Viewpoint: Can Australia's Rudd pull off a miracle?

- Published

Australians vote for their next leader - Kevin Rudd or Tony Abbott - on Saturday

With a handful of days until Australia's election, former Sydney Morning Herald editor-in-chief Peter Fray assesses the national mood - and asks whether Kevin Rudd can possibly pull off a win.

A week from now, Kevin Rudd will discover if he will be remembered as the Australian prime minister who twice won and twice lost the leadership of his nation.

If voters reject him and his ruling Labor party on 7 September, the electorate will have decided against Rudd only once, however. His own party did the other half of the job.

Nothing much is looking positive for Mr Rudd and Labor: the polls point to a loss, Rupert Murdoch's press ridicules him on a daily basis and the party's pitch that started positive - about re-shaping the economy to deal with the end of the mining boom - has rapidly shifted to the negative.

Labor is trying to scare its way back into office. The nation, it seems, is readying for change. The conservative Coalition, lead by Tony Abbott, will reclaim power six years after Mr Rudd defeated Mr Abbott's political mentor, John Howard. Or so it all seems.

But could Kevin Rudd, knifed by his own party in 2010 prior to that year's election, pull off a miracle? Several factors lead to a firm no, a handful to a very slim yes. Here they are:

Kids or grown-ups?

Australian political history is littered with rejected, written-off and resurrected leaders. John Howard (Coalition) and Paul Keating (Labor), the prime ministers immediately prior to Mr Rudd, were each considered defeated either by their own parties, voters or both in their time.

They each returned to glory: Mr Keating winning against all odds in 1993; Mr Howard reclaiming first his own party's leadership after twice losing it - and then winning four elections.

But Mr Rudd is something else again. To recap: he wins the 2007 election but, prone to micromanaging, he rapidly drives his ministers, his party and the bureaucracy mad.

Whispers start. The polls slump, he loses his nerve on key policies, he loses face at the Copenhagen climate conference. Business gets offside; as if waking from a dream, his party reminds itself that Mr Rudd, a diplomat by training, isn't really one of them.

With the backing of party machine men, his deputy, Julia Gillard, knifes him in June 2010.

Barely has the country had time to digest its shock and anger at the removal of a sitting prime minister by means other than public ballot, when Ms Gillard, Australia's first female prime minister, sets off on the election trail.

She performs poorly. So much so that - at the height of the campaign - she promises to be more like herself, to show voters the "real Julia". The country is confused and disappointed.

Labor falls over the line after election day, eventually claiming sufficient seats to form a minority government with the Greens and a handful of independents.

Julia Gillard ousted Kevin Rudd - but the public didn't like it

The subsequent parliament is productive but chaotic. Mr Abbott says no. A lot. Everyone squabbles. Politics gets very personal. Voters turn off. Parliament looks more like a kindergarten.

As John Chalmers, group communications manager for media intelligence company iSentia notes, the "public disliked immensely" the personal attacks on Ms Gillard and Mr Abbott, and "the leadership challenges by Rudd".

Both sides suffer but, being in power, Labor bears the brunt. Three years on, as her poll numbers slump, and key policies founder, the Labor caucus knifes Julia Gillard and brings back Kevin Rudd.

Again, allowing voters little time to think about what has happened, and having ditched or amended several key Gillard policies, Mr Rudd heads to the polls.

And where has that got the Australian electorate? Confused (again), anxious and, I suspect, ready to give someone a big bloody nose.

Geoff Kitney, an astute Canberra-based political journalist, writing in the Australian Financial Review, says voters "want a return to some peace and quiet in politics".

In other words, they want grown-ups, not squabbling kids. He's right.

A question of trust

Political in-fighting has hit public trust in leaders, experts say

The Australian Electoral Study (AES) at the Australian National University, external has been tracking attitudes to politics and politicians since 1987. It has a powerful and effective method: it surveys voters' attitudes after the election, thus removing much of the noise inherent in the campaign.

In 2007 and again in 2010, Kevin Rudd was rated the most popular politician in the country. In 2007, Mr Rudd's score (dislike v like) beat the high recorded in 1987 by legendary Labor populist Bob Hawke; in 2010, when he wasn't even party leader, Kevin Rudd beat both Julia Gillard and Tony Abbott.

Mr Rudd was seen as competent, smart and compassionate. But now the magic has worn off. As the study's co-author, Ian McAllister, says, "trust declines". "As a new person emerges trust increases, and as we get to know them, trust declines."

Trust is not the same as like, especially in this Facebook world, but it is a vital ingredient of victory.

Further complicating the outlook for Mr Rudd - and whoever follows him - is that voters appear less likely to trust their representatives across the board.

The AES shows that Australians have been losing trust in their MPs for decades.

