Diabetes: Asia's 'silent killer'

- Published

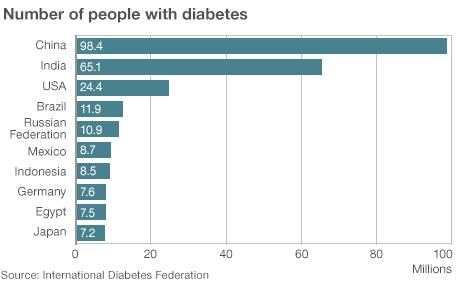

China has the greatest number of diabetics in the world, according to the IDF

Asia is in the grip of a diabetes epidemic.

In human and financial terms, the burden is huge and it is hitting the poor especially hard.

Often thought of as a disease of the rich, experts say the unabating rise may be fuelled as much by food scarcity and insecurity as it is by excess.

Changing lifestyles, rapid urbanisation and cheap calories in the form of processed foods are putting more and more people at risk of developing Type-2 diabetes.

There are now 382 million people worldwide living with diabetes, according to new figures from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF), external.

More than half are in Asia and the Western Pacific, where 90-95% of cases are classed as Type-2.

China is leading the world, with the disease now affecting more than 98 million people or about 10% of the population - a dramatic increase from about 1% in 1980.

Prof Juliana Chan of the Chinese University of Hong Kong says there is a complex interplay between genetic, lifestyle and environmental factors, which have been compounded by China's rapid modernisation.

"Diabetes is a disease of paradoxes," she says.

"It is typically an ageing disease, but the data shows that the young and middle-aged are most vulnerable. It is prevalent in obese people but emerging data suggests that for lean people with diabetes the outcome can be worse."

The big question is whether China has the capacity to deal with a health problem of such magnitude.

China spent $17bn (£10.6bn) on diabetes last year. The disease may consume more than half of China's annual health budget, if all those with the condition get routine, state-funded care, the IDF says.

"Diabetes is a silent killer in a silent population," says Prof Chan.

Men and women, trapped by stigma, poverty and misinformation, often do not seek help for diabetes until it is in its advanced stages.

Kidney failure, cardiovascular disease and blindness are common complications.

Prof Chan says China's leaders need to do a lot in terms of public health policy.

"One of the greatest challenges is that the system is not conducive to preventative care. We need to go out and find those at risk otherwise you miss the critical moment to prevent the disease," she says.

Governments are waking up to the problem, according to Leonor Guariguata, a biostatistician at IDF.

"India and China are uniquely positioned - as they are developing so fast, they have the resources to act fast and reframe their health systems," she says.

Big babies

India is closely trailing China, with an estimated 65.1 million diabetics.

Kanmani Pandian is 25 years old and expecting her first baby in January.

All pregnant women in Chennai undergo compulsory testing for diabetes

Two months ago she was diagnosed with gestational diabetes - a disease she had never heard of.

Kanmani was lucky. In Chennai, in the south-eastern state of Tamil Nadu, universal screening is available for pregnant women.

If left unchecked the disease can lead to life-threatening complications, including foetal macrosomia, or excessive birth weight, making the delivery dangerous for both mother and child.

More than 21 million live births were affected by diabetes in 2013. In India, the condition is particularly prevalent.

Dr R M Anjana, a diabetes expert based in Chennai, says gestational diabetes is often not taken seriously "because people think it's a one-time thing or a mild affliction".

The condition disappears after birth, but within five years of pregnancy, 70-80% of women develop Type-2 diabetes, she says.

The infant is also at increased risk of developing the disease in later life.

'Owning up'

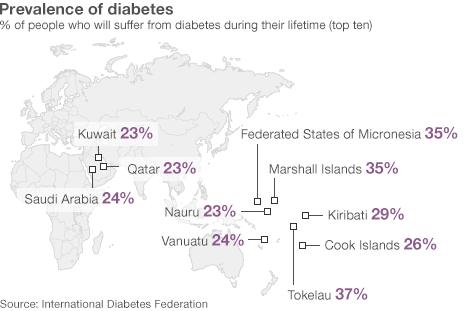

Across the Western Pacific the disease is taking an unprecedented human and economic toll.

In Fiji, surgeons carry out a diabetes-related amputation, external every 12 hours on average.

"Before people seek help for foot infections they would have tried traditional medicines and herbs. By the time they come to the clinic the infection is often so advanced they need an amputation," says Dr Wahid Khan, co-founder of the Diabetes Trust of Fiji.

"People don't want to own up to having diabetes. Culturally, it's seen as an illness that leads to early death. If it's known the person has diabetes there is less chance of them getting a job for instance," Dr Khan says.

One in three people in Fiji aged 30 or above has diabetes.

"The writing has been on the wall for a long time," says Dr Khan.

Following the trend across Asia, Fiji's economy, driven by tourism, the sugar industry, gold, copper and fish exports, has produced a rising middle class.

"People would traditionally grow their own crops, catch their own fish, if you wanted to get anywhere you would have to walk. We've become more lazy and less active," says Dr Khan, adding that he also has a gripe with the confectionary and fast food industries.

In Fiji, diabetes could be prevented or delayed in 80% of cases through simple lifestyle changes, says the IDF.

Three diabetes "hubs" were opened earlier this year, and Dr Khan is urging all adult Fijians to get screened.

As part of a "massive campaign" to begin in 2014, Dr Khan says surgeons will be asked to "save rather than cut" when it comes to amputations, which are often seen as preferable to keeping patients in hospital for prolonged periods of time.

"There is no one answer to diabetes," says Dr Khan, "but we are striving for the right path."

Additional reporting by the BBC's Shilpa Kannan in Delhi.