Will new Nauru asylum centre deliver Pacific Solution?

- Published

The BBC's Nick Bryant gained access to a detention centre on the island of Nauru

On the remote tropical island of Nauru, a country so small that it looks like a fleck on the map, Australia is once again trying to solve its boat-people problem.

It was here, in 2001, that the policy of processing asylum seekers in offshore camps rather than on the Australian mainland, known as the Pacific Solution, external, got under way when the conservative government of then-Prime Minister John Howard opened its first detention centre.

To its backers, the Pacific Solution was seen as a potent deterrent that succeeded in stopping the boats.

However, human rights groups viewed it as emblematic of Australia's heartlessness towards asylum seekers trying to reach its shores, criticising the conditions in which people were held, as detainees went on repeated hunger strikes.

The controversial policy was scrapped by the Labor government in 2008, but following a rise in asylum seekers arriving by boat, Labor has brought it back.

A new detention centre opened in Nauru in September 2012, but it too has been beset by criticism.

Until earlier this year asylum seekers were housed in overcrowded army tents

When Amnesty International visited in November 2012, it delivered a withering assessment, calling the detention centre "a toxic mix of uncertainty, unlawful detention and inhumane conditions that are creating an increasingly volatile situation, external."

Now the BBC has been shown secretly-filmed footage, obtained by Australian broadcaster ABC, taken inside the detention centre where until earlier this year people were enduring stifling humidity and temperatures reaching 45C in overcrowded army tents.

We have been shown smuggled-out photographs which show asylum seekers who have sewn their lips together in silent protest at their indefinite detention and other acts of self-harm.

Suicide attempts

And we have heard harrowing testimony from Australians working inside the camp, who have described the suicide attempts detainees have made, and spoken of their shock at the conditions.

"Men are cutting themselves, burning themselves with cigarettes," one worker said. "We've had men attempt to commit suicide using bed sheets, using the ropes off tents. We've had men attempt to jump off scaffolding of construction sites, and we've had men trying to jump off cliffs at the back of the camp."

"I feel like it's a last act, a desperate act. For them they see no future and they see no hope of leaving. They've been in Nauru for nine months and they have no idea if it will be another nine months, or another three years, or another five years," they added.

The asylum seekers are subject to the Australian government's new no-advantage principle, external which could see them being detained for up to five years.

Despite its tropical setting and swaying palms, Nauru is far from paradise. Dotted with razor-sharp coral, its seas are uninviting. If the jagged coastline reinforces the sense of enclosure, the four-and-a-half-hour flight from Brisbane intensifies the sense of isolation.

Secret filming obtained by ABC shows asylum seekers who have sewn their lips together in protest

The road encircling the island, which takes little more than 20 minutes to drive in full, is lined with dilapidated dwellings and half-derelict buildings. The resources companies lured here by the high-grade phosphate, a sought-after fertiliser ingredient, have ravaged the island's interior.

In the 1970s and 1980s, the heyday of Nauru's mining boom, this small republic with a population of just 10,000 people was, per capita, one of the richest nations in the world.

Now it is one of the poorest, and that is a central reason why successive Nauru governments have agreed to play host to Australia's off-shore processing of asylum seekers. It helps guarantee a line of Australian aid, and boosts local employment.

Identities hidden

Thick jungle surrounds the detention centre, both separating and camouflaging it from the outside world. Until now the Australian government has imposed a strict media ban here, but the BBC is first news organisation to be allowed inside.

Australia's Department of Immigration and Citizenship clearly wanted us to see how Nauru's tent city has been replaced by permanent accommodation, in a project that has cost almost A$100m ($95m, £61m).

It is currently home to more than 400 men from Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan, Iraq, the Palestinian Territories and one from Azerbaijan.

In the past more than 90% of boat people have eventually been found to be bona fide refugees, but when filming we are not allowed to show detainees' faces or reveal their names in case their asylum claims are rejected and they are sent home.

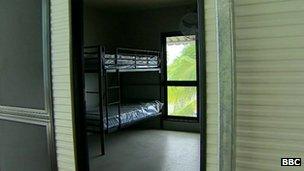

The new rooms, each of which houses two "clients", as the asylum seekers are called by the authorities, contain a bunk-bed, desk, lockers and two personal safes.

There is still no air conditioning, but every room has a large fan and natural ventilation. On the landing outside each room, there is a communal area so the asylum seekers can mingle.

A lot of them spend the day in a central courtyard, part of which is protected from the harsh sunlight by a canopy. There are cultural flourishes. The old tents, for instance, have become places of worship.

The food provided offers a taste of home. There are plasma screens broadcasting television channels from their countries of origin and a recreation centre with games consoles and exercise equipment.

Calls home

Banks of computers grant access to e-mail and the internet, and asylum seekers are given phone cards so they can make calls home. They earn extra phone card credits if they sign up to English language classes and other educational activities.

Nauru's tents have been replaced by permanent structures at a cost of A$99.3m

Though there is a heavy security presence, the approach stops short of being penal. There is no fence or razor wire, but the jungle creates a natural barrier.

The detainees are allowed to leave the camp on supervised excursions to swim in the ocean, play volleyball or to go on walks.

Apparently, one of the concerns that the Australian Department of Immigration had before granting us entry was that the new facilities may look too attractive, especially since the BBC's global reach means that our pictures will be seen internationally. This detention centre, after all, is supposed to be a deterrent.

Compared to the tent city, there is no question that the physical conditions here are vastly improved.

But we were not allowed to speak to the men themselves, so it was hard for us to assess their psychological condition, and how they were dealing with the torment of being kept on such a remote island, separated from loved ones - potentially for years.

U-turn

For the Labor government, the return to the Pacific Solution is an embarrassing reversal. In announcing the end of the policy when it took office in 2007, the-then immigration minister Chris Evans described it "as a cynical, costly and ultimately unsuccessful exercise."

Critics say the same is true of the revived policy.

The BBC is the first broadcaster to be allowed in to see the new facilities

The Labor government was asked to comment on Newsnight's report from Nauru, but they declined.

The return to off-shore processing is also costing a huge amount of money to implement. The operating expenditure in Nauru to 30 April was A$112.9m, and capital expenditure over the same period was A$99.3m.

And this tougher policy has failed to stop the boats. Since the government announced its return to the Pacific Solution, 21,730 passengers have arrived in Australian waters in 340 boats.

Watch Nick Bryant's film in full on Newsnight on Thursday 20 June 2013 at 2230 BST on BBC Two and then afterwards on the BBC iPlayer and Newsnight website.

- Published27 October 2023

- Published23 November 2012

- Published10 October 2012

- Published14 September 2012

- Published23 August 2012