Sri Lanka rights abuse allegations divide Commonwealth

- Published

Sri Lanka's president says the killings ended with the Tamil Tigers' defeat in 2009

The heads of government of the 53 nations of the Commonwealth come together every two years for a summit. This time, several have decided to stay away, to boycott the gathering in Sri Lanka.

The prime ministers of Canada, India and Mauritius say they cannot take part. Their basic complaint: Sri Lanka's President, Mahinda Rajapaksa, should not have been allowed to host the Commonwealth and then take over for the next two years as chairperson of an organisation committed to values of democracy and human rights which he is accused of flouting.

Other leaders are still coming, despite pressure on them to join the boycott.

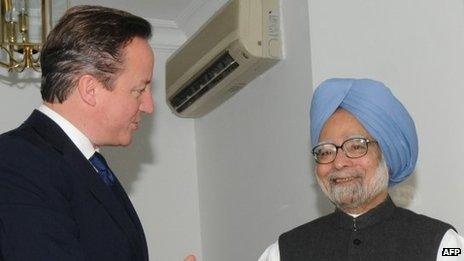

So Britain's Prime Minister, David Cameron, has flown in from neighbouring India, although his counterpart, India's Manmohan Singh, has pulled out. Mr Cameron says it's better to engage and ask tough questions rather than risk making the Commonwealth irrelevant as an organisation.

The case against Sri Lanka's government stems partly from allegations against the security forces of war crimes, including the killing of civilians, rape and sexual violence against women, particularly during the final months in 2009 of a civil war against Tamil separatists.

India's Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, has boycotted the summit in Sri Lanka

Critics also say there is considerable evidence of abuses both then and more recently, including the abduction or "disappearance" of opponents and the murder of journalists.

The government in Colombo rejects all these allegations, a denial repeated to me in a BBC interview by the country's minister of mass media and information, as Commonwealth leaders arrived in the country.

Test of will

"We wanted zero civilian casualties," said the minister, Keheliya Rambukwella, who is the government's spokesman. He added that it was well documented that the Tamil Tigers or LTTE, whom he called "terrorists", "used civilians as human shields".

The minister also rejected demands from Britain's prime minister. David Cameron is calling for an end to the intimidation of journalists and human rights defenders, action to stamp out torture, demilitarisation of the north and reconciliation between communities.

Mr Cameron says there needs to be a thorough investigation into alleged war crimes, and that if it does not happen rapidly, then an international independent investigation will be needed.

The Sri Lankan government accuses him of colonialism, of trying to dictate to a sovereign nation and of abusing his invitation to come to Colombo to discuss the issues on the formal agenda of this summit.

A Tamil girl whose father disappeared during the Sri Lankan civil war

But that agenda includes debate over what should replace the United Nations Millennium Development Goals when they expire in 2015.

That may allow any leader in the room to raise a whole host of human rights concerns, precisely because they are central to many people's belief that you cannot eradicate poverty without at the same time upholding rights, including the freedom to make political choices and freedom of speech.

Some people ask whether or not anyone would notice if the Commonwealth disappeared.

Supporters argue its achievements are often ignored. They point to a strong set of rules on democracy and elections: Commonwealth observer missions often play a significant role in limiting or preventing ballot-rigging.

Military takeovers are punished. Thirty years ago many Commonwealth countries were ruled by men in uniform. Not any more.

The Commonwealth is also much more than a club of political leaders. Its grassroots organisations, bringing together civil society groups around the globe, or professional associations exchanging best practice, or promoting trade are often more effective than gatherings of the political elite.

Small states also value the collective political weight they can sometimes exert via the Commonwealth in a world where their voices might otherwise be drowned out.

Critics, on the other hand, assemble lists of Commonwealth failings. Many have to do with promises made by leaders and then broken. Other charges involve rules which are not rigorously enforced.

The current controversy over the decision to meet in Colombo is seized on by the critics as further evidence the Commonwealth is all too flexible when it comes to sticking to its principles.

This year's new Commonwealth Charter commits leaders to uphold these principles. So this summit will be seen by many as a test of the Commonwealth's real commitment to values and a test of its collective will.

- Published14 November 2013

- Published13 November 2013

- Published9 November 2013