Was My Lai just one of many massacres in Vietnam War?

- Published

US Army helicopters pour machine-gun fire into the tree line to cover the advance of ground troops

In 1968 US soldiers murdered several hundred Vietnamese civilians in the single most infamous incident of the Vietnam War. The My Lai massacre is often held to have been an aberration but investigative journalist Nick Turse has uncovered evidence that war crimes were committed by the US military on a far bigger scale.

In a war in which lip service was often paid to winning "hearts and minds", the US military had an almost singular focus on one defining measure of success in Vietnam: the body count - the number of enemy killed in action.

Vietnamese forces, outgunned by their adversaries, relied heavily on mines and other booby traps as well as sniper fire and ambushes. Their methods were to strike and immediately withdraw.

Unable to deal with an enemy that dictated the time and place of combat, US forces took to destroying whatever they could manage. If the Americans could kill more enemies - known as Viet Cong or VC - than the Vietnamese could replace, the thinking went, they would naturally give up the fight.

To motivate troops to aim for a high body count, competitions were held between units to see who could kill the most. Rewards for the highest tally, displayed on "kill boards" included days off or an extra case of beer. Their commanders meanwhile stood to win rapid promotion.

Very quickly the phrase - "If it's dead and Vietnamese, it's VC" - became a defining dictum of the war and civilian corpses were regularly tallied as slain enemies or Viet Cong.

Civilians, including women and children, were killed for running from soldiers or helicopter gunships that had fired warning shots, or being in a village suspected of sheltering Viet Cong.

At the time, much of this activity went unreported - but not unnoticed.

Civilian casualties

Researching post-traumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans, in 2001 I stumbled across a collection of war crimes investigations carried out by the military at the US National Archives.

Box after box of criminal investigation reports and day-to-day paperwork had been long buried away and almost totally forgotten. Some detailed the most nightmarish descriptions. Others hinted at terrible events that had not been followed up.

At that time the US military had at its disposal more killing power, destructive force, and advanced technology than any military in the history of the world.

The amount of ammunition fired per soldier was 26 times greater in Vietnam than during World War II. By the end of the conflict, America had unleashed the equivalent of 640 Hiroshima-sized atomic bombs on Vietnam.

Vast areas dotted with villages were blasted with artillery, bombed from the air and strafed by helicopter gunships before ground troops went in on search-and-destroy missions.

The phrase "kill anything that moves" became an order on the lips of some American commanders whose troops carried out massacres across their area of operations.

While the US suffered more than 58,000 dead in the war, an estimated two million Vietnamese civilians were killed, another 5.3 million injured and about 11 million, by US government figures, became refugees in their own country.

Today, if people remember anything about American atrocities in Vietnam, they recall the March 1968 My Lai massacre in which more than 500 civilians were killed over the course of four hours, during which US troops even took time out to eat lunch.

Far bloodier operations, like one codenamed Speedy Express, should be remembered as well, but thanks to cover-ups at the highest levels of the US military, few are.

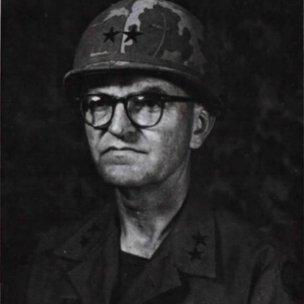

Gen Julian Ewell earned the nickname Butcher of the Delta during his time in Vietnam

Industrial-scale slaughter

In late 1968, the 9th Infantry Division, under the command of Gen Julian Ewell, kicked off a large-scale operation in the Mekong Delta, the densely populated deep south of Vietnam.

In an already body count-obsessed environment, Ewell, who became known as the Butcher of the Delta, was especially notorious. He sacked subordinates who killed insufficient numbers and unleashed heavy firepower on a countryside packed with civilians.

A whistle-blower in the division wrote to the US Army Chief of Staff William Westmoreland, pleading for an investigation. Artillery called in on villages, he reported, had killed women and children. Helicopter gunships had frightened farmers into running and then cut them down. Troops on the ground had done the same thing.

The result was industrial-scale slaughter, the equivalent, he said, to a "My Lai each month".

Just look at the ratio of Viet Cong reportedly killed to weapons captured, he told Westmoreland.

Indeed, by the end of the operation Ewell's division claimed an enemy body count of close to 11,000, but turned in fewer than 750 captured weapons.

Westmoreland ignored the whistle-blower, scuttled a nascent inquiry, and buried the files, but not before an internal Pentagon report endorsed some of the whistle-blower's most damning allegations.

The secret investigation into Speedy Express remained classified for decades before I found it in buried in the National Archives.

The military estimated that as many as 7,000 civilians were killed during the operation. More damning still, the analysis admitted that the "US command, in its extensive experience with large-scale combat operations in South East Asia, appreciated the inevitability of significant civilian casualties in the conduct of large operations in densely populated areas such as the Delta."

Indeed, what the military admitted in this long secret report confirmed exactly what I also discovered in hundreds of talks and formal interviews with American veterans, in tens of thousands of pages of formerly classified military documents, and, most of all, in the heavily populated areas of Vietnam where Americans expended massive firepower.

Survivors of a massacre by US Marines in Quang Tri Province told me what it was like to huddle together in an underground bomb shelter as shots rang out and grenades exploded above.

Fearing that one of those grenades would soon roll into their bunker, a mother grabbed her young children, took a chance and bolted.

"Racing from our bunker, we saw the shelter opposite ours being shot up," Nguyen Van Phuoc, one of those youngsters, told me. One of the Americans then wheeled around and fired at his mother, killing her.

Many more were killed on that October day in 1967. Two of the soldiers involved were later court martialled but cleared of murder.

Commemoration

Last year, the Pentagon kicked off a 13-year programme to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the war. An entry on the official Vietnam War Commemoration website for My Lai describes it as an "incident" and the number killed is listed as "200" not 500.

Speedy Express is referred to as "an operation that would eventually yield an enemy body count of 11,000".

There is almost no mention of Vietnamese civilians.

In a presidential proclamation on the website, Barack Obama distils the conflict down to troops slogging "through jungles and rice paddies… fighting heroically to protect the ideals we hold dear as Americans… through more than a decade of combat".

Despite what the president might believe, combat was just a fraction of that war.

The real war in Vietnam was typified by millions of men, women, and children driven into slums and refugee camps; by homes, hamlets, and whole villages burnt to the ground; by millions killed or wounded when war showed up on their doorstep.

President Obama called the Vietnam War "a chapter in our nation's history that must never be forgotten". But thanks to cover-ups like that of Speedy Express, few know the truth to begin with.

About the author: Nick Turse has been researching US military atrocities in the Vietnam War for more than a decade and has detailed his findings in a book Kill Anything That Moves: The Real American War in Vietnam.

A Pentagon spokesman, when asked for a statement about the evidence presented, said he doubted that more than 50 years after the US went to war in Vietnam, it would be possible for the military to provide an official statement in "a timely manner."