The combination of this underlying trend with the chaos and bloodletting of the past few years do not augur well for Mr Rudd and Labor.

Let's blame Rupert

Rupert Murdoch has made it clear he does not want a Rudd victory

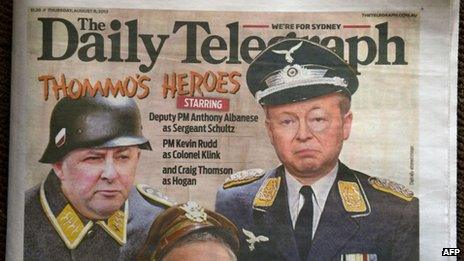

Rupert Murdoch and his editors, who control the key mastheads in every Australian city aside from Perth, have got it in for Kevin Rudd and Labor. In Sydney (The Daily Telegraph) and Brisbane (The Courier-Mail), in particular, the Murdoch tabloids have been running hard and hot against Labor in general and Kevin Rudd in particular.

This is no big secret and, for all the distaste such actions leave, Murdoch editors have every right to advocate and campaign.

Of greater concern for Labor is that with Murdoch tabloids leading the charge, and talkback radio not far behind, Kevin Rudd is becoming a subject of national ridicule. His every character flaw or perceived character flaw is being amplified tenfold: he is rude, he is vain and he is fat. It is open season on the prime minister.

If the Coalition thinks this will happen only to Labor people, they should think again.

But for now, the Murdoch media is doing a fine job of contributing to the general negative vibe around Labor and its management of the country.

That is a tried and tested way of pulling voters away from progressive parties to the supposedly safer hands offered by the conservative side.

Is Abbott 'normal'?

Tony Abbott is ahead - but voters are not quite sure what to make of him

London-born, Oxford-educated Tony Abbott could soon be measuring the curtains at the Lodge, the prime ministerial residence in Canberra, the nation's capital.

But there's a catch: as the polls indicate, the country is not fully sold on Mr Abbott's character, nor feels at ease about his capacity to lead.

For all his woes, Kevin Rudd remains in front as preferred prime minister, though the gap has narrowed. Tony Abbott is not a warm politician. A devout Catholic in an increasingly non-believing nation, he is pugnacious and at times, brittle.

His picture opportunity of choice sees him undertaking strenuous, punishing exercise. He runs, he rides, he swims - but does he have a beer with his mates afterwards? Does he have mates? Of course he does.

But the nation is a little unsure if he's "normal", one of us. The mean-minded may jump to the - wrong - conclusion that all those long-distance bike rides are an exercise in self-flagellation. Why does he need to punish himself so? What's he done so wrong?

Certainly, as opposition leader he's done a lot of opposing. He would argue that is his job, to hold the government to account. That is obviously true.

But it is also true the nation's negative mindset about the government has rubbed off on Mr Abbott and his side of the chamber. And Tony Abbott's relentless negativity only serves to make that perception stick.

That may well all change if Tony Abbott takes control of the country next week. Incumbency is a powerful thing. My guess is that Australia will warm to Mr Abbott, but never to the same extent as it did to John Howard.

But in the campaign's dying days, Labor can be expected to beat up on Abbott more and more, if only to see if he will crack.

He may, but it's a long shot.

Will the young save the party?

Do Labor's hopes lie with young undecided voters?

Labor's best hope of saving a heap of seats may yet rest with younger voters, a volatile voting bloc that represents more than 26% of the electorate.

Research by the Whitlam Institute, external, a group within the University of Western Sydney, identifies younger voters as the potential flag carriers of a new "fluid electorate".

Distinct from the more traditional swinging voter, authors Ron Booker and Eric Sidoti see these 18-24-year-old voters as permanently unaligned and developing "electoral habits of their own making".

Whether such a grouping can be mobilised to save Labor and Kevin Rudd would appear unlikely. But it is largely true that Labor has won the social media battle, and Mr Rudd's penchant for "selfies" with any voter within two metres holding a smart phone, may give him an edge over Mr Abbott.

Again, this is a long shot.

Post-match analysis

Labor was once privately and publicly admired for its win-at-all-costs approach to politics. The party was tough and successful. Now it has been infected by what looks like a killer virus.

Kevin Rudd was supposed to give Labor a chance to save the furniture and yet he appears to be using the same woodwork to build Labor's funeral pyre.

Julia Gillard is not contesting the election and neither are several of her former ministers.

With such a turnover in talent, this election will be a watershed for Labor, irrespective of the result.

Defeat will serve to sharpen the post-election critiques of where it all went wrong. The first implement to hand should be a mirror.

Peter Fray is the editor-in-chief and founder of PolitiFact Australia, a fact-checking website dedicated to politics. He is the former editor-in-chief and publisher of the Sydney Morning Herald.