Q&A: Cambodia strives for "credible" election

- Published

The CPP says it has bought stability and economic progress

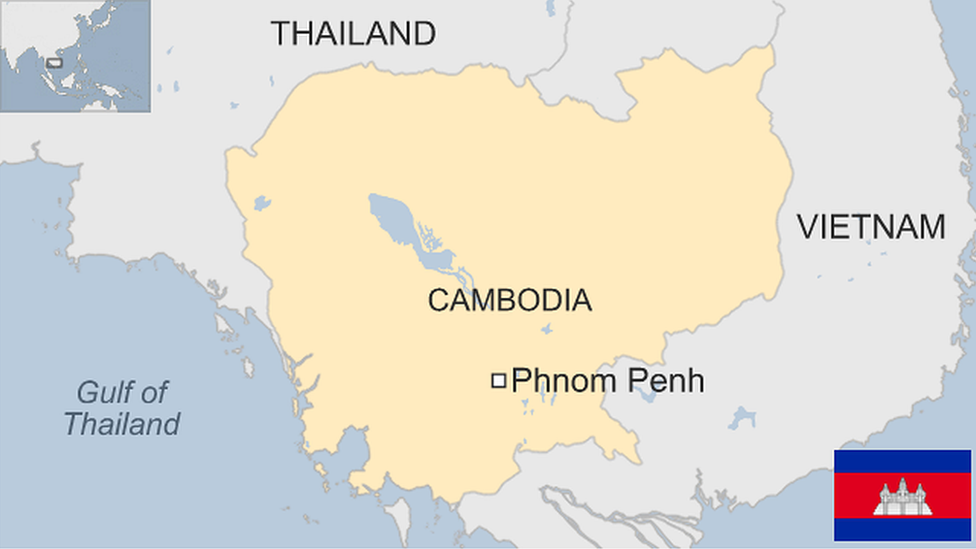

On 28 July, Cambodians will vote in a general election for the fifth time since their country became a multi-party democracy in 1993.

A win for the ruling Cambodian People's Party (CPP) seems a sure thing for Prime Minister Hun Sen, Asia's longest-serving prime minister.

But a last-minute return from exile by his long-time charismatic rival, Sam Rainsy, created excitement in the main opposition camp.

When it emerged Mr Rainsy could not stand as a candidate in the week before the polls, doubt was once again cast on the fairness of the election. Some observers wonder if the election result will be accepted by the public.

Why does the vote matter?

Cambodia is one of the region's poorest countries, and the perception that the election is being conducted fairly could affect its economy.

For 28 years, Hun Sen has tightened his grip on power, raising questions about Cambodia's democratic credentials.

Some US senators have called for a freeze on US aid to Cambodia if this election is not credible and competitive.

Soon after the US criticism, a ban on foreign media broadcasts was lifted and opposition leader Sam Rainsy received a royal pardon, allowing him to return to Cambodia from Paris, where he had been living since 2009 to avoid a jail sentence.

Independent media reported large crowds welcoming Mr Rainsy, who is a familiar face on the Cambodian political scene.

Who are the main players?

Hun Sen, 61, has been prime minister since 1985 as part of various coalitions.

Critics say the CPP enjoys the advantages of decades-long incumbency: a pliant court system and government administration, a near-monopoly on the media, and support from the army, police and a clique of tycoons.

Opposition leader Sam Rainsy, 64, leads the Cambodia National Rescue Party (CNRP), which is considered to be the only party out of eight competing in the election able to pose a serious challenge to the incumbent.

Since Mr Rainsy was blocked from participating on 22 July, it is unclear whether the CNRP's deputy president, Kem Sokha, will stand as a candidate. Mr Sokha founded the Human Rights Party that merged with Mr Rainsy's party to form the CNRP last year.

Sam Rainsy (centre) was welcomed by supporters on his return to Cambodia

What are the campaign issues?

The CPP is campaigning on a simple message of stability and economic progress.

The majority of Cambodians live in poor rural areas and the party says it has presided over a period of peace and economic growth.

It has steadily increased its share of National Assembly seats since 1993, now holding 90 of the 123 seats and controlling appointments to the National Election Committee.

But the opposition CNRP wants to focus on corruption, and particularly on a steep rise in state-backed land confiscation which has caused discontent since the last election in 2008.

Who are the voters to watch?

The youth vote is a key element. Around a third of the 9.6 million registered voters are between 18 and 30. Almost half of them will be casting their ballot for the first time.

Victims of the Khmer Rouge are remembered in the Tuol Sleng Genocide Museum

These young voters will have no memory of the terrible years of Khmer Rouge rule from 1975-1979 when up to two million Cambodians died from starvation, overwork and targeted killings.

The CPP has historically promoted itself as the saviour of the country from this dark period, but this may no longer be a meaningful message for many voters.

Observers have noted that unlike campaign periods in the past, there have been no violent clashes so far between rival youth camps.

What part do the media play?

The ruling party has almost total control of TV and radio.

Early in the run-up to the election, the government banned foreign radio broadcasts from the airwaves during the month-long campaign period, but it later reversed its decision.

However, a separate ban remains in place on election-related foreign broadcasts in the five-day run-up to the polls.

Social media therefore will be important for the opposition, especially as it is targeting urban youth.

What else may hamper a fair poll?

In addition to the CPP's media dominance and the lack of strong competing candidates, this election also has problems with its electoral roll, according to the National Democratic Institute, a US non-profit organization.

It said that 10% of registered names were bogus. Furthermore, the names of 11% of people who had registered legitimately did not end up on the list, so they will not be able to vote, the institute said.

BBC Monitoring, external reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. For more reports from BBC Monitoring, click here. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter , externaland Facebook, external.

- Published22 August 2023

- Published19 July 2013

- Published12 July 2013