Vietnam: Where saying 'I love you' is impossible

- Published

Bill Hayton was the BBC's correspondent in Vietnam until he fell foul of the authorities for reporting on dissidents in the country and had to leave. Here he looks back at the vagaries of life in one of the world's five remaining communist-run states.

1. It's impossible to say "I love you" in Vietnamese

It isn't because the Vietnamese are not passionate. Rather, there is no word for "I" or "you" in colloquial Vietnamese.

People address each other according to their relative ages: "anh" for older brother, "chi" for older sister, "em" for younger sibling and so on. This is why Vietnamese quickly ask strangers how old they are so that they can use the appropriate pronoun and treat them with the correct amount of respect.

So a typical declaration of love might be: "Older brother loves younger sister." If, however the woman was older, it would be: "Older sister loves younger brother." But it has to be said that women often prefer to be called "em", regardless of their age.

There are more than 40 different pronouns describing the relationships between individuals and groups of different ages and positions. Most sound a lot better in Vietnamese than in English.

2. Vietnamese national dress is inspired by 1920s Paris fashion

Images of Vietnamese women with their long black hair and beautiful silk dresses flowing in the breeze, gracefully riding bicycles, have sold millions of postcards and paintings.

The outfit, the ao dai - pronounced ow zigh - is de rigueur for women on formal occasions or if they are working in hotels or hospitality. But while the origins of the ao dai date back to dresses worn by women in the 18th Century, its modern form can be traced to Paris fashion of the 1920s, when Vietnam was part of French Indochina.

Nguyen Cat Tuong, a French-trained fashion designer at the Indochina School of Fine Art in Hanoi, redesigned the style in 1925 to try to modernise the image and role of Vietnamese women. It was promoted as a national costume and became very popular in the 1950s and 1960s in southern Vietnam, where it has been more common than in the north.

At times condemned as decadent by the Communists, it was rarely worn during the postwar period but is now back in favour.

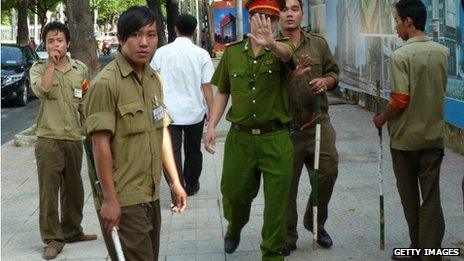

3. One in six is employed by the security forces

Vietnam is not the police state that it used to be only a few years ago, but that doesn't mean that no-one's watching you.

There are several security services seeking out signs of subversion. Apart from the regular army and police force there are paramilitaries, village militias and, in cities, neighbourhood wardens to keep an eye on what everyone is up to. They all report to either the Ministry of National Defence or the Ministry of Public Security.

One of the most authoritative observers of the Vietnamese military, Carl Thayer of the Australian Defence Forces Academy, has estimated the total size of Vietnam's various security forces as at least 6.7 million.

Given that the country's total working population is around 43 million, that suggests that one person in six works either full or part-time for a security force

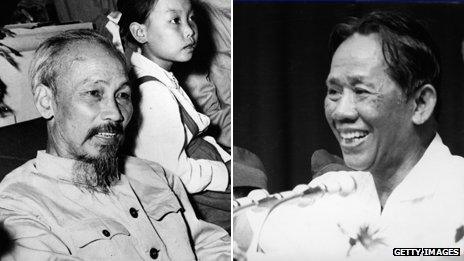

4. The father of Vietnam's revolution was just the front man

"Uncle Ho" was the poster boy of the Vietnamese revolution and his picture still adorns posters, banknotes and much else in Vietnam. But recent research has revealed that Ho Chi Minh (whose real name was Nguyen Sinh Cung) was not really in charge of the (communist) Democratic Republic of Vietnam during the 1960s at the height of the conflict with the United States.

During the 1910s Ho had been a migrant worker in France and London where he washed up in the Carlton Hotel, among other jobs, before becoming a communist and travelling to Russia and then China.

He fought against the Japanese in World War II and then against the French before becoming president. He was chief bogey man for the US during the war.

But there has long been a debate about whether he really was a hardliner.

According to the latest research, real power was held by the general secretary of the Communist Party, Le Duan, a brutal, uncharismatic Stalinist.

Le Duan used his control over the security services to keep other leaders in check and overcome opposition to his strategy of fighting an all-out war against the Republic of Vietnam in the south of the country.

Victory in 1975 left Le Duan in charge but with terrible consequences. Revenge and economic mismanagement left the country isolated and impoverished.

His death in 1986 paved the way for an opening-up of Vietnam.

5. Industrial-scale slaughter

In 1946, on the eve of war with France, Vietnam's Communist leader Ho Chi Minh warned Paris: "You can kill 10 of my men for every one I kill of yours, but even at those odds you will lose and I will win."

He turned out to be right about beating the French. However, after they left and were replaced by the US, the ratio of deaths inflicted on the Vietnamese by US forces was an estimated fifty to one - five times greater.

The number of US military personnel killed in Indochina between 1955 and 1975 is known almost exactly: 58,220, though 1,629 are still listed as missing in action. However, no-one knows exactly how many Vietnamese were killed.

One estimate published in the British Medical Journal in 2008, based on a statistical survey, suggested that three million Vietnamese were killed in those 20 years.

The official Vietnamese estimate is three million dead, including two million civilians. The huge numbers reflect the battle between the Vietnamese Communists' determination to win and the ruthless tactics and industrial-scale firepower deployed by the United States.

