Afghanistan election: Warlords and technocrats seek to replace Karzai

- Published

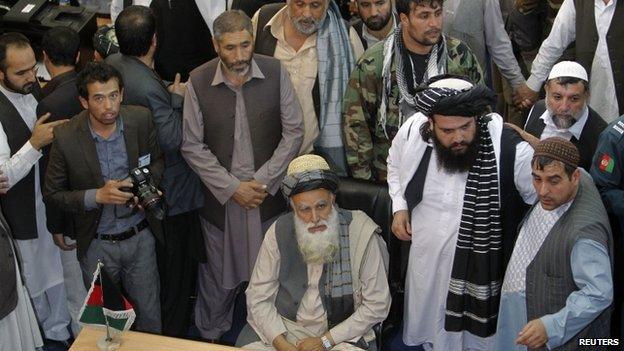

The most controversial candidate is former guerrilla leader Abdul Rasul Sayyaf (seated, centre)

The race to succeed Afghan President Hamid Karzai in next April's election looked wide open as nominations closed on Sunday night.

Twenty-two people have been nominated, and new rules, including the requirement that potential candidates show the support of 100,000 voters, have not deterred those with little hope of success from entering the race.

There are six serious candidates, most of whom were prominent in the years of the civil war before the Taliban defeated them in 1996. It is as if all the 2001 war did was to overturn the result of that last conflict, rather than creating new politics.

The most controversial candidate is Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, who invited Osama Bin Laden into Afghanistan in 1996, and was described by a US investigation as the mentor of the 9/11 mastermind, Khaled Sheikh Mohammed.

After studying in Cairo, where he was influenced by the Muslim Brotherhood, he was one of the founding fathers of the Islamic fundamentalist movement in Afghanistan in the early 1970s, going on to lead a guerrilla group financed mainly by Saudi Arabia in the war against the Russians in the 1980s.

He has been an MP in the new Afghan parliament, which passed an immunity law to block prosecutions for past crimes, but now he is a presidential candidate his former life will come under intense scrutiny. Several investigations, including one from Human Rights Watch, have alleged that he was responsible for war crimes in the early 1990s.

One of Mr Sayyaf's vice-presidential running mates is another ex-warlord, Ismail Khan, who recently called for the former mujahideen militias to be re-armed to fight the Taliban, for what he saw as an inevitable civil war next year.

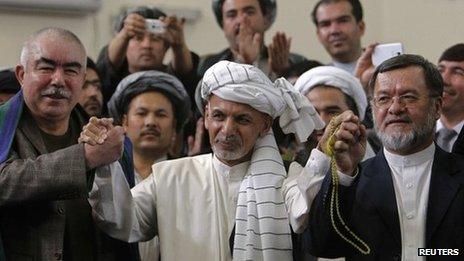

Ashraf Ghani (centre) has Gen Dostum (left) as a running mate

Another controversial figure from the warlord years, Abdul Rashid Dostum, is the vice-presidential running mate of Ashraf Ghani - a former finance minister, who otherwise had cultivated a reputation as an anti-corruption technocrat.

The emergence of Mr Sayyaf, Ismail Khan and Gen Dostum in the presidential election will be highly unwelcome among international donor nations who have expended huge amounts of money and lost lives to stabilise Afghanistan.

Norway has this week cut some of its aid programme because of Afghanistan's failure to deal with corruption, or significantly improve the rights of women, and other donors could follow suit. Both the UN and EU need to sign new agreements in the next year, and both will be seeking assurances that Afghanistan deals with crimes committed during its long conflict.

Zalmai Rassoul has a female governor on his ticket

The former foreign minister, Zalmai Rassoul, a descendant of Afghanistan's royal family, also needed to turn to a former warlord clan for one of his running mates to build support, but in a historic move, his other vice-presidential nominee is the reformist governor of Bamiyan province, Habiba Sarobi, the first woman to be nominated for high office in Afghanistan with any chance of success.

Also in the race is a former senior mujahideen commander Gen Abdul Rahim Wardak, a career soldier, and one of a small number of Afghan soldiers to be trained in the US in the early 1970s. He was one of the most successful commanders in the war against Soviet occupation, but withdrew when the mujahideen fought among themselves after the fall of the Soviet-backed government in Kabul in 1992. He told the BBC: "I never killed fellow Afghans; I do not have blood on my hands."

He has been responsible for building the new Afghan army, first as deputy defence minister, then as defence minister since 2001.

With no natural successor to Hamid Karzai, Abdullah Abdullah is the man to beat

The rush of candidates in the hours before the polls closed showed the feverish deal-making that was required. But the close runner-up in the 2009 election, former foreign minister Dr Abdullah Abdullah, confidently filed his nomination papers some days ago.

Dr Abdullah was close to the legendary guerrilla commander Ahmad Shah Masood, who was killed in 2001, and while he has not succeeded in gaining the support of Masood's brother, who is on the ticket of the other former foreign minister Rassoul, he has wide support from other significant Afghan leaders.

After widespread reports of corruption during the last election, Dr Abdullah made this promise in a BBC interview: "I will make sure the people of Afghanistan have what they want - free and fair elections."

Qayum Karzai has shown little interest to date in politics

The last of the serious candidates to emerge was the president's brother, Qayum Karzai, a businessman, who has shown little interest in politics, and was criticised for rarely attending parliament when he was elected for one term. He, Ashraf Ghani and Zalmai Rassoul will be competing as the natural successor to President Karzai, and it is unlikely that all will still be in the race by election day next April, but each would exact a price for standing aside.

Afghanistan's election commission will now scrutinise the applications, and hear any complaints before the list is finally closed on 17 November.

With no agreed candidate running as the natural successor on the president's side, the man to beat remains Dr Abdullah. But on the way to the nomination Ashraf Ghani received the blessing of Sibghatullah Mojaddedi, the head of what was once the king-making clan in Afghanistan - in the days when Afghanistan had kings.

Ashraf Ghani is well known internationally for his work as an economist in developing countries. He polled very badly in the last Afghan election in 2009, but has raised his profile as head of the process of transition from US-led military control, making 140 visits to Afghan provinces.