Ghulam Azam: War crimes trial that exposed Bangladesh scars

- Published

The war crimes trials have bitterly divided Bangladeshi society

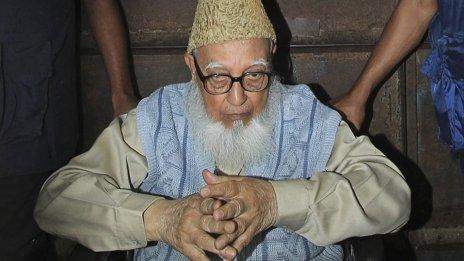

The conviction of Ghulam Azam on charges of crimes against humanity during the 1971 war of independence may help to close a bloody chapter in Bangladesh history - but it exposes a deep divide in this largely Muslim nation of 160 million people.

One of Bangladesh's most controversial political figures, Azam's trial by the International Crimes Tribunal in Dhaka has been possibly the most eagerly awaited legal event in the country's history. It has also been the most anxiously-watched political event.

The crimes, for which Azam and his colleagues in the Jamaat-e-Islami party are being tried, were committed 42 years ago. Bangladesh says up to three million people were killed in what the judges at Azam's trial called the worst genocide since WWII.

"It is undeniable that a massive genocide took place in the then East Pakistan," Justice Anwarul Haque said in his verdict.

"This massacre can only be compared to the slaughter by Nazis under the leadership of Adolf Hitler."

Long campaign

Pakistan was created in 1947 out of the British Empire in India, to act as a "home" for Muslims of the sub-continent. Its two wings - West and East Pakistan - had little in common except a shared religion. The two wings were separated by thousands of miles of Indian territory and differences in language, culture and history.

The rise of Bengali nationalism, based on language and a culture that predates Islam in the region, made Pakistan's existence as a unified state untenable. An attempt by the military rulers in Islamabad to crush the nationalists triggered the war which ended when neighbouring India entered the fray in December 1971.

The birth of Bangladesh was supposed to have put paid to the so-called "Two Nation" theory in the subcontinent, which suggested Muslims and Hindus could not live in one country and needed separate states. Bangladesh was supposed to be a haven of sectarian harmony and secular democracy.

Mr Azam's Jamaat-e-Islami party has called a general strike over the verdict

Things changed from the middle of the 1970s when a series of coups and uprisings left the leaders of the independence movement dead - including the country's founding father Sheikh Mujibur Rahman - and the military firmly in power.

The first military strongman, Gen Ziaur Rahman, and later Gen Hussain Muhammad Ershad, changed the constitution to remove references to secularism as a state principle and enshrined Islam as a "state religion".

Both generals encouraged the Islamisation of Bangladesh society. Religion was also allowed in politics.

A number of religion-based political parties such as the Jamaat were banned in 1972 for their roles in collaborating with the Pakistan army. Jamaat's top leaders had gone into hiding to escape the trials of alleged collaborators which began within months of independence.

But the military governments lifted the ban on religion-based politics and the Jamaat-e-Islam soon reappeared on the political scene. Ghulam Azam, who had fled to Pakistan before the end of the war, returned in 1978.

The return of Azam jolted the secularists into action, and a long campaign began to demand he and his Jamaat colleagues be tried for crimes committed in 1971.

Successive governments avoided the issue of trials, as they feared this would re-open the wounds of 1971. They also feared that a backlash from Jamaat would be difficult to contain and might destabilise the state.

Islam under attack?

Sheikh Hasina's Awami League made the trials part of their manifesto in the parliamentary elections of December 2008. Holding the trials promised both emotional and political dividends.

Firstly, it would justify the Awami League's claim to be the "party of liberation", having led Bangladesh to independence in 1971. Secondly, it would drive a wedge through the opposition coalition, where Jamaat is the junior partner with the much-larger Bangladesh Nationalist Party or BNP.

The setting up of the war crimes tribunal three years ago was fraught with risks. The immediate risk came from possible violence, which a well-organised party with a youth cadre of fanatical followers could unleash. But a bigger threat to the country's longer term stability came from reopening old wounds.

With their backs to the wall, Jamaat and its allies sounded an old alarm bell again, claiming Islam itself was under attack. The trials were branded as attacks on Islam and Muslims. Ironically, they were helped in this regard by huge demonstrations at a place in Dhaka called Shahbag, demanding the death penalty for Jamaat leader Abdul Qader Mollah after he was given life imprisonment.

Secular future uncertain

Young bloggers and online activists who organised the Shahbag demonstrations were accused of insulting Islam and its Prophet Muhammad. One such blogger, Rajib Haider, was murdered by a group of young Islamists. A newly-formed coalition of Islamist groups called Hefazate Islam accused the Shahbag gathering itself of promoting "un-Islamic behaviour and views".

This helped create an "Islamic wave" across the country which sought to generate sympathy for the elderly leaders of Jamaat facing the hangman's noose.

The BNP, sensing emotional and political dividends in equal measure, has thrown its lot in behind the Islamists, even while treading carefully on the issue of war crimes trials. Although a largely secular party itself, the BNP has not shied away from using Islamist rhetoric to attack the government.

The argument that was apparently settled in 1971, that Bangladeshi identity was based on its Bengali language and culture, is under challenge once again. The Awami League's attempt to revive a secular Bangladesh appears to be faltering under the challenge, although it appears determined to press ahead with the trials.

The next parliamentary elections are just six months away - they have to be held by 15 January, 2014. The outcome of these elections, and what follows them, will help determine whether Bangladesh can retain its secular outlook.

- Published15 July 2013

- Published21 January 2013

- Published4 September 2016

- Published9 May 2013

- Published3 March 2013