Australia: Why boat people risk it all

- Published

A boat carrying asylum seekers spotted off Indonesia sailing towards Australian waters

Every month, thousands of migrants undertake a perilous journey across the Indian Ocean to try to reach Australia's shores.

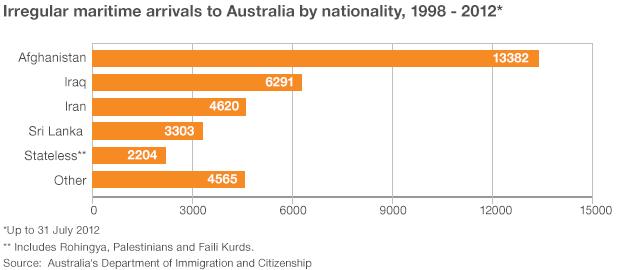

Many are fleeing troubles in countries like Afghanistan, Iran and Sri Lanka.

They pay huge sums to people smugglers, who operate often unsafe boats out of Indonesia.

The issue of asylum seekers has been prominent in the Australian general election campaign, with both main parties pledging tough policies to stop the influx.

The BBC has spoken to three migrants at different stages of their journey.

Leaving Afghanistan

Habib is a 41-year-old civil rights activist in Kabul. He has three daughters aged nine, eight and three. He and his family are hoping to leave Afghanistan any day now.

Asylum seeker: "I don't have any other way out".

I have done a lot of work defending the rights of people affected by violence. Because I've taken cases through the courts, I have faced many difficulties.

I have been jailed three times and I have been attacked twice. The second time I was stabbed - they tried to kill me.

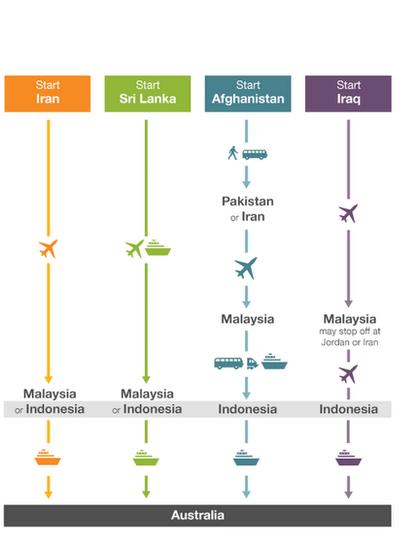

Typical routes used to smuggle people to Australia, Source: Australian Crime Commission, 2013, UNDOC, Jan 2013

I realised that if I died my wife and three girls would face a very dark future. So I decided to leave Afghanistan.

I chose Australia because it's a country that cares about human rights.

I want my girls to be able to go to school somewhere peaceful where they won't hear news of violence, suicide bombs and murders at every moment.

I have some relatives living in Indonesia. They put me in touch with a travel agency in Kabul which is in contact with traffickers.

I haven't met the traffickers myself, but the agency says we will set off very soon.

It's a big gamble of course. A trafficker is not a person who can be trusted. But these people have already helped our relatives leave and we don't have any other choice, so we have to trust them.

We've been told that first we have to go to India. Then they will move us to Malaysia and then on to Indonesia.

We have to pay them $21,000 (£13,500) to get us Malaysian education and work visas. It is $6,000 each for my wife and I, and $3,000 each for our children.

We have to pay half of it before the journey and the rest after arriving in Malaysia. It's a struggle to find that kind of money.

I've had to borrow some, and we're selling all our possessions and household goods to cover the rest.

We've heard the reports on TV and on the radio about how dangerous the boat journey from Indonesia to Australia is. The boats aren't seaworthy, they overload them and many of them sink.

But despite this, we see that most asylum seekers do reach Australia and start new lives there.

We're ready to accept the difficulties in order to reach a place where we will have a peaceful life.

I have to leave my country to protect my life and build a better future for my children.

It makes me sad because I was born here and the graves of my parents are here. But I don't have any other way out.

An Iranian boy on a boat intercepted in Indonesian waters while sailing to Australia

Detainee on Christmas Island

Said, 23, is from the Iranian capital, Tehran. He comes from a middle-class family but he decided to leave after converting from Islam to Christianity, a criminal offence in Iran. Said made the journey by boat from Indonesia to Christmas Island. He landed just three days after new rules came into effect stipulating that all new arrivals will be sent to Papua New Guinea for processing, and that if they get refugee status, they will not be allowed to resettle in Australia. It has left him feeling desperate. He spoke to the BBC from the detention centre on a mobile phone.

I fled Iran in search of freedom for my faith. I would have never chosen Australia if I'd known about this new situation.

My three-day journey on the boat was horrifying. I saw death in front of my eyes.

Everybody risked their lives to get here - but now [the authorities] say: 'We don't care how you arrived here, you will have to go to Papua New Guinea whether you like or not.'

We are being forced to go to PNG and this is unfair. I am really depressed.

I was the only child in my family, and we didn't have any financial problems in Iran.

If they send me to PNG, I will commit suicide there. My parents won't ever see me again.

Asylum seeker in Australia

Maarouf Mashfee Sharief is a 38-year-old Sri Lankan Muslim. He decided to leave last year after receiving threats when he stood in local elections.

Sri Lankan asylum seekers in Indonesia rest after being rescued by local fishermen

Australia was not my first choice of destination - that would have been Italy. But my idea was to get out of the country as soon as possible as I felt very insecure at that time.

I learned through business contacts that someone was organising a boat to Australia.

When I went to meet the main guy, he was really reassuring.

I was sort of aware it could be dangerous, but he said it would be safe and quite comfortable.

Everyone was charged one million Sri Lankan rupees ($7,500; £4,800), which I was able to raise in three days.

I did have a little money of my own, but most of it came from loans from friends.

The journey was much more dangerous than I had imagined. We were taken out to sea in a fishing boat and then transferred to a larger vessel with others on board. It was meant for just 40 but in all, there were 117 people.

Those in charge would only give you food once a day, and there was never enough for everyone.

It was down to luck whether you got any food or not. The drinking water ran out after 10 days. I can honestly say I did not know whether I would live or die.

I had no idea where we were as all we could see was water.

On the 17th day, we spotted land and told the crew. As we drew close we were intercepted by an Australian navy vessel.

We came to know it was the Cocos Islands, controlled by Australia.

This place is just a tourist destination, and does not have detention facilities so after a few days we were sent to Christmas Island.

While I was there I developed a chest infection, and I was moved to Perth for treatment.

Normally, asylum claims would be processed on Christmas Island. You would only get to the mainland if they believe you may have a genuine asylum claim.

Now I am in Melbourne awaiting the result of my asylum claim.

All my family and friends are in Sri Lanka. It was very difficult to leave them, but I am convinced my case is pretty strong, and if it is accepted I can bring my family over.

In Sri Lanka, I was reasonably well off as I was a businessman. I had my privacy and freedom. Here, I am living with three or four other Sri Lankans, surviving on benefits.

I would like to humbly say to my fellow Sri Lankans: 'Don't make this journey, and don't believe the assurances given by the people traffickers. They just benefit from our misfortune.'

Maryam Ghamgusar, Fariba Sahraei, Kumar Malhotra, Jenny Norton and Johannes Dell contributed to this article.