Can Nawaz Sharif walk the military tightrope?

- Published

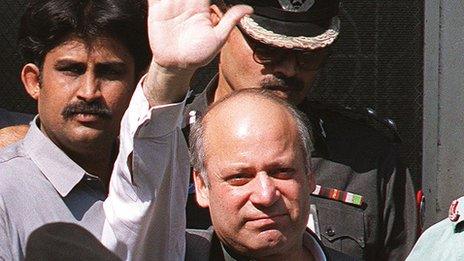

Last time he was PM, Nawaz Sharif was toppled in a military coup

Nawaz Sharif knows better than anyone how powerful Pakistan's military are. He was toppled by them in 1999. So who is really going to be running the country now that he will be prime minister?

In Pakistan's politically savvy drawing-rooms conversations inevitably come round to the question of whether Mr Sharif has learned any lessons from the past.

Back in the late 1990s, when he commanded a two-thirds majority in parliament, he sacked one army chief, and nearly sacked another. The second one launched a dramatic counter-coup and Mr Sharif ended up exiled in Saudi Arabia.

Months earlier, just when he had been trying to mend fences with arch-rival India, the generals rained on his parade by launching the Kargil conflict in Indian-administered Kashmir. He says they did it behind his back.

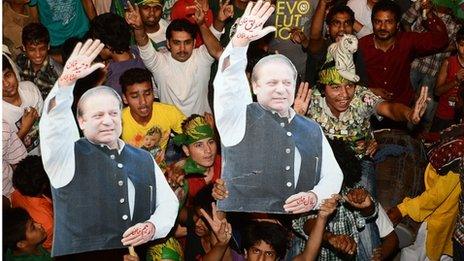

Mr Sharif is back in power now, with a mandate that is only slightly smaller than the one he was given in the 1990s, but the challenges he faces are much more complicated than just rapprochement with India.

Choppy waters ahead

So how is he likely to fare vis-à-vis the military?

The current army chief, Gen Ashfaq Kayani, is set to retire in the coming months

Ayesha Siddiqua Agha, an expert on military affairs, says he will at least have a smooth honeymoon period.

"Army chief General Kayani is to retire six months later, and the new chief will need a couple of months more to ease into his new job," she says.

There is a chance, however, that Mr Sharif will hit choppy waters earlier than that.

His greatest challenge lies in reviving an economy that is on the brink of collapse.

But nearly all the options to help a quick revival require fine-tuning of the country's geo-strategic environment, which is shaped and controlled by the military.

The foremost pre-requisites for economic growth - peace and security - have become hostage to an increasingly aggressive Pakistani Taliban (TTP).

The group is part of a wider militant network that has been destabilising Afghanistan from sanctuaries in Pakistan's Federally Administered Tribal Areas (Fata), and which is considered by many to be a "strategic asset" of the Pakistani military.

Mr Sharif has indicated he wants to hold talks with the TTP because, as he puts it, fighting them in the past has not helped curb the menace.

A former security chief of Fata, Brig Mehmood Shah, says negotiations have also not worked in the past. He is confident Mr Sharif will discover that soon enough.

"The military wants to eliminate militant sanctuaries and has the capacity to do so. All it wants is that its efforts be backed by a wider political consensus and ownership," he says.

If this is true, does it signify a paradigm shift?

Ambivalence towards militancy?

Defence analyst Dr Hasan Askari Rizvi is sceptical.

"The thinking in the military is as confused as that of Mr Sharif," he says.

Mr Sharif has had troubled relations with Pakistan's military

"They want political sanction to move against the TTP, but they don't want to upset all the militant groups because they still think they may need them in Afghanistan after Nato troops leave in 2014."

This means that "the military's policy of ambivalence towards militancy will continue", he says.

Mr Sharif's relations with the military will also be tested when it comes to promoting trade and investment with India, another option which economic experts believe can rejuvenate Pakistan's economy in the short term.

India has long been viewed by the military as the enemy with which it fought three regular wars, one covert war in Kargil, and a 15-year proxy guerrilla war in Kashmir.

In the past, efforts by politicians to normalise relations with India have been resisted by the military, including those by the outgoing PPP-led government which has just completed its term in office.

But many feel that may no longer be the case.

"I believe the military's thinking on India has changed," says Lt Gen Talat Masood, now retired and working as a security analyst.

"They know that their main bone of contention with India - the dispute over Kashmir - is not likely to be resolved any time soon. Therefore, a continued stand-off with India only hurts us economically and also leads to a loss of our leverage with both India and the West."

Western powers, especially the United States which provides the bulk of international assistance to Pakistan, have been keen to see a normalisation of relations between the two nuclear-armed neighbours.

Mr Sharif 's PML-N party won the elections with an emphatic majority

But if Pakistan continues to be seen to be supporting insurgents in Afghanistan, India will still feel threatened and keep pushing for action against elements involved in the 2008 Mumbai attacks.

A concession to the Indians on this score may not go down well with the military and its surrogate groups, analysts believe.

Foreign policy control

So Mr Sharif will be walking a tightrope - but given his history, many feel he may still make an attempt to snatch the initiative from the military.

If he does that, it will be partly because of the general belief that the military has lost the appetite, or the ability, to stage a coup given the country's diplomatic isolation and its economic troubles.

Some analysts suggest he has already been doing some spadework to that effect.

The tables have turned for Pervez Musharraf

In a recent statement Mr Sharif indicated that he would hold an inquiry into the Kargil invasion, which he has so far blamed on former army chief, Pervez Musharraf, and some other generals of the time.

Mr Musharraf was also the general who toppled his government in 1999. The tables are now turned and he is currently under house arrest in Pakistan where he is being tried for failing to ensure the security of another former prime minister, Benazir Bhutto, who was assassinated in 2007.

The arraignment of these generals on a high treason charge in the Kargil affair or for other actions they took during the nine years of Musharraf rule would set a dangerous precedent for the military.

Ayesha Siddiqua believes Mr Sharif is using that threat to push for greater control of foreign policy which until now has been the exclusive domain of the military establishment.