Dhaka factory collapse: Can clothes industry change?

- Published

The latest tragedy to hit Bangladesh's ready-made garments industry has once again brought the power and influence of the industry into sharp focus.

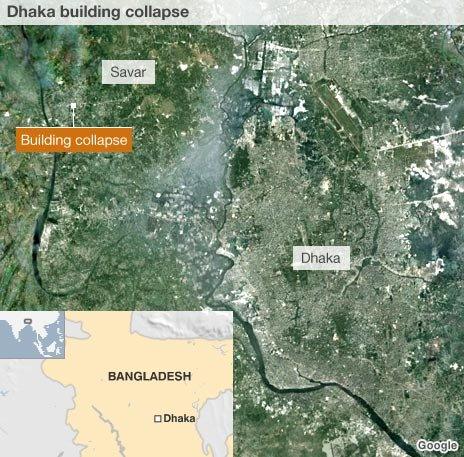

The collapse of Rana Plaza, an eight-storey building which housed five garment factories, is not the first incident of its kind.

Back in 2005, a similar building collapsed in the same town, leaving 64 garments workers dead. The factory owner was arrested but did not serve any time in prison.

Since then, there have been fires, stampedes and other incidents at various garment factories, causing hundreds of deaths.

Most recently, more than 100 workers perished in a fire at Tazreen Fashions in Ashulia, a township close to Dhaka where hundreds of factories are located.

In most of the incidents, the deaths were preventable. Often, workers could not escape because exits were locked.

"In my view, 50% of garment factories are located on premises which are not safe," said senior government official Mainuddin Khondker, who headed a task force to inspect garments factories following last November's fire at Tazreen Fashions.

But in the same interview with the BBC's Bengali service, Mr Khondker admitted no action had ever been taken against a factory for violation of safety rules, inadequate fire safety or, indeed, against landlords for violation of building codes.

Are clothes shoppers concerned about Bangladesh?

The garments industry appears to be wrapped in a culture of impunity.

Factory owners and senior officials of the industry body - the Bangladesh Garments Manufacturers and Exporters Association (BGMEA) - deny allegations that they get away with murder.

"This is a big sector, we have over 5,000 factories," said Siddiqur Rahman, a former senior vice-president of BGMEA.

"Accidents can happen, many fire incidents result from short circuits. But there should not be any deaths, they can be avoided through proper training," he told the BBC.

Key industry

There is a good reason why the ready-made garments sector is treated as the sacred cow of Bangladesh's economy.

From a humble beginning in the early 1980s, the industry has grown into a $20bn business that accounts for nearly 80% of the country's export earnings.

But more importantly perhaps for this poor, conservative Muslim nation, the industry has created jobs for four million workers, four-fifths of whom are women.

Millions of young girls from poor families have found jobs in this industry, helping them to break out of a life of dependency and grinding poverty.

But the country is paying a high price for this.

Syed Sultanuddin Ahmed, executive director at the Bangladesh Institute of Labour Studies (BILS), says the fast growth of the industry has outpaced other institutions.

Despite being built up by investors as well as workers with strong state support, Mr Ahmed says there is propaganda that the industry owes its success to the entrepreneurs alone.

"As this industry is creating jobs and earning foreign exchange, the state has created an impression that the garments industry must not be touched," Mr Ahmed told the BBC.

In order to capture the lower end of the global market, successive governments have promoted Bangladesh as the source of cheap clothing.

Cheap labour, fiscal support such as duty-free import of fabrics and accessories, and new infrastructure to help smoother, quicker exports have helped the industry grow rapidly.

But the lure of quick dollars has attracted a whole range of cowboy operators who cut corners to drive costs further down.

The result is factories in unsafe buildings with poor safety measures.

The BGMEA vigorously defend its corner, denying members exploit workers or receive special protection from the government.

"Garments factories are no longer like they used to be," said BGMEA Vice-President Shahidullah Azim. "There are some poor ones and they will be closed down."

A former BGMEA president, Abdus Salam Murshedi, said the lowest wages offered to new starters by garment factories were better than most workplaces in Bangladesh.

"At least in the garments industry we are paying newcomers to work and learn. In other sectors, they have to pay their employers to work as apprentices," he said.

Big international brands continue to do business with the BGMEA because they are in the market for the cheap clothes Bangladesh can supply.

Election hope

While the government treats the garments industry as a strategic asset to be protected at all costs, the BGMEA has worked to increase its own political muscle.

A number of factory owners have gone into politics, gaining seats in parliament, becoming ministers, with many BGMEA members joining the two major political parties.

Garments entrepreneurs are reputed to be some of the most generous financiers of political parties.

Optimists in Bangladesh feel the Rana Plaza tragedy could be the straw that will break the camel's back.

The high death toll and the criminal negligence that caused it may just be too much even for the Bangladesh government to ignore, especially in an election year.

In a few months, the governing Awami League and opposition Bangladesh Nationalist Party will be slugging it out in the polls.

The big question is: Will the political parties respond to public outrage and finally bring negligent factory and building owners to book?

Or, after the dust has settled on yet another human tragedy at a garment factory, will it be business as usual?

- Published25 April 2013

- Published17 January 2013

- Published25 April 2013

- Published25 April 2013