghanistan or Indonesia."

Ashin Wirathu has amassed a collection of what he says is "evidence" of the evils of the Muslim community.

He accuses Muslim men of repeatedly raping Buddhist women, of using their wealth to lure Buddhist women into marriage, then imprisoning them in the home.

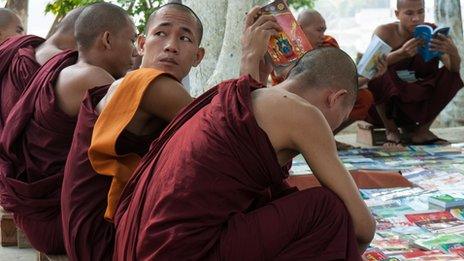

Burmese monks have a long tradition of political involvement

Their population is growing too fast, he says. They are taking over.

He shows me a book with a lurid cover, depicting a Buddhist woman cowering in terror before a giant, salivating wolf. Then he offers a chilling allegory.

"When you leave a seed, from a tree, to grow in a pagoda, it seems so small at first. But you know you must cut it out, before it grows and destroys the building."

He insists he played no role in the violence at Meiktila, although he was there. But he has not stopped campaigning.

He is urging Buddhists all over the country to boycott Muslim businesses.

So his followers have been distributing stickers printed with the number '969', which symbolise elements of Buddhism, to shopkeepers around Mandalay.

I went with Kyi Kyi Ma, a local estate agent, around the main market, and she pointed out with pride how many stalls had the sticker, identifying them as Buddhist.

Buddhist stalls are using stickers to identify themselves

A solitary Muslim stall-holder, in a headscarf, sat without customers.

Speaking in a nervous whisper, she told me her customers had fallen dramatically since the trouble in Meiktila.

"I am a businesswoman. I do not want to be involved in this," she said. "Maybe they don't like the way I dress."

Burma has a long history of communal mistrust, which was allowed to simmer, and was at times exploited, under military rule.

It is out in the open now, and spreading quickly in the new climate of freedom which was supposed to move the country towards a better, kinder future.

Many Buddhists are boycotting Muslim businesses