Nasiruddin Haqqani: Who shot the militant at the bakery?

- Published

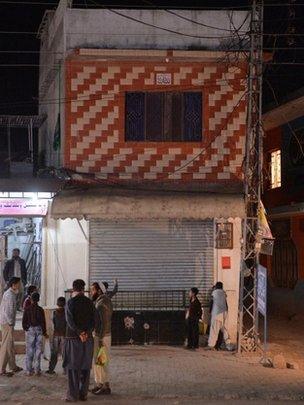

The crime scene was quickly washed down and the body taken away by police

At first it appeared as if two men had been injured in a gun attack at a bread shop in the eastern suburbs of Pakistan's capital, Islamabad - just a routine shooting, a senseless crime in a large city.

But eyewitnesses noticed a number of aberrations. Some told local press that the police who arrived at the crime scene collected bullet casings and other evidence and then washed the area down to clean away the blood stains.

One of the injured was taken to a nearby house, witnesses said. Later, the injured man - or was he dead by then? - was put in a vehicle and driven away in the presence of senior police officers.

Local police registered a report saying unknown assailants on a motorbike injured a naan-bread maker at a suburban market. When confronted by the reporters, they denied there had been a second injured man.

The capital's main hospitals also reported only one casualty from the scene - one Mohammad Farooq, the naan maker.

Haqqani family members had been living in the Islamabad area for several years

But by mid-afternoon on Monday rumours were swirling that the second mystery man hit in the attack was in fact Nasiruddin Haqqani, a key leader of the so-called Haqqani network, considered one of the deadliest Afghan Taliban groups fighting Western forces in Afghanistan.

Confirming the rumours, a relative of Mr Haqqani told BBC his body had been spirited from Islamabad to the town of Miranshah in North Waziristan - roughly six hours drive across two provinces and one federal tribal territory, all dotted with heavily-manned military and police checkpoints.

Militant's Islamabad residence

There are obvious reasons for this cover-up.

For years, Pakistan has been accused by the West of backing the Haqqani network to counter the influence of arch-rival India in Afghanistan, a charge it denies.

So the idea that some of the group's key leaders were freely moving around in Islamabad - and even had a permanent home in the city, as has become apparent following the attack - could cause the country some embarrassment, a reminder of what it faced in 2011 when al-Qaeda leader Osama Bin Laden was killed by the Americans in a Pakistani city.

Nasiruddin's father, Jalaluddin, set up the Haqqani group to fight US troops

Nasiruddin was the son of Jalaluddin Haqqani, a veteran of the Afghan war against the Soviets in the 1980s who then set up the Haqqani network to fight the Americans in the post-9/11 era.

He was also the elder brother of Sirajuddin Haqqani, who heads the Haqqani network these days.

The Haqqanis belong to the Jadran tribe which is a native of eastern Afghanistan's Loya, or greater, Paktia region, and pledge allegiance to the Afghan Taliban leader Mullah Omar.

But they have their main sanctuary in Pakistan's tribal territory of Waziristan and maintain operational independence from the Afghan Taliban.

The group is known for launching spectacular attacks against Western and Indian targets in Afghanistan.

And it is known to have played a prominent role in seeking to bring the anti-Pakistan militant groups in the Pakistani Taliban (TTP) alliance to the dialogue table with Islamabad.

Nasiruddin Haqqani apparently used the Islamabad house as a base for fundraising for the group

Nasiruddin Haqqani was not central to the group's military operations, but had a vital role as a fundraiser and emissary who frequently travelled to the sheikhdoms of the Middle East to raise cash, and also, according to some reports, to look after his family business there.

He also played a part in last year's efforts to set up a Taliban office in Doha for peace talks with the United States, although the Haqqani network was not a direct interlocutor in those talks.

In addition, he was understood to be the group's main contact person for pro-Taliban elements in Pakistan, and was frequently seen moving around in Islamabad.

According to local residents, some family members of Nasiruddin Haqqani had been living in the Shahpur area on Islamabad's eastern outskirts for well over four years.

He was apparently using this base to organise financial and logistical support for his group and the Afghan Taliban.

So there were a number of groups who could have wanted to see him dead.

Fundraiser

Analysts believe his assassination has dealt a blow to the group's fundraising activities, because they think Nasiruddin was the only Haqqani free to exploit his father's vast Middle Eastern contacts. The others are either dead, or engaged in operational matters.

Some quarters also suggest he was Islamabad's main link to the TTP leadership in its recent peace overtures to that group.

A boy points to bullet holes in the wall of the bakery where Haqqani was shot

For these circles, the obvious suspects behind his killing would be either the Americans or the Afghans.

But others point to growing unease within the wider Taliban community in the North Waziristan sanctuary as the time for Nato's drawdown in Afghanistan gets nearer.

This unease is partly due to a fluid situation in Pakistan, where the political and military establishments are putting up a half-hearted battle against some right-wing politicians who appear bent on exploiting the anti-American feelings in the country to push it into international isolation.

Tribal sources say there is a clear split within the TTP, with some ethnic Mehsud commanders accusing the Haqqanis of toeing the Pakistani line.

The Haqqanis have also faced opposition from some Punjabi Taliban groups that were initially hosted and feted by them but have now sunk their own roots in the area and consider the Haqqanis to be as foreign to Waziristan as they are themselves.

Analysts feel 10 years after it was created, the Waziristan sanctuary is readying for change, with dozens of groups realigning amid shifts in relations and tactical priorities concerning Afghanistan, Pakistan and India.

For a while, there may be no clear friends or enemies in the area, they say.