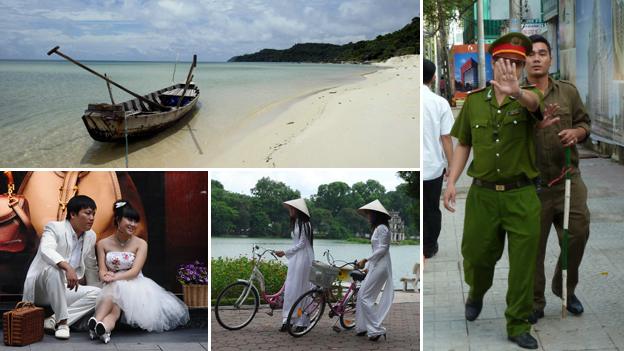

6. Vietnam's tourist islands were once gulags

"The hidden charm" is Vietnam's seductive tourist slogan. Many Vietnamese do not like it, but it teases foreigners' yearning for adventure and discovery.

Among those discoveries are the beautiful islands of Phu Quoc and Con Dao. But behind the palm-fringed beaches lie painful histories.

Con Dao was a colonial Bastille where the French colonialists imprisoned political prisoners and rebels from the 1860s until the 1950s. Con Dao was infamous for its "tiger cages", holes in the ground measuring 1.5m (5ft) x 3m each holding up to five shackled prisoners. It remained a jail under the southern Republic of Vietnam.

Some 20,000 people are thought to have died there.

Phu Quoc was also the site of a French prison that became a Vietnamese one, often supervised by American interrogators.

After the war the island hosted camps where opponents of the Communist Party were sent for harsh "re-education". The isolation once made both islands ideal places for repression. Now it makes them ideal places for a restful getaway.

7. Vietnam's long-standing enemy has always been China

Although the war finished nearly 40 years ago, most foreigners still associate Vietnam with its conflict with the United States. But Vietnamese have fought wars with China for much longer.

Although there are many similarities between Chinese and Vietnamese culture, modern Vietnamese more or less define themselves in opposition to China.

Every city features roads, statues and buildings named after heroes (real or mythical) who fought the people from the north.

These include: Hai Ba Trung, the two Trung sisters who led a rebellion in AD40; Ngo Quyen, whom Vietnamese regard as leading them to independence in 938; Ly Thuong Kiet, who fought the Sung in 1076; Tran Hung Dao, who defeated the Mongols in 1284; Le Loi/Le Thai To, who defeated the Ming in 1428; and Nguyen Hue/Quang Trung who defeated the Qing in 1789.

Most of this is anachronistic myth since these earlier conflicts were between regional rulers, rebels, warlords, proteges and upstarts who would not have understood the meanings of such terms as "Vietnam" or even "China" for these are modern inventions.

These days tensions bubble away over a long-running territorial dispute with China over parts of the South China Sea, rich in oil and fish.

8. Not all war relics are what they seem

The picture of the Communist tank crashing through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon and parking on the lawn gave the English language a new phrase.

But which tank was it?

Museums in both Hanoi and Saigon have tank number 843 on display with claims that it was the tank that was first through the gates. However, pictures from 30 April 1975 suggest that Tank 843 was not the first one through the gates at all.

Tank 843 got the glory, it is believed, because it was the one used in a re-enactment staged for the movie cameras immediately after the real event. War relics like these are still very important for the Communist Party whose legitimacy depends, in part, on its role in "liberating" the country.

9. If you love someone, burn their possessions

In traditional Vietnamese religious belief, death does not mean the end. The dead just move on to an afterlife in which things are the same as in the living world.

The dead therefore need their home comforts as much as the living. But how do they obtain mobile phones, washing machines and new clothes?

Simple. Their living relatives buy paper effigies of the items and simply set fire to them and the objects are transferred to the afterlife in the smoke.

The Vietnamese government estimates that people spent around $20 million buying paper objects to burn last year.

10. Half of Vietnamese share a surname few foreigners can pronounce

From Hanoi to Hollywood, tens of millions of Vietnamese share one surname: Nguyen.

The prime minister is Nguyen Tan Dung; there is a Vietnamese-American actor, Dustin Nguyen; and Nguyen is already on the lists of most popular surnames in the US, Australia and several European countries.

Pronunciation is fiendishly tricky for foreigners with the combination of "ng", tricky vowels and unfamiliar tones. The best that most of us can manage is "nwee-yen" or even just "win".

The name is probably derived from a Chinese root. Over many centuries, thousands of families chose - or were forced - to change their name to Nguyen as a sign of loyalty to successive Vietnamese rulers.

As a result not all Nguyens are the same. Some may be the children of former emperors, others the offspring of former rebels.

11. Very few Vietnamese can read their historic language

Until the early 20th Century, Vietnamese was usually written in Chinese-style characters, known as Chu Nom. But as early as the 16th Century the language had also been written down in a Western script by Portuguese Christian missionaries and then by a French Jesuit priest, Alexandre de Rhodes.

The missionaries simply wanted a way to preach the Christian gospel more easily but in the 20th Century Vietnamese nationalists realised that the script made it easier to spread their ideas too. Latin script was much easier to learn than the characters of the old language.

Nowadays, Chu Nom has almost died out. The only places you are likely to see it are on the inscriptions around Buddhist pagodas. Very few Vietnamese are able to read them or the country's historic documents, such as Vietnam's best-known piece of early literature, the Tale of Kieu.

A few experts keep the knowledge alive but they are desperately worried that this language is about to become extinct.

About the author: Bill Hayton was the BBC reporter in Hanoi in 2006-7 and his book Vietnam: rising dragon was published in 2010. He has not been back to Vietnam since 2007.