North Korea: Past lessons will affect the next move

- Published

Lessons from past confrontations will be key to Kim Jong-un's strategy

North Korea has a long history of confrontation with the outside world over its weapons' programmes. In the past it has claimed historic diplomatic victories over the United States and others. Is history about to repeat itself, or has North Korea miscalculated this time?

North Korea was an acknowledged master of Cold War diplomacy - playing China off against the Soviet Union to extract maximum assistance from its squabbling Communist backers.

Since the 1990s it has tried to master a different game - a survival strategy that uses threats and limited military action to divide its neighbours and enemies and extract concessions from them.

Even some US officials concede that Kim Jong-il played his hand with some skill.

The fear is that his son, Kim Jong-un, does not have the same touch or strategic grasp - and could provoke a conflict that no-one wants.

The new leadership, however, is using a familiar playbook - and has reminded the world that North Korea is at its most dangerous when confronted.

Pyongyang's strategic goal is a deliverable arsenal of nuclear weapons which it believes will guarantee the regime's survival in a hostile world. It wants to force the United States to acknowledge it as an equal and fellow nuclear power.

Washington's pursuit of sanctions - especially the targeting of the regime's finances - and its defiant military stance appear to have stung Kim Jong-un and his advisers into a spiral of escalation.

Past confrontations

The nuclear confrontation began two decades ago.

In 1994, it brought the small, crowded, heavily urbanised Korean peninsula close to a potentially cataclysmic war.

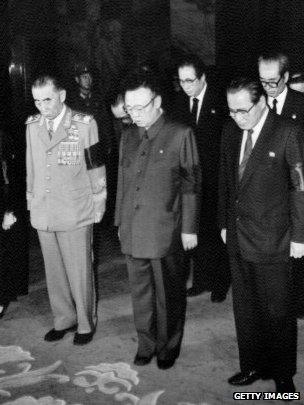

Kim Jong-il "humbled a superpower"

In the Spring of that year, the Clinton administration seriously considered air strikes on North Korea's small nuclear reactor at Yongbyon.

US military chiefs planned a massive reinforcement of American military forces in South Korea - a process that risked provoking the pre-emptive North Korean strike that it was designed to forestall.

After months of crisis, Washington finally agreed to direct talks with Pyongyang - a long term North Korean goal - and an agreement was reached that traded a nuclear freeze for economic aid diplomatic concessions.

It is debatable who blinked first. But two decades later, North Korea has a small and possibly growing stockpile of nuclear weapons - and the United States no longer contemplates going to war to stop it.

Kim Jong-il was celebrated in North Korea as a military genius who had humbled a superpower.

He also claimed a famous victory during another major confrontation with the US in 2002.

President George W Bush accused him publicly of cheating on the nuclear freeze - by developing a separate uranium enrichment programme - and spoke of North Korea as part of an "axis of Evil" at a time when talk of regime change was much in the air in Washington.

North Korea scrapped the nuclear deal and threatened retribution and war.

But once again, the crisis ended in talks - this time with North Korea's neighbours at the table as well - including Russia and its principal backer, China.

While the talks dragged on inconclusively, North Korea built up its nuclear arsenal and missile technology.

The North Korean leadership appears to have drawn an important lesson from these experiences.

It concluded that threats of chaos and war - in the midst of one of the world's must dynamic industrial regions - would always force adversaries to back down and grant concessions.

The bluff requires two ingredients: North Korea's threats must be credible. The leadership in Pyongyang must appear wild and irrational enough to risk a suicidal war.

And, North Korea's adversaries - in effect the United States - must have ruled out the threat of war as an ingredient in coercive diplomacy.

That effectively happened in 1994, when the Pentagon looked at a potential war on the Korean peninsula and concluded that it would lead to hundreds of thousands of casualties in a few days, and the destruction of one of the world's largest cities.

The new leadership

Kim Jong-un appears in a hurry to establish his credentials as a military leader - and poker player - in the mould of his father and grandfather.

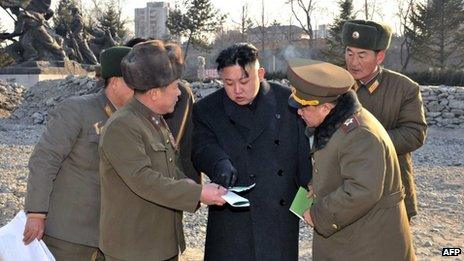

Unlike his father, Kim Jong-un has been keen to appear in public

He was unknown to the North Korean public just two years before he was appointed supreme ruler of the country and its million man army.

He now styles himself a great general, appearing in the front line and making very specific military threats - a dramatic contrast with his enigmatic father, who never made a public speech during his 17 years in power.

In the past, North Korea has relied on other regional players to lose their nerve and intervene with the United States, persuading it that war is too big a risk to take and that North Korea will respond well to incentives.

That may yet happen again. South Korea stands to lose the most from a conflict, Japan is within range of North Korean missiles and China wants to avoid chaos and the possible destruction of a buffer state on a key frontier.

But Kim Jong-un will first have to convince them that there is some substance to his threats.

His bellicose style and almost daily threats of war have gone well beyond the rhetoric employed by Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung.

Any military action would be sure to meet a determined response from South Korea and the United States.

China could yet intervene by cutting a crucial oil pipeline and other economic aid and trade if it concluded the new leader was out of control and bent on self destruction.

Kim Jong-un and his advisers are relying on an old script to bolster their position at home and abroad. It is far from clear that this time they will succeed.