Scrawling messages of survival from Tacloban

- Published

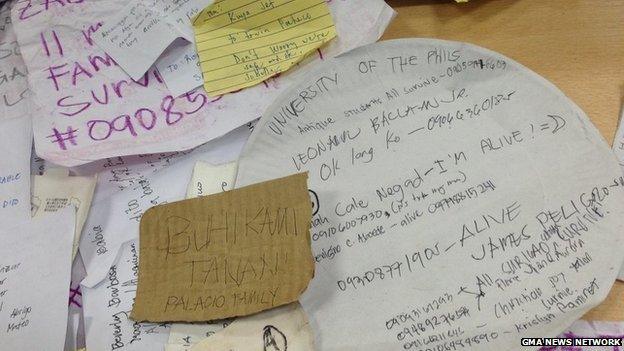

One survivor of the horrifying storm to hit the central Philippines simply wrote "Alive" on a paper plate and gave it to a journalist along with his name.

A picture of that plate and other anguished pleas handed to reporters on scraps of paper and card has been posted on the GMA News network , externaland circulated on social networks.

Another young woman looking for her two missing toddlers was photographed by a journalist who posted the picture on Twitter, external. Abigail Castinos was pictured carrying a toy for her children, missing since the storm hit.

Reporters who were in Tacloban at the time ventured out afterwards and found, amid the devastation, people with no way of communicating to the world and desperate to reach their relatives. They plied journalists with their details, begging them to take messages to their loved ones.

Survivors' pleas

With fears that up to 10,000 people may have perished in Tacloban city alone, as Typhoon Haiyan cut a ruthless swathe through the central Philippines, survivors have struggled to get messages out.

One of the first reporters on air after the storm was Jiggy Manicad of GMA News. He walked for six hours to the nearest satellite point in Palo Leyte to file a live report describing the destruction.

As he filed his piece, the camera panned across the stunned faces of people gathered around him who had survived the storm.

"I asked the people to talk directly to the camera. They said who they are and who their relatives are and how they wanted to reach out to them," Mr Manicad told the BBC by phone on his return to Manila.

On the long journey back to Tacloban he was inundated by other survivors who had scrawled details of who they were, where they lived, who their relatives were and begged him to get in touch with them and let the world know they had managed to come through the worst.

Messages read: "I am alive"; "Don't worry we are OK", "Auntie, we need help! Please! We are okay but the house is destroyed".

Reporter Erel Cabatbat posted this on his Twitter feed: "We are safe - if you know Esmeraldo Salvia of Cebu, please tell him that Gina & Liansy [pictured] are alive and well."

In the airport at Tacloban a conveyor belt has been turned into a makeshift dinner table

Erel posted this message to let a relative know that Jila, Alexa and Jude were safe and on their way to Manila

Abigail Castinos has been looking for her two missing children since the weekend

"They were giving me pieces of paper from whatever they could find, just to be able to write those messages. They even wanted to write on a little box I was carrying... I collected all and when I had a chance to do a live report again I showed the faces of the people who wrote these messages on camera.

"Eventually we were able to scan in and type up these messages and post them online."

These were the lucky ones and Mr Manicad says he has already had some feedback from relatives able to make contact.

Mr Manicad was in the city, which he says was in the eye of the storm, and realised this could be one of the worst experiences of his life.

"I was looking at the ceiling of our room and waiting for it to be sucked up. I had an idea that the devastation would be immense but we couldn't see anything because of the rain water and the gusts of wind."

He said ships out at sea were blown way off course and described how palm trees were lifted up like toothpicks. Afterwards they picked their way through flooded streets where they found dead bodies lying near the gutter, vehicles overturned and corpses of pigs, dogs, rats everywhere.

"Along the way people were asking if they could be interviewed so they could record their pleas for help and their messages to their relatives. I have this documentation on our camera."

Texting relatives

Erel Cabatbat, a reporter for TV5 in Manila, also found himself both reporting the disaster and helping those stranded in the city communicate with relatives.

"I have pages full of the numbers of people who begged me to text their relatives and let them know that I was OK," he told the BBC from Cebu where he is continuing to cover the crisis.

He said survivors handed him notes with numbers to text. As soon as he left the city and had coverage he sent text messages to alert their relatives.

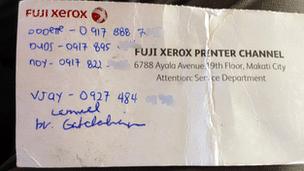

The note from the doctor who begged Erel Cabatbat to contact his relatives in Cebu

One story that stuck in his mind is that of a doctor who walked 5km (3 miles) from his home, where the ceiling and roof had been destroyed by the storm, to the airport where a makeshift shelter had been set up.

"He was so wet, covered in mud and he asked me, if I had a chance to go back to Cebu, to contact his children.

"I managed to send them text messages and posted on my Twitter account and they called me back and told me that they were coming to Tacloban to take him to safety."

Mr Cabatbat walked around the city and would film messages from other survivors. Other messages he simply posted on his Twitter account and if they gave him phone numbers he would text relatives.

"I have never experienced this in a disaster before - the overwhelming sadness and desperation to be in contact. Sometimes I feel so small because I cannot really do much. All I can do is try and communicate and reassure them that I will do everything I can to help them find their loved ones."

Erel Cabatbat took this photo to document the destruction in the city of Tacloban

"Two days before typhoon made landfall. they did not appreciate that it would be that strong. People did not anticipate it."

Outside the GMA News station in Manila, a queue of people asking for news about their relatives has formed, one editor at the station told the BBC. Their website has set up a micro-site to help people find their relatives.

Other websites such as the Philippines Yahoo news site, external are posting lists of survivors and a list of other databases can also be found online., external The congressman who represents the Tacloban area, Ferdinand Martin Romualdez, is also posting information from relatives on his Facebook page., external

But for Philippine journalists inside the devastated zones, they have both reported the news and become conduits between survivors and their relatives.

Jiggy Manicad says he is haunted by those scraps of paper scrawled with names, numbers and the state of countless families - dead or alive.

Erel Cabatbat is still posting messages from the survivors he meets.