Stakes high in Malaysia's pivotal election

- Published

About a quarter of Malaysia's electorate are first-time voters

On Sunday 5 May Malaysians will vote in the most hotly contested general election in their country's history.

For the first time since independence in 1957, there is a real possibility that the Barisan Nasional (National Front) coalition of Prime Minister Najib Razak may be defeated by the Pakatan Rakyat alliance nominally headed by Anwar Ibrahim.

As in any election a host of local and national issues are being debated in the campaign, with accusations and counter-accusations flying back and forth at rallies, in newspapers, TV channels and websites, but at its heart is a simple choice for Malaysia's 13 million voters.

Do they stick with a coalition which, for all the accusations of corruption and cronyism, has delivered solid economic growth and political stability? Or do they chance handing power to a vigorous but largely untested opposition?

Opinion polls suggest the result is too close to call. There is a great deal at stake for both leaders.

The Barisan Nasional coalition reminds voters that they have benefited from its economic policies

For Najib Razak, the son of a prime minister, losing his first election as prime minister (he got the job in 2009 when his predecessor resigned), and presiding over his party's first ever defeat, would be a crushing blow, and perhaps the end of his long political career.

He would almost certainly be challenged for the party leadership.

For Anwar Ibrahim, now 65 years old, this may be his last chance to complete a remarkable comeback, 15 years after he was sacked as deputy prime minister, jailed, beaten and repeatedly prosecuted on what he has always believed were politically-motivated charges.

Failure to win this time could break up the coalition he has built, from his own reformist Keadilan party, the Islamic party PAS, and the ethnic Chinese party DAP.

Cheap rice and petrol

Both men have been campaigning relentlessly across the country, aware that every vote is important. Watching them both on the same day, the differences in style were revealing.

Crowds braved the pouring rain to take part in an opposition rally

Mr Anwar arrived in pouring rain at a rally in a patch of ground next to a highway in a Kuala Lumpur suburb.

Despite the weather and the late hour, an enthusiastic crowd spilled out into the street, to watch him pour scorn on the government's performance and promises with characteristic energy.

It had the feel of a grassroots campaign, with palpable excitement about the possibility of change.

Mr Najib chose a desolate housing estate on the outskirts of Kuala Lumpur, still surrounded by bits of tropical forest.

There were plenty of Barisan volunteers on hand, brandishing 'WE LOVE PM' banners, but the rest were families who had been waiting to move into the apartment blocks for 12 years. The privately-built project had stalled; now with government funds it had been finished.

The prime minister's arrival was accompanied by plenty of fanfare, patriotic songs, and lots of food laid out under tents.

Mr Najib appeared tired, and his speech lacked the passion of opposition rallies.

But its message was clear, and consistent with Barisan's campaign theme. We have finished this project for you, he said, before handing out keys to the residents. The state government, he said - which has been in the hands of Pakatan since the last election - did not.

Time and again, Barisan TV ads have reminded Malaysians of what the governing coalition has done for them. Cheap rice, cheap petrol, and reliable drinking water, all thanks to generous subsidies.

This has been backed by a whole raft of government hand-outs over the past year, ranging from bonuses for civil servants to vouchers for schoolbooks.

Separating normal welfare spending from pre-election freebies is difficult, but one academic, Bridget Welsh from the Singapore Management University, estimates Barisan has spent an extra $1,500 (£960) per voter.

'Undercurrent of dissatisfaction'

The other argument Barisan is using to sway the voters is fear of what might happen if Pakatan wins, playing on its inexperience, and on the disparate ideologies of its three parties.

In particular, it has zeroed in on the commitment of PAS to introduce huddud, or Islamic punishment, in the hope of scaring off non-Muslim voters.

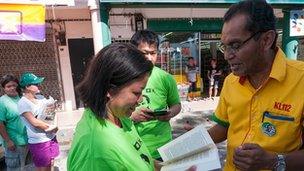

Chinese voters said Islamic MP Dzulkefly Ahmad's honest reputation appealed

But that argument appears to be struggling.

Polls suggest increasing numbers of ethnic Chinese are swinging towards Pakatan, put off the government by both its entrenched corruption and the way ethnic Malays are still favoured in access to education and to lucrative government contracts under the New Economic Policy introduced back in the 1970s.

"Only a small cluster, an inner circle of Malays, benefit from the New Economic Policy", says Stanley Thai, chairman of Supermax, a company that makes and exports latex products.

He is now openly supporting the opposition, arguing that change is vital for Malaysia.

"It's like in any business. If you don't face competition, you think you're the best - but actually you're not."

"This is our opportunity for the country to say OK, a two-party system is the best way to go. I would rather take a risk to have Pakatan Rakyat form the next government, than the current government of Barisan Nasional."

What do first-time voters think about the election?

Ghazali Yusoff, an ethnic Malay businessmen who founded Nusatek, a company that tests components for infrastructure and the oil industry, says he is still sticking with Barisan, despite reservations about its performance.

"This is not the time to change", he said. "Prime Minister Najib has done well, his policy of economic transformation is beginning to work."

"He deserves another chance. If he still cannot bring about reforms, then I would be willing to support the opposition."

The Islamic wing of the opposition is working hard to soften its theocratic image, to reach across Malaysia's ethnic and religious divide.

In Kuala Selangor, a semi-rural constituency narrowly won by PAS at the last election, I watched MP Dzulkefly Ahmad doing the rounds of food stalls and grocery shops, accompanied by his headscarfed wife.

He was greeted warmly by the mainly ethnic Chinese shop-owners, who happily donned his green campaign T-shirts and asked for signed copies of his book. They were unfazed by talk of Islamic law.

What mattered, they told me, was Dr Dzulkefly's reputation for honesty and hard work.

"I am an Islamist democrat," he told me.

Marimuthu Seeniueasan holds keys to his new apartment - a project finished by the government

"Islamic punishment will only be introduced if it is democratically approved by the Malaysian population. We may fail - but at least allow us to advocate what we believe."

Perhaps the most uncertain factor in this election is how first-time voters, around one quarter of the electorate, will cast their ballots.

Polls suggest they are more sympathetic to the opposition, and they are more exposed to alternative views on social media and websites. The mainstream media is for the most part blatantly pro-government.

"Malaysians have become more affluent, and have developed new tastes", says Ibrahim Suffian, from the Merdeka Center for Opinion Research.

"There is an undercurrent, a sense of dissatisfaction that a lot of the promises made in the past, about cleaning up government, fighting corruption - that these have not happened".

- Published1 May 2013

- Published1 May 2013

- Published1 May 2013

- Published28 July 2020

- Published24 November 2022

- Published2 May 2013